ALENKA V ŘÍŠI DIVŮ

12

CHAPTER XII.

ALENČINO SVĚDECTVÍ

Alice's Evidence

"ZDE!" zvolala Alenka. Úplnězapomněla ve vzrušení okamžiku, o kolik vyrostla za posledních několik chvil, a vyskočila s takovým spěchem, že okrajem své sukénky převrhla. lavici porotcůa vysypala je všechny na hlavy pod nimi shromážděného obecenstva; a tu uzřeli ubozí porotci zmítajíce sebou a velmi jí připomínajíce skleněnou nádrž se zlatými rybkami, kterou náhodou převrhla minulého týdne.

'Here!' cried Alice, quite forgetting in the flurry of the moment how large she had grown in the last few minutes, and she jumped up in such a hurry that she tipped over the jury-box with the edge of her skirt, upsetting all the jurymen on to the heads of the crowd below, and there they lay sprawling about, reminding her very much of a globe of goldfish she had accidentally upset the week before.

"Ó, tisíckrát prosím za odpuštění!" vykřikla tónem velkého zděšení, a začala milé porotce sbírat, jak jen rychle dovedla, neboťnehoda se zlatými rybkami jí dosud vězela v hlavěa ona se nejasnějaksi domnívala, že nesesbírá-li je ihned a neposadí zpět, kam patří, určitězahynou.

'Oh, I BEG your pardon!' she exclaimed in a tone of great dismay, and began picking them up again as quickly as she could, for the accident of the goldfish kept running in her head, and she had a vague sort of idea that they must be collected at once and put back into the jury-box, or they would die.

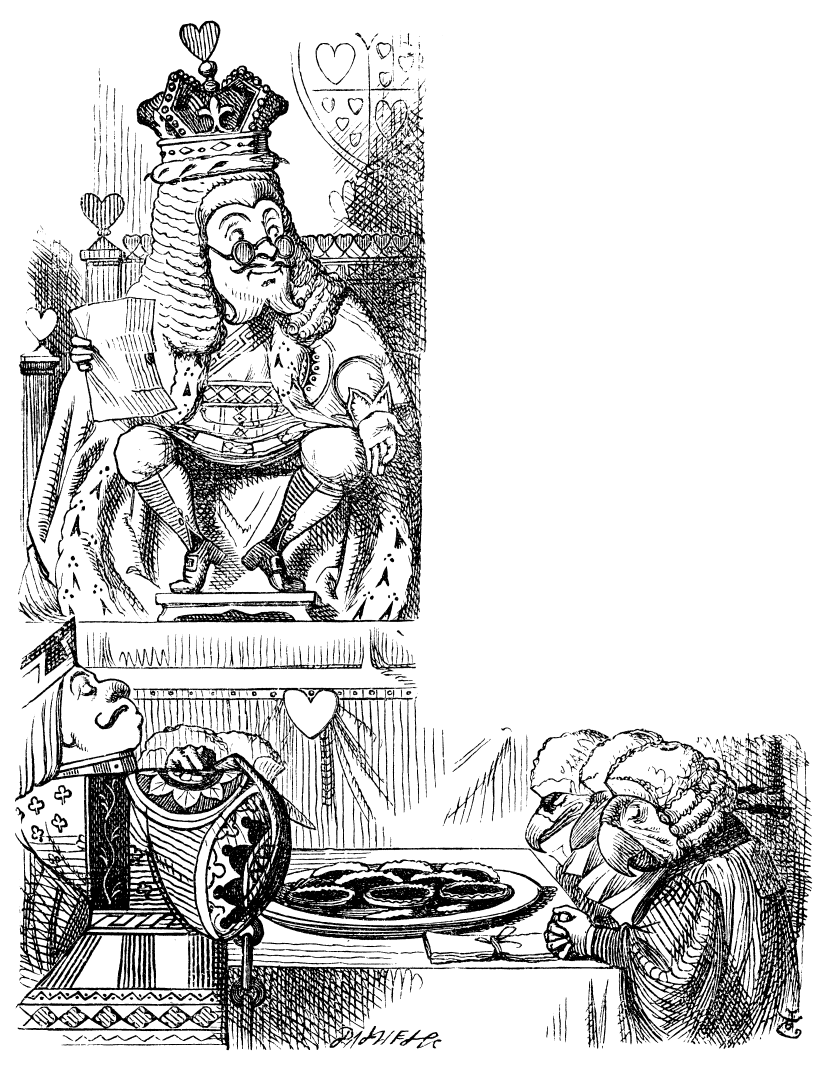

"V líčení se nemůže pokračovat," řekl Král velmi vážným hlasem, "dokud nebudou všichni porotci zpátky řádněna svých místech - ale všichni," opakoval s velkým důrazem, pohlížeje přísněna Alenku.

'The trial cannot proceed,' said the King in a very grave voice, 'until all the jurymen are back in their proper places—ALL,' he repeated with great emphasis, looking hard at Alice as he said do.

Alenka se podívala na lavici porotcůa viděla, že ve spěchu posadila ještěrku Vaňka hlavou dolů, a ten, ubožák, nemoha se pohnouti, smutněmával svým dlouhým ocáskem. Ihned ho uchopila a posadila hlavou vzhůru; "ne, že na tom mnoho záleží," řekla si k sobě; "myslím, že je nám tu při tomto líčení stejněplatný hlavou vzhůru jako vzhůru nohama."

Alice looked at the jury-box, and saw that, in her haste, she had put the Lizard in head downwards, and the poor little thing was waving its tail about in a melancholy way, being quite unable to move. She soon got it out again, and put it right; 'not that it signifies much,' she said to herself; 'I should think it would be QUITE as much use in the trial one way up as the other.'

Jakmile se porotci trochu vzpamatovali z leknutí, způsobeného touto nehodou, a jakmile se nalezly jejich tabulky a kamínky a byly jim vráceny, dali se pilnědo práce a začali popisovat historii celé příhody, všichni mimo Vaňka, jenž se zdál příliš zmožen, než aby mohl dělati něco jiného, nežli seděti s otevřenou hubou a dívati se do stropu soudní síně.

As soon as the jury had a little recovered from the shock of being upset, and their slates and pencils had been found and handed back to them, they set to work very diligently to write out a history of the accident, all except the Lizard, who seemed too much overcome to do anything but sit with its mouth open, gazing up into the roof of the court.

"Co víte o celé věci?" otázal se Král Alenky.

'What do you know about this business?' the King said to Alice.

"Nic," řekla Alenka.

'Nothing,' said Alice.

"Vůbec nic?" naléhal Král.

'Nothing WHATEVER?' persisted the King.

"Vůbec nic," řekla Alenka.

'Nothing whatever,' said Alice.

"To je velmi důležité," řekl Král, obraceje se k porotě. Porotci to zrovna začínali zapisovat na své tabulky, když Krále přerušil Bílý Králík: "Vaše Veličenstvo chtělo ovšem říci ,nedůležité`," řekl velmi uctivým tónem, ale přitom se mračil a dělal na Krále obličejem významné posuňky.

'That's very important,' the King said, turning to the jury. They were just beginning to write this down on their slates, when the White Rabbit interrupted: 'UNimportant, your Majesty means, of course,' he said in a very respectful tone, but frowning and making faces at him as he spoke.

"Ovšem, nedůležité, jsem chtěl říci," pravil spěšné Král a pokračoval polohlasem k sobě "důležité - nedůležité - nedůležité - důležité -" jako by uvažoval, které z obou slov zní lépe.

'UNimportant, of course, I meant,' the King hastily said, and went on to himself in an undertone, 'important—unimportant—unimportant—important—' as if he were trying which word sounded best.

Někteří porotci si zapsali "důležité" a někteří "nedůležité" , Alenka to viděla, ježto byla dosti blízko, aby mohla nahlédnouti do jejich tabulek; "ale naštěstí na tom vůbec nezáleží ", pomyslila si u sebe.

Some of the jury wrote it down 'important,' and some 'unimportant.' Alice could see this, as she was near enough to look over their slates; 'but it doesn't matter a bit,' she thought to herself.

V tom okamžiku Král, jenž už nějakou chvíli něco zapisoval do svého zápisníku, zvolal: "Ticho!" a přečetl ze své knihy: "Zákon čtyřicátý druhý: Veškeré osoby vyšší jedné míle musí opustit soudní síň."

At this moment the King, who had been for some time busily writing in his note-book, cackled out 'Silence!' and read out from his book, 'Rule Forty-two. ALL PERSONS MORE THAN A MILE HIGH TO LEAVE THE COURT.'

Všichni se dívali na Alenku.

Everybody looked at Alice.

"Já nejsem vyšší jedné míle," řekla Alenka.

'I'M not a mile high,' said Alice.

"Jste," řekl Král.

'You are,' said the King.

"Skoro celé dvěmíle," dodala Královna.

'Nearly two miles high,' added the Queen.

"Tak ať, ale já nepůjdu," řekla Alenka; "a mimo to není tožádný zákon: vy jste si to zrovna teďvymyslil."

'Well, I shan't go, at any rate,' said Alice: 'besides, that's not a regular rule: you invented it just now.'

"Je to nejstarší zákon v celé knize," řekl Král.

'It's the oldest rule in the book,' said the King.

"Pak by to mělo být Číslo Jedna," řekla Alenka.

'Then it ought to be Number One,' said Alice.

Král zbledl a spěšnězavřel svůj zápisník. "Uvažujte o svém výroku," řekl porotětichým, chvějícím se hlasem.

The King turned pale, and shut his note-book hastily. 'Consider your verdict,' he said to the jury, in a low, trembling voice.

"Ještěmusí přijít další důkazy o vině, ráčí-li Vaše Veličenstvo," řekl Bílý Králík, vyskočiv na nohy u velikém spěchu: "právěbyl nalezen tento papír."

'There's more evidence to come yet, please your Majesty,' said the White Rabbit, jumping up in a great hurry; 'this paper has just been picked up.'

"Co je v něm?" řekla Královna.

'What's in it?' said the Queen.

"Ještějsem ho neotevřel," řekl Bílý Králík, "ale zdá se, že je to dopis, který obžalovaný napsal pro - pro někoho."

'I haven't opened it yet,' said the White Rabbit, 'but it seems to be a letter, written by the prisoner to—to somebody.'

"Tak to jistěbude," řekl Král, "ledaže by ho byl psal pro nikoho, což, víte, není obvyklé."

'It must have been that,' said the King, 'unless it was written to nobody, which isn't usual, you know.'

"Komu je adresován?" otázal se jeden z porotců.

'Who is it directed to?' said one of the jurymen.

"Není vůbec adresován," řekl Bílý Králík, "a nic na něm ani není napsáno." Nato rozevřel papír a dodal: "A nakonec to není vůbec dopis: jsou to verše."

'It isn't directed at all,' said the White Rabbit; 'in fact, there's nothing written on the OUTSIDE.' He unfolded the paper as he spoke, and added 'It isn't a letter, after all: it's a set of verses.'

"Je to rukopis obžalovaného?" otázal se jiný z porotců.

'Are they in the prisoner's handwriting?' asked another of the jurymen.

"Nikoli, není," řekl Bílý Králík, "a to je na tom to nejpodivnější." Celá porota se dívala bezradně.

'No, they're not,' said the White Rabbit, 'and that's the queerest thing about it.' (The jury all looked puzzled.)

"Pak musil napodobit rukopis někoho jiného," řekl Král. Tváře porotcůse opět vyjasnily.

'He must have imitated somebody else's hand,' said the King. (The jury all brightened up again.)

"Ráčí-li Vaše Veličenstvo," řekl Srdcový Kluk, "já jsem to nepsal a oni nemohou dokázat, že jsem to psal: není to podepsáno."

'Please your Majesty,' said the Knave, 'I didn't write it, and they can't prove I did: there's no name signed at the end.'

"Jestliže jste to nepodepsal," řekl Král, "tak je to jenom tím horší. To jste jistězamýšlel nějakou špatnost, jinak byste sebyl podepsal jako poctivý člověk."

'If you didn't sign it,' said the King, 'that only makes the matter worse. You MUST have meant some mischief, or else you'd have signed your name like an honest man.'

Celá soudní síňpropukla v potlesk: byla toprvá opravdu chytrá věc, kterou Král toho dne řekl.

There was a general clapping of hands at this: it was the first really clever thing the King had said that day.

"To dokazuje jeho vinu," řekla Královna.

'That PROVES his guilt,' said the Queen.

"Nic takového to nedokazuje!" řekla Alenka. "Vždyťani nevíte, o čem ty verše jsou!"

'It proves nothing of the sort!' said Alice. 'Why, you don't even know what they're about!'

"Přečtěte je," řekl Král.

'Read them,' said the King.

Bílý Králík si nasadil brýle. "Kde mám začít, ráčí-li Vaše Veličenstvo?" otázal se.

The White Rabbit put on his spectacles. 'Where shall I begin, please your Majesty?' he asked.

"Začněte na začátku," řekl Král vážným hlasem, "a pokračujte, až přijdete ke konci, pak přestaňte."

'Begin at the beginning,' the King said gravely, 'and go on till you come to the end: then stop.'

Toto jsou verše, které Bílý Králík četl:

These were the verses the White Rabbit read:—

"On řekl mi, žes u ní byl

a mluvil o mněs ním;

Ona mi velmi měla v zlé,

že plavat neumím.

'They told me you had been to her,

And mentioned me to him:

She gave me a good character,

But said I could not swim.

On vzkázal, že jsem odešel,

(což, víme, pravda jest):

Půjdou-li věci takto dál,

kterou se dáte z cest?

He sent them word I had not gone

(We know it to be true):

If she should push the matter on,

What would become of you?

Já je dal jí, on zase jim,

vy pak je dali nám:

Ačvšechny byly nejdřív mé,

zas vrátily se k vám.

I gave her one, they gave him two,

You gave us three or more;

They all returned from him to you,

Though they were mine before.

Zapletu-li se já či on

v tu nepříjemnou věc,

tu doufáme, že vrátíte

jim volnost nakonec.

If I or she should chance to be

Involved in this affair,

He trusts to you to set them free,

Exactly as we were.

Já domníval se, že jste byl

(než na ni záchvat pad)

překážkou mezi ním a mnou,

a jí a námi snad.

My notion was that you had been

(Before she had this fit)

An obstacle that came between

Him, and ourselves, and it.

Jen neprozraď; že nade vše

je ony měly rády;

to musí zůstat tajemstvím

jen mezi kamarády."

Don't let him know she liked them best,

For this must ever be

A secret, kept from all the rest,

Between yourself and me.'

"To je nejdůležitější výpověď, kterou jsme dosud slyšeli," 'řekl Král, mna si ruce; "tak teď aťtedy porota - -"

'That's the most important piece of evidence we've heard yet,' said the King, rubbing his hands; 'so now let the jury—'

"Dovede-li. to kterýkoli z nich vysvětliti," řekla Alenka (v několika posledních minutách vyrostla již do takové velikosti, že se ani trochu nebála Krále přerušit), "dám mu pětník. Já nevěřím, že je ve všech těch verších nejmenší špetka smyslu."

'If any one of them can explain it,' said Alice, (she had grown so large in the last few minutes that she wasn't a bit afraid of interrupting him,) 'I'll give him sixpence. I don't believe there's an atom of meaning in it.'

Všichni porotci si zapisovali na tabulky: "Ona nevěří, že je ve všech těch verších nejmenší špetka smyslu", ale žádný se nepokusil verše vysvětlit.

The jury all wrote down on their slates, 'SHE doesn't believe there's an atom of meaning in it,' but none of them attempted to explain the paper.

"Není-li v nich žádného smyslu," řekl Král, "pak nás to ušetří velké spousty nesnází, víte, jelikož jej nepotřebujeme hledat. A přece, nevím - nevím," pokračoval, rozprostíraje si verše na kolena a nahlížeje do nich jedním okem, "zdá se mi, že v nich nakonec přece jen vidím jakýsi smysl. ,-- že plavat neumím --`, vy neumíte plavat, že ne?" dodal, obraceje se k Srdcovému Klukovi.

'If there's no meaning in it,' said the King, 'that saves a world of trouble, you know, as we needn't try to find any. And yet I don't know,' he went on, spreading out the verses on his knee, and looking at them with one eye; 'I seem to see some meaning in them, after all. "—SAID I COULD NOT SWIM—" you can't swim, can you?' he added, turning to the Knave.

Srdcový Kluk smutnězavrtěl hlavou. "Vypadám na to?" řekl. (Což opravdu nevypadal, jsa jen z papíru.)

The Knave shook his head sadly. 'Do I look like it?' he said. (Which he certainly did NOT, being made entirely of cardboard.)

"Tak to by tak dalece bylo v pořádku," řekl Král a tlumeněsi začal verše pro sebe přeříkávat: " ,-což, víme, pravda jest` - to se ovšemtýká poroty - ,já je dal jí, on zase jim` ! no tuto máme, zde říká, co s koláči udělal, víte - -"

'All right, so far,' said the King, and he went on muttering over the verses to himself: '"WE KNOW IT TO BE TRUE—" that's the jury, of course—"I GAVE HER ONE, THEY GAVE HIM TWO—" why, that must be what he did with the tarts, you know—'

"Ale dál stojí - ,zas vrátily se k vám`," řekla Alenka.

'But, it goes on "THEY ALL RETURNED FROM HIM TO YOU,"' said Alice.

"Nu, a tuhle jsou!" zvolal Král vítězoslavně, ukazuje na mísu koláčůna stole. "Nic nemůže být jasnějšího, než je tohle. A pak dál - ,- než na ni záchvat pad -` na vás, má drahá, nikdy, myslím, nepadl záchvat?" řekl, obraceje se ke Královně.

'Why, there they are!' said the King triumphantly, pointing to the tarts on the table. 'Nothing can be clearer than THAT. Then again—"BEFORE SHE HAD THIS FIT—" you never had fits, my dear, I think?' he said to the Queen.

"Nikdy!" vykřikla Královna zuřivěa hodila přitom kalamářna Vaňka. Nebohý malý Vaněk byl již zanechal psaní na tabulce prstem, shledav, že to nezanechává žádných stop; teďvšak opět začal horlivěpsát, užívaje k tomu inkoustu, který mu tekl potůčky po tváři.

'Never!' said the Queen furiously, throwing an inkstand at the Lizard as she spoke. (The unfortunate little Bill had left off writing on his slate with one finger, as he found it made no mark; but he now hastily began again, using the ink, that was trickling down his face, as long as it lasted.)

"Pak vám ta slova nepadnou," řekl Král, rozhlížeje se kolem sebe s úsměvem. V soudní síni však bylo mrtvé ticho.

'Then the words don't FIT you,' said the King, looking round the court with a smile. There was a dead silence.

"To je slovní hříčka!" dodal Král uraženým hlasem, a všichni se horlivědali do smíchu. "Nechťporota uvažuje o svém výroku," řekl Král, toho dne už asi po dvacáté.

'It's a pun!' the King added in an offended tone, and everybody laughed, 'Let the jury consider their verdict,' the King said, for about the twentieth time that day.

"Ne, ne!" zvolala Královna. "Rozsudek napřed - výrok poroty potom."

'No, no!' said the Queen. 'Sentence first—verdict afterwards.'

"Nesmysl!" řekla Alenka hlasitě. "To je nápad, chtít rozsudek před výrokem poroty!"

'Stuff and nonsense!' said Alice loudly. 'The idea of having the sentence first!'

"Vy buďte ticho!" vykřikla Královna, zrudnuvši do tmava.

'Hold your tongue!' said the Queen, turning purple.

"To nebudu!" řekla Alenka.

'I won't!' said Alice.

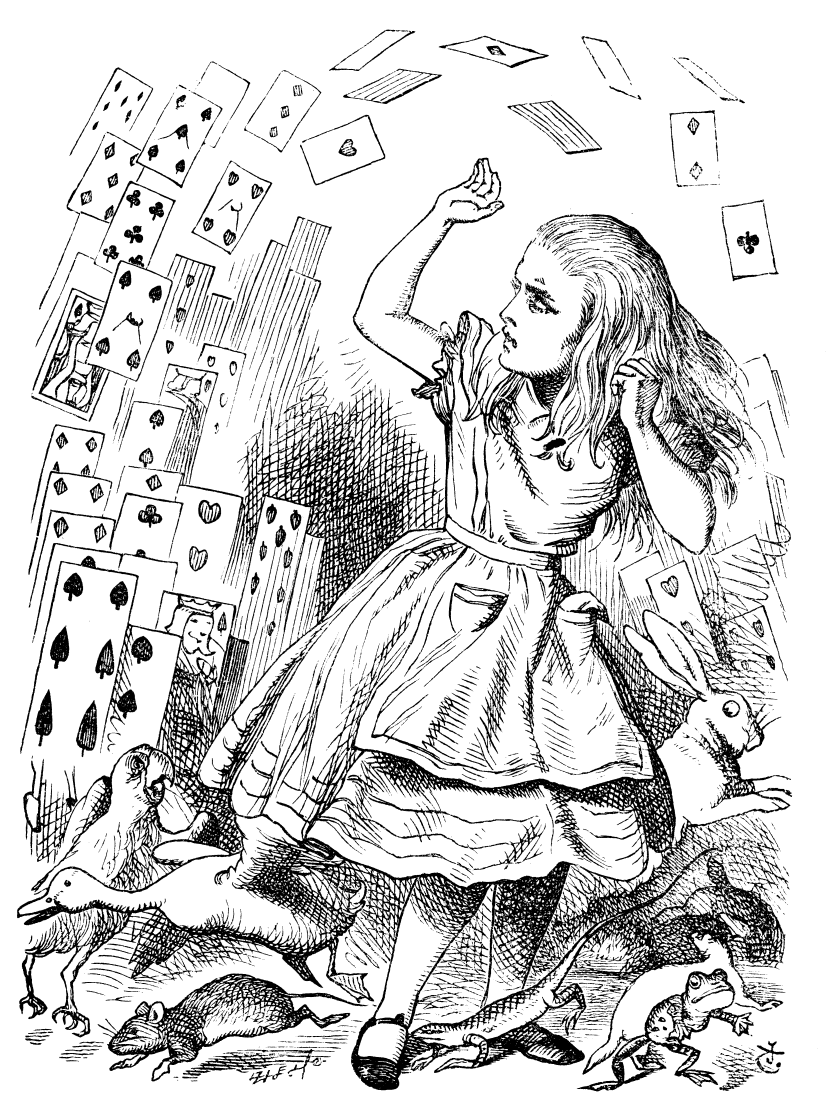

"Srazte jí hlavu!" ječela královna pronikavým hlasem. Nikdo se však nepohnul.

'Off with her head!' the Queen shouted at the top of her voice. Nobody moved.

"Kdo si z vás bude něco dělat!" řekla Alenka, která již tou dobou byla vyrostla do své přirozené velikosti. "Vždyťjste jen pouhá hromádka karet!"

'Who cares for you?' said Alice, (she had grown to her full size by this time.) 'You're nothing but a pack of cards!'

Sotva to dořekla, vznesla se celá hromádka do vzduchu a sesypala se na ni; Alenka vykřikla, napůl uleknutím a napůl hněvem, a jak se je pokoušela odraziti shledala, že leží na břehu řeky, hlavu položenu v klíněsvé sestry, která jí z tváře zlehka odmetala suché listí, jež na ni spadalo ze stromů.

At this the whole pack rose up into the air, and came flying down upon her: she gave a little scream, half of fright and half of anger, and tried to beat them off, and found herself lying on the bank, with her head in the lap of her sister, who was gently brushing away some dead leaves that had fluttered down from the trees upon her face.

"Probuďse, drahá Alenko," řekla sestra. "Jak jsi to dlouho spala."

'Wake up, Alice dear!' said her sister; 'Why, what a long sleep you've had!'

"Ó, měla jsem takový divný sen!" řekla Alenka a vyprávěla, jak nejlépe si je dovedla upamatovati, všechna ta podivná dobrodružství, o nichž jste právě četli; a když ukončila, políbila ji sestra a řekla: "To byl opravdu podivný sen, má drahá; ale teďpospěš a utíkej k svačině, je už hodněpozdě."

'Oh, I've had such a curious dream!' said Alice, and she told her sister, as well as she could remember them, all these strange Adventures of hers that you have just been reading about; and when she had finished, her sister kissed her, and said, 'It WAS a curious dream, dear, certainly: but now run in to your tea; it's getting late.' So Alice got up and ran off, thinking while she ran, as well she might, what a wonderful dream it had been.

Alenka tedy vstala a odběhla, přemýšlejíc cestou, jaký to byl podivuhodný sen. Její sestra však zůstala seděti, opírajíc hlavu o ruku, pozorujíc zapadající slunce a myslíc na malou Alenku a její podivuhodná dobrodružství, až sama upadla v jakési snění, a toto byl její sen:

But her sister sat still just as she left her, leaning her head on her hand, watching the setting sun, and thinking of little Alice and all her wonderful Adventures, till she too began dreaming after a fashion, and this was her dream:—

Nejprve snila o malé Alence samotné a poznovu jí Alenčiny drobné ruce objímaly kolena a Alenčiny jasné oči vzhlížely do jejích očí - znovu slyšela její hlas a viděla podivné pohození hlavou, jímž se zbavovala vlásků, které si nechtěly dát říci a padaly jí do očí - a jak mu tak pozorně naslouchala nebo zdála se naslouchati, vše kolem ní oživlo podivuhodnými stvořeními Alenčina snu.

First, she dreamed of little Alice herself, and once again the tiny hands were clasped upon her knee, and the bright eager eyes were looking up into hers—she could hear the very tones of her voice, and see that queer little toss of her head to keep back the wandering hair that WOULD always get into her eyes—and still as she listened, or seemed to listen, the whole place around her became alive with the strange creatures of her little sister's dream.

U nohou jí zašustěla dlouhá tráva pod spěšnými kroky Bílého Králíka - v nedalekém rybníčku šplouchala utíkající ulekaná myška - slyšela zvonění talířůa šálkůnekonečné svačiny Zajíce Březňáka a jeho přátel, i pronikavý hlas Královny, odsuzující nešťastné její hosty k smrti - znovu kýchalo děťátko-vepřík na Vévodčiněklíněza zvuku rozbíjených talířůa mís znovu byl vzduch pln skřeku Gryfona, skřípání ještěrčina kamínku o tabulku, dušeného sténání potlačovaných morčat a do toho všeho se mísilo vzdálené vzlykání nešťastné Falešné Želvy.

The long grass rustled at her feet as the White Rabbit hurried by—the frightened Mouse splashed his way through the neighbouring pool—she could hear the rattle of the teacups as the March Hare and his friends shared their never-ending meal, and the shrill voice of the Queen ordering off her unfortunate guests to execution—once more the pig-baby was sneezing on the Duchess's knee, while plates and dishes crashed around it—once more the shriek of the Gryphon, the squeaking of the Lizard's slate-pencil, and the choking of the suppressed guinea-pigs, filled the air, mixed up with the distant sobs of the miserable Mock Turtle.

Tak seděla se zavřenýma očima a napolo věřila, že se sama octla v podzemní říši divů, ačkoli věděla, že nepotřebuje než oči otevřít a vše se promění v šedou skutečnost: tráva bude šustět pouze dotykem větru - rybníček se bude čeřit vlnícím se rákosím - zvonění šálků čajové společnosti se změní v pouhé cinkání zvonkůpasoucích se ovcí a ostré Královniny výkřiky v pokřikování pasáčka - kýchání dítěte, skřek Gryfonův a všechny ty ostatní podivné zvuky, věděla, se změní ve zmatený hluk nádvoří venkovského statku, a bučení krav v dálce nastoupí namísto těžkého vzlykání Falešné Želvy.

So she sat on, with closed eyes, and half believed herself in Wonderland, though she knew she had but to open them again, and all would change to dull reality—the grass would be only rustling in the wind, and the pool rippling to the waving of the reeds—the rattling teacups would change to tinkling sheep-bells, and the Queen's shrill cries to the voice of the shepherd boy—and the sneeze of the baby, the shriek of the Gryphon, and all the other queer noises, would change (she knew) to the confused clamour of the busy farm-yard—while the lowing of the cattle in the distance would take the place of the Mock Turtle's heavy sobs.

A nakonec si představila, jak tato její malá sestřička bude v pozdější doběsama dospělou ženou; a jak si i ve zralém věku zachová prosté a milující srdce svého dětství a jak kolem sebe shromáždí jiné malé děti a rozzáří jim oči mnohým podivným vyprávěním, snad také vyprávěním svého dávného snu o podzemní říši divů; a jak s nimi bude cítit ve všech jejich prostých zármutcích a nacházeti radost v jejich prostých radostech, vzpomínajíc si na vlastní své dětství a šťastné dny tohoto léta.

Lastly, she pictured to herself how this same little sister of hers would, in the after-time, be herself a grown woman; and how she would keep, through all her riper years, the simple and loving heart of her childhood: and how she would gather about her other little children, and make THEIR eyes bright and eager with many a strange tale, perhaps even with the dream of Wonderland of long ago: and how she would feel with all their simple sorrows, and find a pleasure in all their simple joys, remembering her own child-life, and the happy summer days.

THE END

Audio from LibreVox.org