La Aventuroj de Alicio en Mirlando

Ĉapitro 2

CHAPTER II.

La Lageto farita el Larmoj

The Pool of Tears

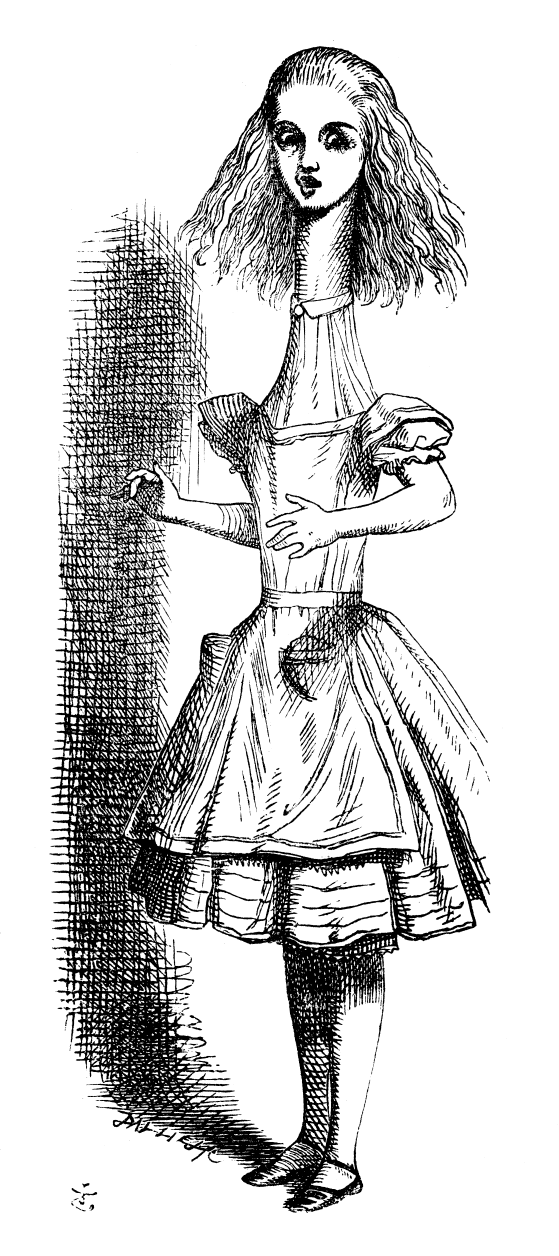

“Neniam mi spertis tiaĵo,” ekkriis Alicio, (pro eksciteco ŝi eĉ forgesis la akuzativon). “Jen mi plilongiĝas teleskope, kiel la plej granda teleskopo en la tuta mondo. Adiaŭ, piedetoj miaj!” (Kiam ŝi direktis la rigardojn al la piedoj, pro la plilongiĝo ili jam fariĝis tute malproksimaj, kaj apenaŭ ŝi povis vidi ilin.)

“Ho, vi kompatinduloj! kiu morgaŭ vestos al vi la ŝtrumpojn kaj ŝuojn? Kompreneble ne mi; mi estos tro malproksime por okupi min pri vi; vi devos klopodi por vi mem. Tamen estas necese komplezi ilin; ĉar se ili ofendiĝos, ili eble rifuzos marŝi laŭ mia volo. Mi do en la kristnaska tempo donacos al ili paron da novaj botoj.”

'Curiouser and curiouser!' cried Alice (she was so much surprised, that for the moment she quite forgot how to speak good English); 'now I'm opening out like the largest telescope that ever was! Good-bye, feet!' (for when she looked down at her feet, they seemed to be almost out of sight, they were getting so far off). 'Oh, my poor little feet, I wonder who will put on your shoes and stockings for you now, dears? I'm sure I shan't be able! I shall be a great deal too far off to trouble myself about you: you must manage the best way you can;—but I must be kind to them,' thought Alice, 'or perhaps they won't walk the way I want to go! Let me see: I'll give them a new pair of boots every Christmas.'

Ŝi eĉ elpensadis detale kiel ŝi faros la necesajn aranĝojn. “Mi pagos al la portisto por liveri ilin, kaj kiel stranga tio ŝajnos, sendi donacon al siaj piedoj! Ankaŭ la adreso estos tre stranga:

And she went on planning to herself how she would manage it. 'They must go by the carrier,' she thought; 'and how funny it'll seem, sending presents to one's own feet! And how odd the directions will look!

Al lia Moŝto la Dekstra Piedo Alicia,

sur la Tapiŝeto

apud Fajrgardilo

(Kun amsalut’ de Alicio).

ALICE'S RIGHT FOOT, ESQ.

HEARTHRUG,

NEAR THE FENDER,

(WITH ALICE'S LOVE).

Ho, kian sensencaĵon mi parolas!”

Oh dear, what nonsense I'm talking!'

En tiu momento ŝia kapo ekpremis la plafonon. Do, sen plua prokrasto ŝi levis la oran ŝlosileton kaj rapidis al la ĝardenpordeto. Sed havante la altecon de tri metroj, ŝi apenaŭ povis, kuŝante sur la planko, rigardi per unu okulo en la ĝardenon, kaj la tasko eniĝi en ĝin fariĝis ja pli ol iam utopia. Ŝi sidiĝis kaj denove ekploris.

Just then her head struck against the roof of the hall: in fact she was now more than nine feet high, and she at once took up the little golden key and hurried off to the garden door.

Poor Alice! It was as much as she could do, lying down on one side, to look through into the garden with one eye; but to get through was more hopeless than ever: she sat down and began to cry again.

“Vi devas honti,” ŝi diris al si, “vi granda bubino!” (ŝi certe ne eraris pri la lastaj du vortoj) “multe tro granda vi estas por plorkrii, vi tuj ĉesu!” Malgraŭ tiu akra sinriproĉo, ŝi ne ĉesis la ploradon, ĝis ŝi faligis kelkajn hektolitrojn da larmegoj, kaj etendis sin ĉirkaŭ ŝi larmlageto profunda je dek centimetroj kaj kovranta preskaŭ la tutan plankon de la halo.

'You ought to be ashamed of yourself,' said Alice, 'a great girl like you,' (she might well say this), 'to go on crying in this way! Stop this moment, I tell you!' But she went on all the same, shedding gallons of tears, until there was a large pool all round her, about four inches deep and reaching half down the hall.

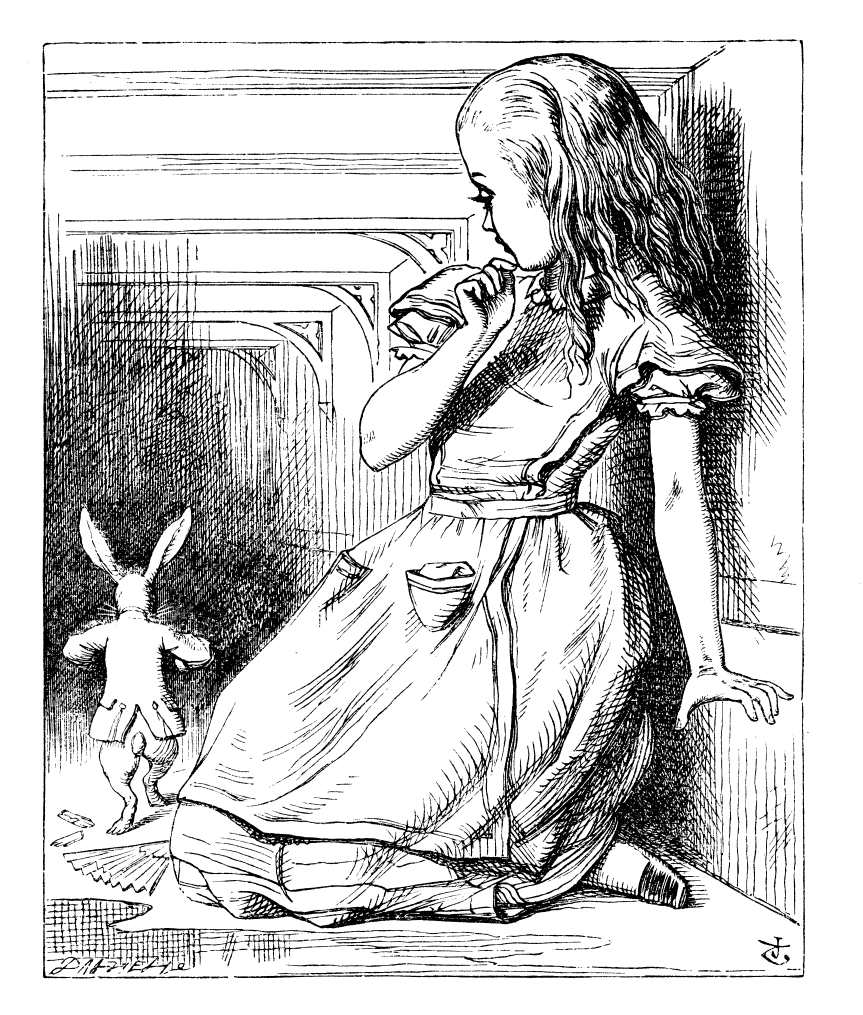

Post ne longa tempo ŝi aŭdis ian piedfrapetadon, kaj vigle forviŝis la larmojn por esplori kiu venas. Jen reaperis la Blanka Kuniklo lukse vestita, havante en unu mano paron da blankaj gantoj, kaj en la alia grandan ventumilon. Jen li alvenis, trotrapide, kaj murmuris al si: “Ho, la Dukino! Se mi igos ŝin atendi, ŝi tute furioziĝos!”

Ĉar Alicio jam fariĝis preskaŭ senespera, ŝi estis preta peti helpon de kiu ajn. Do, kiam la Kuniklo sufiĉe apudiĝis, ŝi ekparolis per tre mallaŭta timplena voĉo: “Se al vi plaĉos, Sinjoro:—”

La Kuniklo forte eksaltis, lasis fali gantojn kaj ventumilon, kaj per ĉiuj fortoj ekforkuregis en la mallumon!

After a time she heard a little pattering of feet in the distance, and she hastily dried her eyes to see what was coming. It was the White Rabbit returning, splendidly dressed, with a pair of white kid gloves in one hand and a large fan in the other: he came trotting along in a great hurry, muttering to himself as he came, 'Oh! the Duchess, the Duchess! Oh! won't she be savage if I've kept her waiting!' Alice felt so desperate that she was ready to ask help of any one; so, when the Rabbit came near her, she began, in a low, timid voice, 'If you please, sir—' The Rabbit started violently, dropped the white kid gloves and the fan, and skurried away into the darkness as hard as he could go.

Alicio levis la gantojn kaj ventumilon, kaj ĉar estis en la halo tre varme, ŝi longadaŭre ventumadis sin kaj samtempe babiladis:—

“Hieraŭ ĉio okazis laŭrutine, sed hodiaŭ ja ĉio estas stranga! Ĉu dum la nokto mi ŝanĝiĝis? mi esploru tion. Ĉu vere mi estis sama kiam mi leviĝis hodiaŭ matene? Mi kvazaŭ memoras ke mi sentis min iom ŝanĝiĝinta. Sed se mi ne estas sama, jen alia demando; kiu mi estas? Jen granda enigmo!” Kaj ŝi kategorie pripensis ĉiujn samaĝajn knabinetojn kiujn ŝi konas, por certiĝi ĉu ŝi ŝanĝiĝis en iun el ili.

Alice took up the fan and gloves, and, as the hall was very hot, she kept fanning herself all the time she went on talking: 'Dear, dear! How queer everything is to-day! And yesterday things went on just as usual. I wonder if I've been changed in the night? Let me think: was I the same when I got up this morning? I almost think I can remember feeling a little different. But if I'm not the same, the next question is, Who in the world am I? Ah, THAT'S the great puzzle!' And she began thinking over all the children she knew that were of the same age as herself, to see if she could have been changed for any of them.

“Mi certe ne estas Ado, ĉar ŝia hararo falas sur la ŝultroj per longaj bukloj, kaj la mia estas tute ne bukla. Ankaŭ mi ne estas Mabelo, ĉar mi scias multe da lernaĵoj, kaj ŝi scias ja tre, tre malmulte. Ankaŭ ŝi estas si, kaj mi mi, kaj … ho, mi tute konfuziĝas! Mi provu ĉu mi ankoraŭ scias la jam longe konitajn faktojn. Por komenci: kvaroble kvin faras dekdu, kvaroble ses faras dektri, kvaroble sep faras…. Ho, tiamaniere neniam mi atingus dudek! Tamen la Multiplika Tabelo estas por mi indiferenta; mi ekzamenu min geografie. Londono estas ĉefurbo de Parizo, Parizo ĉefurbo de Romo, kaj Romo…. Ne, denove mi eraras, certege. Mi nepre ŝanĝiĝis en Mabelon. Mi penos deklami ‘Rigardu! Jen abelo vigla.’”

Kaj kruciginte la manojn sur la genuoj same kiel en la lernejo kiam ŝi ripetas parkeraĵojn, ŝi komencis tiun konatan poemon. Sed ŝia voĉo sonis raŭka kaj nepropra, kaj eĉ la vortoj ne tute similis la originalajn.

'I'm sure I'm not Ada,' she said, 'for her hair goes in such long ringlets, and mine doesn't go in ringlets at all; and I'm sure I can't be Mabel, for I know all sorts of things, and she, oh! she knows such a very little! Besides, SHE'S she, and I'm I, and—oh dear, how puzzling it all is! I'll try if I know all the things I used to know. Let me see: four times five is twelve, and four times six is thirteen, and four times seven is—oh dear! I shall never get to twenty at that rate! However, the Multiplication Table doesn't signify: let's try Geography. London is the capital of Paris, and Paris is the capital of Rome, and Rome—no, THAT'S all wrong, I'm certain! I must have been changed for Mabel! I'll try and say "How doth the little—"' and she crossed her hands on her lap as if she were saying lessons, and began to repeat it, but her voice sounded hoarse and strange, and the words did not come the same as they used to do:—

Rigardu! Jen la krokodil’!

La voston li netigas;

Ŝprucante akvon el la Nil’

La skvamojn li briligas.

'How doth the little crocodile

Improve his shining tail,

And pour the waters of the Nile

On every golden scale!

Senmova restas la buŝeg’,

Li ungojn kaŝas ruze;

Jen fiŝoj naĝas tra l’ kaveg’

Frapfermas li amuze.

'How cheerfully he seems to grin,

How neatly spread his claws,

And welcome little fishes in

With gently smiling jaws!'

“Jen certe ne la ĝustaj vortoj,” diris Alicio malĝoje, kaj denove la okuloj pleniĝis de larmoj, dum ŝi daŭrigis: “Do, mi nepre estas Mabelo malgraŭ ĉio; sekve mi devos loĝi en tiu ŝia mallarĝa maloportuna domaĉeto; mi havos neniun ŝatindan ludilon, kaj devos lerni sennombrajn lecionojn. Ne! Pri tio mi decidiĝis. Se mi estos Mabelo, mi restos ĉi tie, kaj neniom utilos ke oni demetu la kapon ĉe la enirejo al la tunelo kaj diru per karesa voĉo ‘Resupreniru, karulo.’ Mi nur rigardos supren kaj demandos ‘Kiu do mi estas? Vi certigu tion, kaj poste, se mi ŝatos esti tiu persono, mi konsentos supreniri. Se ne, mi restos ĉi tie, ĝis mi fariĝos iu alia.’ Sed ho ve! mi tre, tre volas ke oni venu. Jam tro longan tempon mi restas tie ĉi tutsola, kaj mi sopiras la hejmon.”

'I'm sure those are not the right words,' said poor Alice, and her eyes filled with tears again as she went on, 'I must be Mabel after all, and I shall have to go and live in that poky little house, and have next to no toys to play with, and oh! ever so many lessons to learn! No, I've made up my mind about it; if I'm Mabel, I'll stay down here! It'll be no use their putting their heads down and saying "Come up again, dear!" I shall only look up and say "Who am I then? Tell me that first, and then, if I like being that person, I'll come up: if not, I'll stay down here till I'm somebody else"—but, oh dear!' cried Alice, with a sudden burst of tears, 'I do wish they WOULD put their heads down! I am so VERY tired of being all alone here!'

Dirante tion ŝi okaze rigardis la manojn kaj rimarkis mirigite ke ŝi vestis—dum ŝi babilas—unu el la blankaj kapridfelaj gantoj de la Kuniklo.

“Kiel ajn mi faris tion?” pensis ŝi. “Mi ja denove malkreskas.”

Ŝi stariĝis, kaj irinte al la tablo por kompare mezuri sin, eltrovis ke nun ŝi havas proksimume sesdek centimetrojn da alteco, kaj ankoraŭ rapide malkreskas. Certiĝinte ke tion kaŭzas la ventumilo, ŝi tuj lasis ĝin fali, kaj per tio apenaŭ ŝi evitis la malagrablaĵon malkreski ĝis nulo.

As she said this she looked down at her hands, and was surprised to see that she had put on one of the Rabbit's little white kid gloves while she was talking. 'How CAN I have done that?' she thought. 'I must be growing small again.' She got up and went to the table to measure herself by it, and found that, as nearly as she could guess, she was now about two feet high, and was going on shrinking rapidly: she soon found out that the cause of this was the fan she was holding, and she dropped it hastily, just in time to avoid shrinking away altogether.

“Jen evito vere mirakla! Ĉar preskaŭ mi nuliĝis!” diris Alicio, iom timigita per la subita ŝanĝo, “tamen estas bona afero trovi sin ankoraŭ ekzistanta; kaj jam nun mi povas eniri la ĝardenon.” Ŝi do kuris avide al la pordeto; sed ho ve! ĝi refermiĝis, kaj jen la ora ŝlosileto kuŝis, kiel antaŭe, sur la tablo; kaj “la afero staras pli malprospere ol ĉiam,” ŝi plordiris, “ĉar neniam mi estis tiel absurde malgranda, estas ja ne tolereble.”

'That WAS a narrow escape!' said Alice, a good deal frightened at the sudden change, but very glad to find herself still in existence; 'and now for the garden!' and she ran with all speed back to the little door: but, alas! the little door was shut again, and the little golden key was lying on the glass table as before, 'and things are worse than ever,' thought the poor child, 'for I never was so small as this before, never! And I declare it's too bad, that it is!'

En la momento kiam ŝi diris tion, ŝia piedo glitis, kaj ŝi trovis sin plaŭde enfalinta en salan akvon. Subakviĝinte ĝis la mentono, ŝi unue supozis ke ŝi estas falinta en la maron, kaj ekpensis “en tiu okazo mi povos hejmiĝi vagonare.” (Alicio nur unufoje en la vivo forrestadis ĉe la marbordo, kaj el tiu sperto formis al si la konkludon ke, kien ajn oni irus sur la angla marbordo, oni trovus longan serion de banmaŝinoj en la maro, post ili kelke da infanoj kiuj per lignaj fosiloj fosas la sablon; malantaŭe, serion de apartamentaj domoj, kun, malantaŭ ĉio, stacidomo.) Tamen post nelonge ŝi sciiĝis ke ŝi estas en la lageto farita de la larmoj kiujn ŝi ploris estante trimetrulo.

As she said these words her foot slipped, and in another moment, splash! she was up to her chin in salt water. Her first idea was that she had somehow fallen into the sea, 'and in that case I can go back by railway,' she said to herself. (Alice had been to the seaside once in her life, and had come to the general conclusion, that wherever you go to on the English coast you find a number of bathing machines in the sea, some children digging in the sand with wooden spades, then a row of lodging houses, and behind them a railway station.) However, she soon made out that she was in the pool of tears which she had wept when she was nine feet high.

“Ho, se nur mi ne tiom plorus!” diris ŝi, ĉirkaŭnaĝante por trovi la bordon. “Pro tiuj larmoj mi nun eble suferos la punon droni en la larmoj mem. Tio estos tre, tre stranga, sed hodiaŭ ĉio ja estas stranga.”

'I wish I hadn't cried so much!' said Alice, as she swam about, trying to find her way out. 'I shall be punished for it now, I suppose, by being drowned in my own tears! That WILL be a queer thing, to be sure! However, everything is queer to-day.'

En tiu momento ŝi ekaŭdis ke io ne tre malproksime de ŝi ĉirkaŭbaraktas en la lageto, kaj ŝi naĝis en la direkto de la plaŭdado por esplori kio ĝi estas: unue ŝi supozis ke la besto nepre estos aŭ rosmaro aŭ hipopotamo; sed rememorante ke ŝi mem nun estas tre malgranda, ŝi fine konstatis ke ĝi estas nur muso englitinta en la akvon same kiel ŝi mem.

Just then she heard something splashing about in the pool a little way off, and she swam nearer to make out what it was: at first she thought it must be a walrus or hippopotamus, but then she remembered how small she was now, and she soon made out that it was only a mouse that had slipped in like herself.

“Ĉu eble utilus,” pensis Alicio, “alparoli ĉi tiun muson? Ĉio estas tiel neordinara ĉi tie, ke kredeble ĝi havas la kapablon paroli, kaj almenaŭ ne malutilos provi ĝin.” Do ŝi ekparolis per: “Ho muso, ĉu vi konas la elirejon el tiu ĉi lageto? Mi tre laciĝas, ho Muso, ĉirkaŭnaĝante en ĝi.” (Alicio kredis ke “Ho Muso” estas nepre prava formo por alparoli muson; ŝi neniam ĝis tiu tago alparolis muson, sed ŝi memoris el la latina lernolibro de sia frato la deklinacion: “Muso—de muso—al muso—muson—ho muso!“)

La Muso rigardis ŝin scivole, tamen diris nenion, sed faris signon al ŝi palpebrumante per unu okuleto.

'Would it be of any use, now,' thought Alice, 'to speak to this mouse? Everything is so out-of-the-way down here, that I should think very likely it can talk: at any rate, there's no harm in trying.' So she began: 'O Mouse, do you know the way out of this pool? I am very tired of swimming about here, O Mouse!' (Alice thought this must be the right way of speaking to a mouse: she had never done such a thing before, but she remembered having seen in her brother's Latin Grammar, 'A mouse—of a mouse—to a mouse—a mouse—O mouse!') The Mouse looked at her rather inquisitively, and seemed to her to wink with one of its little eyes, but it said nothing.

“Ĝi eble estas franca muso alveninta Anglujon kun Vilhelmo la Venkanto; sekve ĝi povas ne kompreni la anglan lingvon.” (Malgraŭ la fakto ke ŝi bone konis multe da historiaj nomoj kaj epizodoj, Alicio ne havis tre klarajn ideojn pri datoj!) Ŝi do rekomencis france, dirante “où est ma chatte?” (la unua frazo en ŝia lernolibro).

La Muso tuj eksaltis el la akvo, kaj ĝia tuta korpo timskuiĝis.

“Ho, pardonu! mi petegas,” ekkriis Alicio, timante ke ŝi vundis la sentojn al la kompatinda besto, “mi tute forgesis ke vi ne amas la katojn.”

'Perhaps it doesn't understand English,' thought Alice; 'I daresay it's a French mouse, come over with William the Conqueror.' (For, with all her knowledge of history, Alice had no very clear notion how long ago anything had happened.) So she began again: 'Ou est ma chatte?' which was the first sentence in her French lesson-book. The Mouse gave a sudden leap out of the water, and seemed to quiver all over with fright. 'Oh, I beg your pardon!' cried Alice hastily, afraid that she had hurt the poor animal's feelings. 'I quite forgot you didn't like cats.'

“Ne—amas—katojn,” diris ripete la Muso per pasia sibla voĉo. “Ĉu vi, se vi estus mi, amus la katojn?”

'Not like cats!' cried the Mouse, in a shrill, passionate voice. 'Would YOU like cats if you were me?'

“Nu, eble ne,” Alicio respondis per paciga tono, “sed ne koleriĝu. Malgraŭ ĉio, mi tre ŝatus montri al vi nian katon Dajna; vi nepre ekamus la katojn, se nur vi povus vidi ŝin. Ŝi estas la plej kara dorlotaĵo en tuta la mondo,”—Alicio malvigle sencele naĝetis dum ŝi parolis—“kaj tiel komforte ŝi murmuras apud la fajro lekante la piedojn kaj viŝante la vizaĝon; ankaŭ tiel bela molaĵo por dorloti sur la genuoj, ankaŭ tiel lerta muskaptisto—ho, pardonu,” denove ekkriis Alicio, ĉar la Muso elstarigis erinace la tutan felon; sekve ŝi estis certa ke ĝi tre profunde ofendiĝis, kaj ŝi rapidis aldoni: “Se estas al vi malagrable, ni ne plu parolu pri Dajna.”

'Well, perhaps not,' said Alice in a soothing tone: 'don't be angry about it. And yet I wish I could show you our cat Dinah: I think you'd take a fancy to cats if you could only see her. She is such a dear quiet thing,' Alice went on, half to herself, as she swam lazily about in the pool, 'and she sits purring so nicely by the fire, licking her paws and washing her face—and she is such a nice soft thing to nurse—and she's such a capital one for catching mice—oh, I beg your pardon!' cried Alice again, for this time the Mouse was bristling all over, and she felt certain it must be really offended. 'We won't talk about her any more if you'd rather not.'

“Ni ne plu!” ekkriis la Muso, kiu tremis ĝis la lasta vostharo. “Ĉu vi imagas ke mi volus priparoli tian temon? Ĉiam nia familio malamis la katojn kaj nun malamas, malamindaj malĝentilaj bestoj! Estonte vi jam neniam aŭdigu antaŭ mi eĉ la nomon kato!”

'We indeed!' cried the Mouse, who was trembling down to the end of his tail. 'As if I would talk on such a subject! Our family always HATED cats: nasty, low, vulgar things! Don't let me hear the name again!'

“Tion mi promesas tre volonte,” diris Alicio, kaj dume klopodis trovi alian paroltemon. “Ĉu vi … ĉu vi ŝatas … la hundojn?”

La Muso ne respondis. Sekve Alicio avide daŭrigis:—

“Proksime de nia domo loĝas bela, ĉarma, hundeto, kiun mi tre ŝatus ke vi vidu. Ĝi estas malgranda, helokula rathundo kun longa bukla brunhararo. Ĝi kapablas realporti la aĵojn forĵetitajn; ĝi petas manĝaĵon sidante sur la vosto, kaj havas aliajn ĉiuspecajn kapablojn; mi ne povas memori eĉ la duonon da ili. Ĝi apartenas al iu farmisto kiu diras ke pro ĝiaj kapabloj ĝi valoras mil spesmilojn.

Li certigas ke ĝi mortigas ĉiujn ratojn kaj … Ho, ve! ve! Denove mi ofendis ĝin.” Ĉar jen! la Muso naĝas for, for per ĉiuj fortoj, kun tia rapideco ke li faras irante tra la akvo grandan plaŭdbruon.

'I won't indeed!' said Alice, in a great hurry to change the subject of conversation. 'Are you—are you fond—of—of dogs?' The Mouse did not answer, so Alice went on eagerly: 'There is such a nice little dog near our house I should like to show you! A little bright-eyed terrier, you know, with oh, such long curly brown hair! And it'll fetch things when you throw them, and it'll sit up and beg for its dinner, and all sorts of things—I can't remember half of them—and it belongs to a farmer, you know, and he says it's so useful, it's worth a hundred pounds! He says it kills all the rats and—oh dear!' cried Alice in a sorrowful tone, 'I'm afraid I've offended it again!' For the Mouse was swimming away from her as hard as it could go, and making quite a commotion in the pool as it went.

Ŝi realvokis ĝin per sia plej dolĉa tono. “Vi kara Muso, revenu! mi petegas; nek katojn nek hundojn ni priparolos, se al vi ne plaĉos.” Aŭdinte tion, la Muso turnis sin malrapide kaj renaĝis al ŝi. Ĝia vizaĝo estis tre pala (pro kolero, pensis en si Alicio), kaj per mallaŭta tremanta voĉo ĝi diris: “Ni naĝu al la bordo, kaj poste mi rakontos al vi mian historion, por komprenigi pro kio mi malamas la katojn kaj hundojn.”

So she called softly after it, 'Mouse dear! Do come back again, and we won't talk about cats or dogs either, if you don't like them!' When the Mouse heard this, it turned round and swam slowly back to her: its face was quite pale (with passion, Alice thought), and it said in a low trembling voice, 'Let us get to the shore, and then I'll tell you my history, and you'll understand why it is I hate cats and dogs.'

Kaj certe estus malprudente plu prokrasti la elnaĝon, ĉar en la lageton jam enfalis tiom da birdoj kaj bestoj ke ili komencis premi sin reciproke. Jen Anaso naĝis kun Dodo, jen Loro kun Agleto, jen multe da aliaj strangaĵoj, birdbestoj kaj bestbirdoj. Unua naĝis Alicio; post ŝi sekvis la tuta birdbestaro. Post kelka tempo ĉiuj atingis la bordon kaj staris kune sur la tero, tre malsekaj.

It was high time to go, for the pool was getting quite crowded with the birds and animals that had fallen into it: there were a Duck and a Dodo, a Lory and an Eaglet, and several other curious creatures. Alice led the way, and the whole party swam to the shore.

Audio from LibreVox.org

Audio from LibreVox.org