La Aventuroj de Alicio en Mirlando

Ĉapitro 3

CHAPTER III.

Post stranga vetkuro sekvas stranga mus-tejlo

A Caucus-Race and a Long Tale

La kunvenintoj sur la bordo prezentis tre strangan aspekton. Jen birdoj kun plumoj malordigitaj, jen bestoj kun felo algluiĝinta al la korpo: ĉiuj estis akvogutantaj, malkomfortaj, malagrablaj.

They were indeed a queer-looking party that assembled on the bank—the birds with draggled feathers, the animals with their fur clinging close to them, and all dripping wet, cross, and uncomfortable.

Kompreneble la unua demando estis: kiamaniere resekiĝi? Ili interkonsiliĝis pri tio, kaj post kelke da minutoj ŝajnis al Alicio tute ordinara afero trovi sin babilanta kun ili kvazaŭ al personoj jam longe konataj. Ŝi havis longan argumentadon kun la Loro, kiu en la fino fariĝis malagrabla kaj volis diri nenion krom “mi estas la pli aĝa, kaj pro tio mi scias pli.” Ĉar Alicio rifuzis konsenti al tio, ne sciante kiom da jaroj li havas, kaj ĉar la Loro absolute rifuzis doni tiun sciigon, restis nenio plu direbla.

The first question of course was, how to get dry again: they had a consultation about this, and after a few minutes it seemed quite natural to Alice to find herself talking familiarly with them, as if she had known them all her life. Indeed, she had quite a long argument with the Lory, who at last turned sulky, and would only say, 'I am older than you, and must know better'; and this Alice would not allow without knowing how old it was, and, as the Lory positively refused to tell its age, there was no more to be said.

Fine la Muso, kiu ŝajne estis aŭtoritatulo, ekkriis: “Vi sidiĝu ĉiuj, kaj aŭskultu min. Mi tre baldaŭ igos vin sufiĉe sekaj!”

Ili do sidiĝis, ĉiuj en unu granda rondo, kun la Muso en la centro.

Alicio fikse kaj atente rigardadis la Muson, ĉar ŝi havis fortan antaŭsenton, ke ŝi nepre suferos malvarmumon, se ŝi ne baldaŭ resekiĝos.

At last the Mouse, who seemed to be a person of authority among them, called out, 'Sit down, all of you, and listen to me! I'LL soon make you dry enough!' They all sat down at once, in a large ring, with the Mouse in the middle. Alice kept her eyes anxiously fixed on it, for she felt sure she would catch a bad cold if she did not get dry very soon.

“Hm,” komencis la Muso kun tre impona mieno “ĉu ĉiuj estas pretaj? Jen la plej bona sekigaĵo kiun mi konas. Silentu ĉiuj, mi petas! ‘Vilhelmo Venkinto, kies aferon la papo subtenis, baldaŭ subigis la anglan popolon, kiu pro manko de probatalantoj alkutimiĝis dum la lastaj jaroj al uzurpado kaj venkiĝo. Edvino kaj Morkaro, grafoj de Mercio kaj Nortumbrio——’”

'Ahem!' said the Mouse with an important air, 'are you all ready? This is the driest thing I know. Silence all round, if you please! "William the Conqueror, whose cause was favoured by the pope, was soon submitted to by the English, who wanted leaders, and had been of late much accustomed to usurpation and conquest. Edwin and Morcar, the earls of Mercia and Northumbria—"'

“Ho, ve!” ĝemis la Loro, frosttremante.

'Ugh!' said the Lory, with a shiver.

“Pardonu,” diris la Muso tre ĝentile (kvankam li tre sulkigis la brovojn), “ĉu vi parolis?”

'I beg your pardon!' said the Mouse, frowning, but very politely: 'Did you speak?'

“Ne mi,” la Loro rapide respondis.

'Not I!' said the Lory hastily.

“Mi kredis ke jes,” diris la Muso. “Sed mi daŭrigu. ‘Edvino kaj Morkaro grafoj de Mercio kaj Nortumbrio fariĝis liaj partianoj, kaj eĉ Stigando la patrujama ĉefepiskopo de Canterbury trovis ĝin konsilinda——”

'I thought you did,' said the Mouse. '—I proceed. "Edwin and Morcar, the earls of Mercia and Northumbria, declared for him: and even Stigand, the patriotic archbishop of Canterbury, found it advisable—"'

“Trovis kion?” diris la Anaso.

'Found WHAT?' said the Duck.

“Trovis ĝin,” la Muso respondis iom malafable. “Ĉu vi ne komprenas kion signifas ‘ĝi’?”

'Found IT,' the Mouse replied rather crossly: 'of course you know what "it" means.'

“Nu, mi tre bone komprenas kion ‘ĝi’ signifas, kiam mi trovas ion. Plej ofte ‘ĝi’ estas rano aŭ vermo. Tamen la demando estas: kion trovis la ĉefepiskopo?”

'I know what "it" means well enough, when I find a thing,' said the Duck: 'it's generally a frog or a worm. The question is, what did the archbishop find?'

“Tiun demandon la Muso ne atentis sed daŭrigis rapide: ‘trovis ĝin konsilinda iri kun Edgar Atheling por renkonti Vilhelmon kaj proponi al li la kronon. Sed la insulta fiero de liaj Normanoj—‘ kiel vi sentas vin nun, mia kara?” ĝi diris abrupte, alparolante Alicion.

The Mouse did not notice this question, but hurriedly went on, '"—found it advisable to go with Edgar Atheling to meet William and offer him the crown. William's conduct at first was moderate. But the insolence of his Normans—" How are you getting on now, my dear?' it continued, turning to Alice as it spoke.

“Malseka, same malseka kiel en la komenco,” Alicio respondis iom melankolie. “Via rakonto ne sekigas min.”

'As wet as ever,' said Alice in a melancholy tone: 'it doesn't seem to dry me at all.'

“Kon‐sid‐er‐ad‐inte la ĵus anonc‐itan rezult‐at‐on,” ekdiris solene la Dodo, “mi proponas ke ĉi tiu kunsido tuj fermiĝu por ke oni el‐kon‐sid‐er‐adu kaj senprokraste ef‐ekt‐iv‐ig‐u pli energiajn ri‐med‐ojn.”

'In that case,' said the Dodo solemnly, rising to its feet, 'I move that the meeting adjourn, for the immediate adoption of more energetic remedies—'

“Kian lingvon vi parolas?” demandis la Agleto. “De tiuj longaj vortoj mi ne scias la signifon, kaj plue mi kredas ke vi ne scias mem.”

'Speak English!' said the Eaglet. 'I don't know the meaning of half those long words, and, what's more, I don't believe you do either!' And the Eaglet bent down its head to hide a smile: some of the other birds tittered audibly.

La Agleto deklinis la kapon por kaŝi sian mokridon, sed kelkaj el la birdoj sibleridis aŭdeble. La Dodo per voĉo ofendita reparolis pli simple: “Jen kion mi intencis diri: la plej bona rimedo por sekigi nin estus la ‘Kaŭko’‐vetkuro.”

'What I was going to say,' said the Dodo in an offended tone, 'was, that the best thing to get us dry would be a Caucus-race.'

“Kio do estas Kaŭko?” diris Alicio. Tiun demandon ŝi faris, ne dezirante la informon, sed nur ĉar ŝi rimarkis ke la Dodo paŭzas kaj ŝajne opinias ke iu devas paroli, kaj ĉar neniu alia montris la inklinon paroli.

'What IS a Caucus-race?' said Alice; not that she wanted much to know, but the Dodo had paused as if it thought that SOMEBODY ought to speak, and no one else seemed inclined to say anything.

La Dodo respondis ke: “La plej bona rimedo por klarigi ĝin estas per la ago mem.” (Kaj ĉar ian vintran tagon vi eble volos mem eksperimenti la ludon, mi klarigos kiamaniere la Dodo aranĝis ĝin.)

'Why,' said the Dodo, 'the best way to explain it is to do it.' (And, as you might like to try the thing yourself, some winter day, I will tell you how the Dodo managed it.)

Unue, ĝi markis per kreto rondforman kurejon (la preciza formo ne gravas). Due, ĝi starigis ĉiujn partoprenontojn ĉe diversaj punktoj de la kretstreko. Oni ne diris, laŭ angla kutimo, “unu, du, tri, FOR!” sed ĉiu devis komenci kaj ĉesi la kuradon laŭ sia propra inklino, kaj pro tio ne estis facile kompreni kiam la afero finiĝis. Tamen post longa kurado, eble duonhora, ĉiuj tute resekiĝis, kaj la Dodo subite ekkriis: “La Kaŭko finiĝis.”

Ĉiuj amasiĝis ĉirkaŭ la Dodo, spiregante kaj demandante: “Sed kiu venkis?”

First it marked out a race-course, in a sort of circle, ('the exact shape doesn't matter,' it said,) and then all the party were placed along the course, here and there. There was no 'One, two, three, and away,' but they began running when they liked, and left off when they liked, so that it was not easy to know when the race was over. However, when they had been running half an hour or so, and were quite dry again, the Dodo suddenly called out 'The race is over!' and they all crowded round it, panting, and asking, 'But who has won?'

Tiun demandon la Dodo en la unua momento ne povis respondi.

Ĝi sidis longan tempon kun unu fingro premata sur la frunto (en tiu sama sintenado kiun ordinare havas Ŝejkspir en niaj bildoj). En la fino la Dodo diris:—“Ĉiuj venkis, kaj ĉiu devas ricevi premion.”

This question the Dodo could not answer without a great deal of thought, and it sat for a long time with one finger pressed upon its forehead (the position in which you usually see Shakespeare, in the pictures of him), while the rest waited in silence. At last the Dodo said, 'EVERYBODY has won, and all must have prizes.'

Plena ĥoro da voĉoj demandis samtempe: “Sed kiu la premiojn disdonos?”

'But who is to give the prizes?' quite a chorus of voices asked.

“Ja ŝi kompreneble,” diris la Dodo, kaj montris per unu fingro sur Alicion. Sekve, la tuta aro amasiĝis ĉirkaŭ ŝi kaj kriis konfuze “La premiojn, la premiojn.”

'Why, SHE, of course,' said the Dodo, pointing to Alice with one finger; and the whole party at once crowded round her, calling out in a confused way, 'Prizes! Prizes!'

Kion fari? La kompatinda Alicio havanta alian ideon neniun, enŝovis la manon en sian poŝon kaj feliĉe trovis tie pakaĵeton da sukeraĵoj (kiujn per bonŝanco la sala akvo ne difektis) kaj ilin ŝi disdonacis kiel premiojn. Sufiĉis ĝuste por donaci al ĉiuj po unu.

Alice had no idea what to do, and in despair she put her hand in her pocket, and pulled out a box of comfits, (luckily the salt water had not got into it), and handed them round as prizes. There was exactly one a-piece all round.

“Sed ŝi mem nepre rajtas ricevi premion,” diris la Muso.

'But she must have a prize herself, you know,' said the Mouse.

“Certe,” tre serioze respondis la Dodo, kaj turnis sin al Alicio dirante:

“Kion alian vi havas en la poŝo?”

'Of course,' the Dodo replied very gravely. 'What else have you got in your pocket?' he went on, turning to Alice.

Alicio respondis malĝoje ke “nur fingroingon.”

'Only a thimble,' said Alice sadly.

“Ĝin transdonu al mi,” diris la Dodo.

'Hand it over here,' said the Dodo.

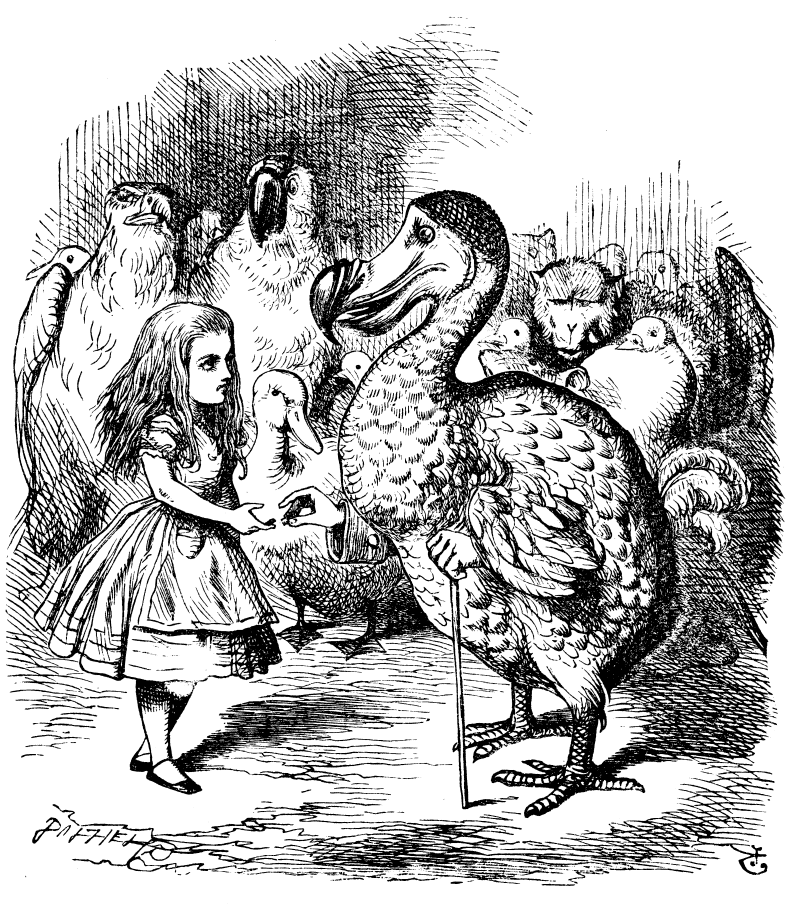

Denove ĉiuj amasiĝis ĉirkaŭ ŝi, dum la Dodo solene prezentis la fingroingon dirante: “Ni petas ke vi bonvolu akcepti ĉi tiun elegantan fingroingon.” Ĉe la fino de tiu mallonga parolo ĉiuj aplaŭdis. La Dodo solene prezentas al Alicio ŝian propran fingroingon.

Then they all crowded round her once more, while the Dodo solemnly presented the thimble, saying 'We beg your acceptance of this elegant thimble'; and, when it had finished this short speech, they all cheered.

Alicio pensis interne ke la tuta afero estas absurda, sed ĉiuj tenadis sin tiel serioze ke ŝi ne kuraĝis ridi. Ankaŭ ĉar ŝi ne povis elpensi ion dirindan, ŝi nur simple klinis respekte la kapon akceptante la ingon, kaj tenadis sin kiel eble plej serioze.

Alice thought the whole thing very absurd, but they all looked so grave that she did not dare to laugh; and, as she could not think of anything to say, she simply bowed, and took the thimble, looking as solemn as she could.

Kaj nun sekvis la manĝado de la sukeraĵoj. Tio kaŭzis ne malmulte da bruo kaj konfuzo. Grandaj birdoj plendis ke ili ne povas gustumi siajn; malgrandaj aliflanke sufokiĝis, kaj estis necese kuraci ilin per la dorsfrapada kuraco. Tamen ĉio fine elfariĝis. Ili sidigis sin denove en la rondo kaj petis al la Muso ke ĝi rakontu al ili ion plu.

The next thing was to eat the comfits: this caused some noise and confusion, as the large birds complained that they could not taste theirs, and the small ones choked and had to be patted on the back. However, it was over at last, and they sat down again in a ring, and begged the Mouse to tell them something more.

“Vi ja promesis rakonti al mi vian historion,” diris Alicio, “kaj la kaŭzon pro kiu vi malamas la... la... la... Ko kaj Ho.” Tiujn komencajn literojn ŝi aldonis per tre mallaŭta flustro, ektimante ke ĝi ree ofendiĝos.

'You promised to tell me your history, you know,' said Alice, 'and why it is you hate—C and D,' she added in a whisper, half afraid that it would be offended again.

“Mia tejlo,” diris la Muso, “estas tre longa kaj tre malĝoja.”

'Mine is a long and a sad tale!' said the Mouse, turning to Alice, and sighing.

“Mi vidas ke ĝi estas longa,” diris Alicio rigardante kun miro ĝian voston, “sed kial vi ĝin nomas malĝoja?” Kaj dum la daŭro de la rakonto ŝi tiel konfuzis sin pri tiu enigmo ke ŝia koncepto pri ĝi enhavis kune la ideojn de ambaŭ tejlaĵoj. Jen la vostrakonto aŭ rakontvosto:

'It IS a long tail, certainly,' said Alice, looking down with wonder at the Mouse's tail; 'but why do you call it sad?' And she kept on puzzling about it while the Mouse was speaking, so that her idea of the tale was something like this:—

Furi’ diris al

Mus’, kiun

trafis

li ĵus,

‘Ni havu

proceson,

procesos mi

vin! Ne ekpenu

rifuzi; tio,

nur por amuzi

min, estas

necesa; defendu

do vin!’

‘Ne utilus,

sinjor’;

diris mus’ kun

fervor’—

‘Sen juĝistoj

procesi

tempperdo

ja estas.’

‘Mi vin

juĝos

tutsole’

—diris li

ruzparole.

Li muson

kondamnis;

nun

sola

li

restas.

'Fury said to a

mouse, That he

met in the

house,

"Let us

both go to

law: I will

prosecute

YOU.—Come,

I'll take no

denial; We

must have a

trial: For

really this

morning I've

nothing

to do."

Said the

mouse to the

cur, "Such

a trial,

dear Sir,

With

no jury

or judge,

would be

wasting

our

breath."

"I'll be

judge, I'll

be jury,"

Said

cunning

old Fury:

"I'll

try the

whole

cause,

and

condemn

you

to

death."'

“Vi ne atentas,” diris la Muso al Alicio kun severa mieno. “Pri kio vi pensas?”

'You are not attending!' said the Mouse to Alice severely. 'What are you thinking of?'

“Pardonu,” respondis ŝi tre humile, “vi jam alvenis ĉe la kvina vostkurbo, ĉu ne?”

'I beg your pardon,' said Alice very humbly: 'you had got to the fifth bend, I think?'

“Mi ne!” ekkriis la Muso.

'I had NOT!' cried the Mouse, sharply and very angrily.

“Mine’, mine’,” ripetis Alicio “do vi certe estas franca Muso; sed kial vi, katmalamanto, nun alvokas katon?”

'A knot!' said Alice, always ready to make herself useful, and looking anxiously about her. 'Oh, do let me help to undo it!'

La kolerema Muso tuj levis sin kaj ekforiris, ĵetante post si la riproĉon:

“Ne tolereble estas ke vi insultu min per tia sensencaĵo.”

'I shall do nothing of the sort,' said the Mouse, getting up and walking away. 'You insult me by talking such nonsense!'

“Mi ne intencis ofendi, vere ne!” ekkriis Alicio per petega voĉo “kaj vi ja estas tre ofendema.” Anstataŭ respondi, la Muso nur graŭlis kolere.

'I didn't mean it!' pleaded poor Alice. 'But you're so easily offended, you know!'

The Mouse only growled in reply.

“Revenu, mi petegas, kaj finu la rakonton,” Alicio laŭte kriis al la foriranta Muso. Poste ĉiuj kriis ĥore: “Jes, revenu, revenu.” Tamen la Muso nur skuis malpacience la kapon, plirapidigis la paŝojn, kaj malaperis.

'Please come back and finish your story!' Alice called after it; and the others all joined in chorus, 'Yes, please do!' but the Mouse only shook its head impatiently, and walked a little quicker.

La Loro malkontente diris: “Estas domaĝo ke ĝi ne volis reveni,” unu maljuna krabino profitis la okazon por diri al la filino: “Ha, mia kara, tio estu por vi solena averto por ke neniam vi perdu la bonhumoron,” kaj la malrespekta krabido akre respondis: “Vi fermu la buŝon, panjo; vi ja difektus la paciencon eĉ al ostro.”

'What a pity it wouldn't stay!' sighed the Lory, as soon as it was quite out of sight; and an old Crab took the opportunity of saying to her daughter 'Ah, my dear! Let this be a lesson to you never to lose YOUR temper!' 'Hold your tongue, Ma!' said the young Crab, a little snappishly. 'You're enough to try the patience of an oyster!'

“Ho, kiel mi volus ke nia Dajna estu tie ĉi,” Alicio diris tion al neniu aparte sed kvazaŭ ŝi volis mem aŭdi siajn pensojn, “ŝi ja kapablus tuj reporti ĝin.”

'I wish I had our Dinah here, I know I do!' said Alice aloud, addressing nobody in particular. 'She'd soon fetch it back!'

“Kiu do estas Dajna, se estas permesite tion demandi,” diris ĝentile la Loro.

'And who is Dinah, if I might venture to ask the question?' said the Lory.

Alicio respondis avide, ĉar ĉiam ŝi estis preta paroli pri sia kara katinjo. “Dajna estas mia kato. Ŝi estas la plej bona muskaptisto kiun vi povus eĉ imagi; kaj se vi vidus ŝin birdkaptanta, …”

Alice replied eagerly, for she was always ready to talk about her pet: 'Dinah's our cat. And she's such a capital one for catching mice you can't think! And oh, I wish you could see her after the birds! Why, she'll eat a little bird as soon as look at it!'

Tiuj vortoj kaŭzis inter la ĉeestantoj vere rimarkindajn sentojn. Kelkaj el la birdoj tuj forportis sin. Unu maljuna pigo tre zorge enfaldis sin per la vestoj kaj anoncis ke, ĉar la noktaj vaporoj malbone efikas sur la gorĝo, ŝi devas hejmeniĝi. La kanario kriis per trempepanta voĉo al siaj idoj: “Forvenu, karuletoj, la horo jam pasis, je kiu vi devis kuŝiĝi.”

Pro diversaj tiaj pretekstoj ĉiuj foriris unu post alia, ĝis Alicio restis tute sola.

This speech caused a remarkable sensation among the party. Some of the birds hurried off at once: one old Magpie began wrapping itself up very carefully, remarking, 'I really must be getting home; the night-air doesn't suit my throat!' and a Canary called out in a trembling voice to its children, 'Come away, my dears! It's high time you were all in bed!' On various pretexts they all moved off, and Alice was soon left alone.

“Se nur mi ne estus nominta Dajna’n!” ŝi diris melankolie. “Supre en la hejmo ĉiuj ŝatas ŝin, ĉi tie funde, neniu. Tamen, laŭ mi, ŝi estas la plej bona kato en la tuta mondo. Ho, Dajna, vi kara Dajna, ĉu jam neniam mi revidos vin?” Kaj nun sentante sin tre sola kaj tre malĝoja, ŝi denove ekploris.

Post iom da tempo, ekaŭdante kelkajn piedpaŝetaĵojn, ŝi avide direktis la rigardojn al ili, en la espero ke eble la Muso regajnis la bonhumoron kaj nun revenas por fini sian rakonton.

'I wish I hadn't mentioned Dinah!' she said to herself in a melancholy tone. 'Nobody seems to like her, down here, and I'm sure she's the best cat in the world! Oh, my dear Dinah! I wonder if I shall ever see you any more!' And here poor Alice began to cry again, for she felt very lonely and low-spirited. In a little while, however, she again heard a little pattering of footsteps in the distance, and she looked up eagerly, half hoping that the Mouse had changed his mind, and was coming back to finish his story.

Audio from LibreVox.org

Audio from LibreVox.org