Las aventuras de Alicia en el País de las Maravillas

Capítulo XII

CHAPTER XII.

La declaración de Alicia

Alice's Evidence

-¡Estoy aquí! -gritó Alicia.

Y olvidando, en la emoción del momento, lo mucho que había crecido en los últimos minutos, se puso en pie con tal precipitación que golpeó con el borde de su falda el estrado de los jurados, y todos los miembros del jurado cayeron de cabeza encima de la gente que había debajo, y quedaron allí pataleando y agitándose, y esto le recordó a Alicia intensamente la pecera de peces de colores que ella había volcado sin querer la semana pasada.

'Here!' cried Alice, quite forgetting in the flurry of the moment how large she had grown in the last few minutes, and she jumped up in such a hurry that she tipped over the jury-box with the edge of her skirt, upsetting all the jurymen on to the heads of the crowd below, and there they lay sprawling about, reminding her very much of a globe of goldfish she had accidentally upset the week before.

-¡Oh, les ruego me perdonen! -exclamó Alicia en tono consternado.

Y empezó a levantarlos a toda prisa, pues no podía apartar de su mente el accidente de la pecera, y tenía la vaga sensación de que era preciso recogerlas cuanto antes y devolverlos al estrado, o de lo contrario morirían.

'Oh, I BEG your pardon!' she exclaimed in a tone of great dismay, and began picking them up again as quickly as she could, for the accident of the goldfish kept running in her head, and she had a vague sort of idea that they must be collected at once and put back into the jury-box, or they would die.

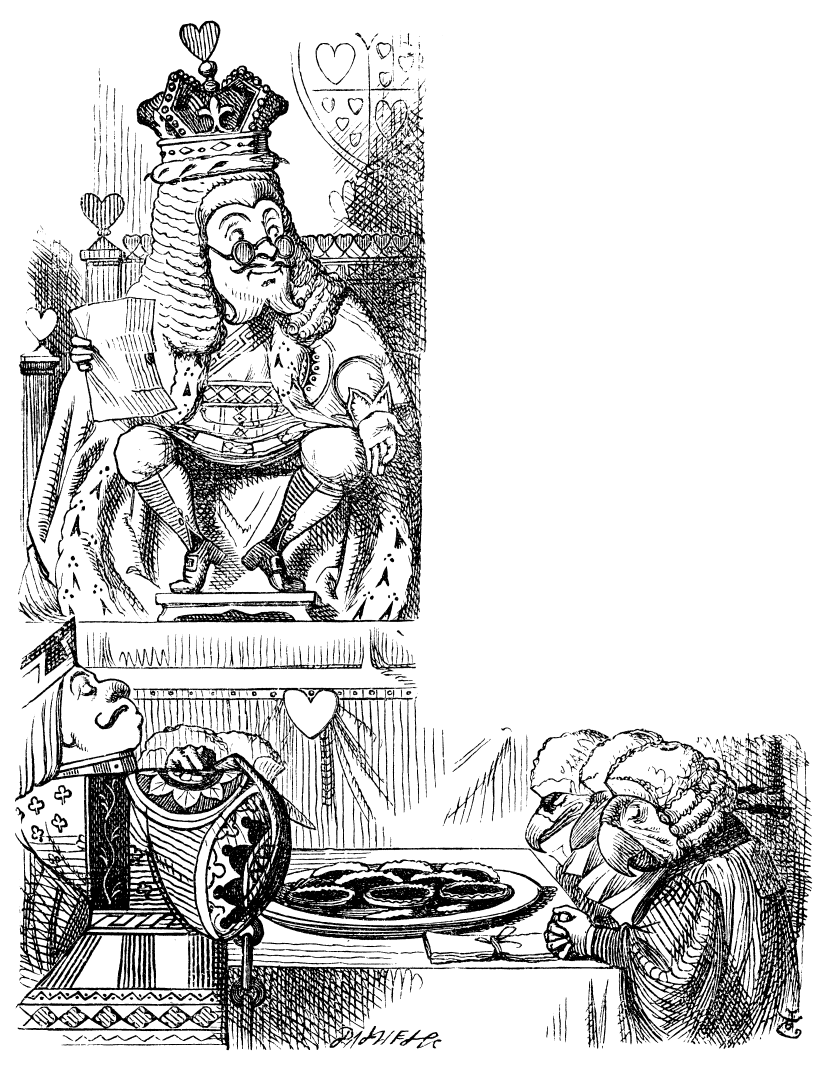

-El juicio no puede seguir -dijo el Rey con voz muy grave- hasta que todos los miembros del jurado hayan ocupado debidamente sus puestos... todos los miembros del jurado -repitió con mucho énfasis, mirando severamente a Alicia mientras decía estas palabras.

'The trial cannot proceed,' said the King in a very grave voice, 'until all the jurymen are back in their proper places—ALL,' he repeated with great emphasis, looking hard at Alice as he said do.

Alicia miró hacia el estrado del jurado, y vio que, con las prisas, había colocado a la Lagartija cabeza abajo, y el pobre animalito, incapaz de incorporarse, no podía hacer otra cosa que agitar melancólicamente la cola. Alicia lo cogió inmediatamente y lo colocó en la postura adecuada.

«Aunque no creo que sirva de gran cosa», se dijo para sí. «Me parece que el juicio no va a cambiar en nada por el hecho de que este animalito esté de pies o de cabeza.»

Alice looked at the jury-box, and saw that, in her haste, she had put the Lizard in head downwards, and the poor little thing was waving its tail about in a melancholy way, being quite unable to move. She soon got it out again, and put it right; 'not that it signifies much,' she said to herself; 'I should think it would be QUITE as much use in the trial one way up as the other.'

Tan pronto como el jurado se hubo recobrado un poco del shock que había sufrido, y hubo encontrado y enarbolado de nuevo sus tizas y pizarras, se pusieron todos a escribir con gran diligencia para consignar la historia del accidente. Todos menos la Lagartija, que parecía haber quedado demasiado impresionada para hacer otra cosa que estar sentada allí, con la boca abierta, los ojos fijos en el techo de la sala.

As soon as the jury had a little recovered from the shock of being upset, and their slates and pencils had been found and handed back to them, they set to work very diligently to write out a history of the accident, all except the Lizard, who seemed too much overcome to do anything but sit with its mouth open, gazing up into the roof of the court.

-¿Qué sabes tú de este asunto? -le dijo el Rey a Alicia.

'What do you know about this business?' the King said to Alice.

-Nada -dijo Alicia.

'Nothing,' said Alice.

-¿Nada de nada? -insistió el Rey.

'Nothing WHATEVER?' persisted the King.

-Nada de nada -dijo Alicia.

'Nothing whatever,' said Alice.

-Esto es algo realmente trascendente -dijo el Rey, dirigiéndose al jurado.

Y los miembros del jurado estaban empezando a anotar esto en sus pizarras, cuando intervino a toda prisa el Conejo Blanco: -Naturalmente, Su Majestad ha querido decir intrascendente –dijo en tono muy respetuoso, pero frunciendo el ceño y haciéndole signos de inteligencia al Rey mientras hablaba.

Intrascendente es lo que he querido decir, naturalmente -se apresuró a decir el Rey.

'That's very important,' the King said, turning to the jury. They were just beginning to write this down on their slates, when the White Rabbit interrupted: 'UNimportant, your Majesty means, of course,' he said in a very respectful tone, but frowning and making faces at him as he spoke.

Y empezó a mascullar para sí: «Trascendente... intrascendente... trascendente... intrascendente...», como si estuviera intentando decidir qué palabra sonaba mejor.

'UNimportant, of course, I meant,' the King hastily said, and went on to himself in an undertone, 'important—unimportant—unimportant—important—' as if he were trying which word sounded best.

Parte del jurado escribió «trascendente», y otra parte escribió «intrascendente». Alicia pudo verlo, pues estaba lo suficiente cerca de los miembros del jurado para leer sus pizarras. «Pero esto no tiene la menor importancia», se dijo para sí.

Some of the jury wrote it down 'important,' and some 'unimportant.' Alice could see this, as she was near enough to look over their slates; 'but it doesn't matter a bit,' she thought to herself.

En este momento el Rey, que había estado muy ocupado escribiendo algo en su libreta de notas, gritó: « ¡Silencio!», y leyó en su libreta:

-Artículo Cuarenta y Dos. Toda persona que mida más de un kilómetro tendrá que abandonar la sala.

At this moment the King, who had been for some time busily writing in his note-book, cackled out 'Silence!' and read out from his book, 'Rule Forty-two. ALL PERSONS MORE THAN A MILE HIGH TO LEAVE THE COURT.'

Todos miraron a Alicia.

Everybody looked at Alice.

-Yo no mido un kilómetro -protestó Alicia.

'I'M not a mile high,' said Alice.

-Sí lo mides -dijo el Rey.

'You are,' said the King.

-Mides casi dos kilómetros añadió la Reina.

'Nearly two miles high,' added the Queen.

-Bueno, pues no pienso moverme de aquí, de todos modos -aseguró Alicia-. Y además este artículo no vale: usted lo acaba de inventar.

'Well, I shan't go, at any rate,' said Alice: 'besides, that's not a regular rule: you invented it just now.'

-Es el artículo más viejo de todo el libro -dijo el Rey.

'It's the oldest rule in the book,' said the King.

-En tal caso, debería llevar el Número Uno -dijo Alicia.

'Then it ought to be Number One,' said Alice.

El Rey palideció, y cerró a toda prisa su libro de notas.

-¡Considerad vuestro veredicto! -ordenó al jurado, en voz débil y temblorosa.

The King turned pale, and shut his note-book hastily. 'Consider your verdict,' he said to the jury, in a low, trembling voice.

-Faltan todavía muchas pruebas, con la venia de Su Majestad –dijo el Conejo Blanco, poniéndose apresuradamente de pie-. Acaba de encontrarse este papel.

'There's more evidence to come yet, please your Majesty,' said the White Rabbit, jumping up in a great hurry; 'this paper has just been picked up.'

-¿Qué dice este papel? -preguntó la Reina.

'What's in it?' said the Queen.

-Todavía no lo he abierto -contestó el Conejo Blanco-, pero parece ser una carta, escrita por el prisionero a... a alguien.

'I haven't opened it yet,' said the White Rabbit, 'but it seems to be a letter, written by the prisoner to—to somebody.'

-Así debe ser -asintió el Rey-, porque de lo contrario hubiera sido escrita a nadie, lo cual es poco frecuente.

'It must have been that,' said the King, 'unless it was written to nobody, which isn't usual, you know.'

-¿A quién va dirigida? -preguntó uno de los miembros del jurado.

'Who is it directed to?' said one of the jurymen.

-No va dirigida a nadie -dijo el Conejo Blanco-. No lleva nada escrito en la parte exterior. -Desdobló el papel, mientras hablaba, y añadió-: Bueno, en realidad no es una carta: es una serie de versos.

'It isn't directed at all,' said the White Rabbit; 'in fact, there's nothing written on the OUTSIDE.' He unfolded the paper as he spoke, and added 'It isn't a letter, after all: it's a set of verses.'

-¿Están en la letra del acusado? -preguntó otro de los miembros del jurado.

'Are they in the prisoner's handwriting?' asked another of the jurymen.

-No, no lo están -dijo el Conejo Blanco-, y esto es lo más extraño de todo este asunto. (Todos los miembros del jurado quedaron perplejos.)

'No, they're not,' said the White Rabbit, 'and that's the queerest thing about it.' (The jury all looked puzzled.)

-Debe de haber imitado la letra de otra persona -dijo el Rey. (Todos los miembros del jurado respiraron con alivio.)

'He must have imitated somebody else's hand,' said the King. (The jury all brightened up again.)

-Con la venia de Su Majestad -dijo el Valet-, yo no he escrito este papel, y nadie puede probar que lo haya hecho, porque no hay ninguna firma al final del escrito.

'Please your Majesty,' said the Knave, 'I didn't write it, and they can't prove I did: there's no name signed at the end.'

-Si no lo has firmado -dijo el Rey-, eso no hace más que agravar tu culpa. Lo tienes que haber escrito con mala intención, o de lo contrario habrías firmado con tu nombre como cualquier persona honrada.

'If you didn't sign it,' said the King, 'that only makes the matter worse. You MUST have meant some mischief, or else you'd have signed your name like an honest man.'

Un unánime aplauso siguió a estas palabras: en realidad, era la primera cosa sensata que el Rey había dicho en todo el día.

There was a general clapping of hands at this: it was the first really clever thing the King had said that day.

-Esto prueba su culpabilidad, naturalmente -exclamó la Reina-. Por lo tanto, que le corten...

'That PROVES his guilt,' said the Queen.

-¡Esto no prueba nada de nada! -protestó Alicia-. ¡Si ni siquiera sabemos lo que hay escrito en el papel!

'It proves nothing of the sort!' said Alice. 'Why, you don't even know what they're about!'

-Léelo -ordenó el Rey al Conejo Blanco.

'Read them,' said the King.

El Conejo Blanco se puso las gafas. -¿Por dónde debo empezar, con la venia de Su Majestad? -preguntó.

The White Rabbit put on his spectacles. 'Where shall I begin, please your Majesty?' he asked.

-Empieza por el principio -dijo el Rey con gravedad- y sigue hasta llegar al final; allí te paras.

'Begin at the beginning,' the King said gravely, 'and go on till you come to the end: then stop.'

Se hizo un silencio de muerte en la sala, mientras el Conejo Blanco leía los siguientes versos:

These were the verses the White Rabbit read:—

Dijeron que fuiste a verla Y que a él le hablaste de mí: Ella aprobó mi carácter Y yo a nadar no aprendí.

'They told me you had been to her,

And mentioned me to him:

She gave me a good character,

But said I could not swim.

Él dijo que yo no era (Bien sabemos que es verdad): Pero si ella insistiera ¿Qué te podría pasar?

He sent them word I had not gone

(We know it to be true):

If she should push the matter on,

What would become of you?

Yo di una, ellos dos, Tú nos diste tres o más, Todas volvieron a ti, y eran Mías tiempo atrás.

I gave her one, they gave him two,

You gave us three or more;

They all returned from him to you,

Though they were mine before.

Si ella o yo tal vez nos vemos Mezclados en este lío, Él espera tú los libres Y sean como al principio.

If I or she should chance to be

Involved in this affair,

He trusts to you to set them free,

Exactly as we were.

Me parece que tú fuiste (Antes del ataque de ella), Entre él, y yo y aquello Un motivo de querella.

My notion was that you had been

(Before she had this fit)

An obstacle that came between

Him, and ourselves, and it.

No dejes que él sepa nunca Que ella los quería más, Pues debe ser un secreto Y entre tú y yo ha de quedar.

Don't let him know she liked them best,

For this must ever be

A secret, kept from all the rest,

Between yourself and me.'

-¡Ésta es la prueba más importante que hemos obtenido hasta ahora! -dijo el Rey, frotándose las manos-. Así pues, que el jurado proceda a...

'That's the most important piece of evidence we've heard yet,' said the King, rubbing his hands; 'so now let the jury—'

-Si alguno de vosotros es capaz de explicarme este galimatías, -dijo Alicia (había crecido tanto en los últimos minutos que no le daba ningún miedo interrumpir al Rey) -le doy seis peniques.Yo estoy convencida de que estos versos no tienen pies ni cabeza.

'If any one of them can explain it,' said Alice, (she had grown so large in the last few minutes that she wasn't a bit afraid of interrupting him,) 'I'll give him sixpence. I don't believe there's an atom of meaning in it.'

Todos los miembros del jurado escribieron en sus pizarras: «Ella está convencida de que estos versos no tienen pies ni cabeza», pero ninguno de ellos se atrevió a explicar el contenido del escrito.

The jury all wrote down on their slates, 'SHE doesn't believe there's an atom of meaning in it,' but none of them attempted to explain the paper.

-Si el poema no tiene sentido -dijo el Rey-, eso nos evitará muchas complicaciones, porque no tendremos que buscárselo. Y, sin embargo -siguió, apoyando el papel sobre sus rodillas y mirándolo con ojos entornados-, me parece que yo veo algún significado... Y yo a nadar no aprendí... Tú no sabes nadar, ¿o sí sabes? -añadió, dirigiéndose al Valet.

'If there's no meaning in it,' said the King, 'that saves a world of trouble, you know, as we needn't try to find any. And yet I don't know,' he went on, spreading out the verses on his knee, and looking at them with one eye; 'I seem to see some meaning in them, after all. "—SAID I COULD NOT SWIM—" you can't swim, can you?' he added, turning to the Knave.

El Valet sacudió tristemente la cabeza.

-¿Tengo yo aspecto de saber nadar? -dijo. (Desde luego no lo tenía, ya que estaba hecho enteramente de cartón.)

The Knave shook his head sadly. 'Do I look like it?' he said. (Which he certainly did NOT, being made entirely of cardboard.)

-Hasta aquí todo encaja -observó el Rey, y siguió murmurando para sí mientras examinaba los versos-: Bien sabemos que es verdad... Evidentemente se refiere al jurado... Pero si ella insistiera... Tiene que ser la Reina... ¿Qué te podría pasar?... ¿Qué, en efecto? Yo di una, ellos dos... Vaya, esto debe ser lo que él hizo con las tartas...

'All right, so far,' said the King, and he went on muttering over the verses to himself: '"WE KNOW IT TO BE TRUE—" that's the jury, of course—"I GAVE HER ONE, THEY GAVE HIM TWO—" why, that must be what he did with the tarts, you know—'

-Pero después sigue todas volvieron a ti -observó Alicia.

'But, it goes on "THEY ALL RETURNED FROM HIM TO YOU,"' said Alice.

-¡Claro, y aquí están! -exclamó triunfalmente el Rey, señalando las tartas que había sobre la mesa. Está más claro que el agua. Y más adelante... Antes del ataque de ella... ¿Tú nunca tienes ataques, verdad, querida? -le dijo a la Reina.

'Why, there they are!' said the King triumphantly, pointing to the tarts on the table. 'Nothing can be clearer than THAT. Then again—"BEFORE SHE HAD THIS FIT—" you never had fits, my dear, I think?' he said to the Queen.

-¡Nunca! -rugió la Reina furiosa, arrojando un tintero contra la pobre Lagartija.

(La infeliz Lagartija había renunciado ya a escribir en su pizarra con el dedo, porque se dio cuenta de que no dejaba marca, pero ahora se apresuró a empezar de nuevo, aprovechando la tinta que le caía chorreando por la cara, todo el rato que pudo.)

'Never!' said the Queen furiously, throwing an inkstand at the Lizard as she spoke. (The unfortunate little Bill had left off writing on his slate with one finger, as he found it made no mark; but he now hastily began again, using the ink, that was trickling down his face, as long as it lasted.)

-Entonces las palabras del verso no pueden atacarte a ti -dijo el Rey, mirando a su alrededor con una sonrisa.

Había un silencio de muerte.

'Then the words don't FIT you,' said the King, looking round the court with a smile. There was a dead silence.

-¡Es un juego de palabras! -tuvo que explicar el Rey con acritud.

Y ahora todos rieron.

-¡Que el jurado considere su veredicto! -ordenó el Rey, por centésima vez aquel día.

'It's a pun!' the King added in an offended tone, and everybody laughed, 'Let the jury consider their verdict,' the King said, for about the twentieth time that day.

-¡No! ¡No! -protestó la Reina-. Primero la sentencia... El veredicto después.

'No, no!' said the Queen. 'Sentence first—verdict afterwards.'

-¡Valiente idiotez! -exclamó Alicia alzando la voz-. ¡Qué ocurrencia pedir la sentencia primero!

'Stuff and nonsense!' said Alice loudly. 'The idea of having the sentence first!'

-¡Cállate la boca! -gritó la Reina, poniéndose color púrpura.

'Hold your tongue!' said the Queen, turning purple.

-¡No quiero! -dijo Alicia.

'I won't!' said Alice.

-¡Que le corten la cabeza! -chilló la Reina a grito pelado.

Nadie se movió.

'Off with her head!' the Queen shouted at the top of her voice. Nobody moved.

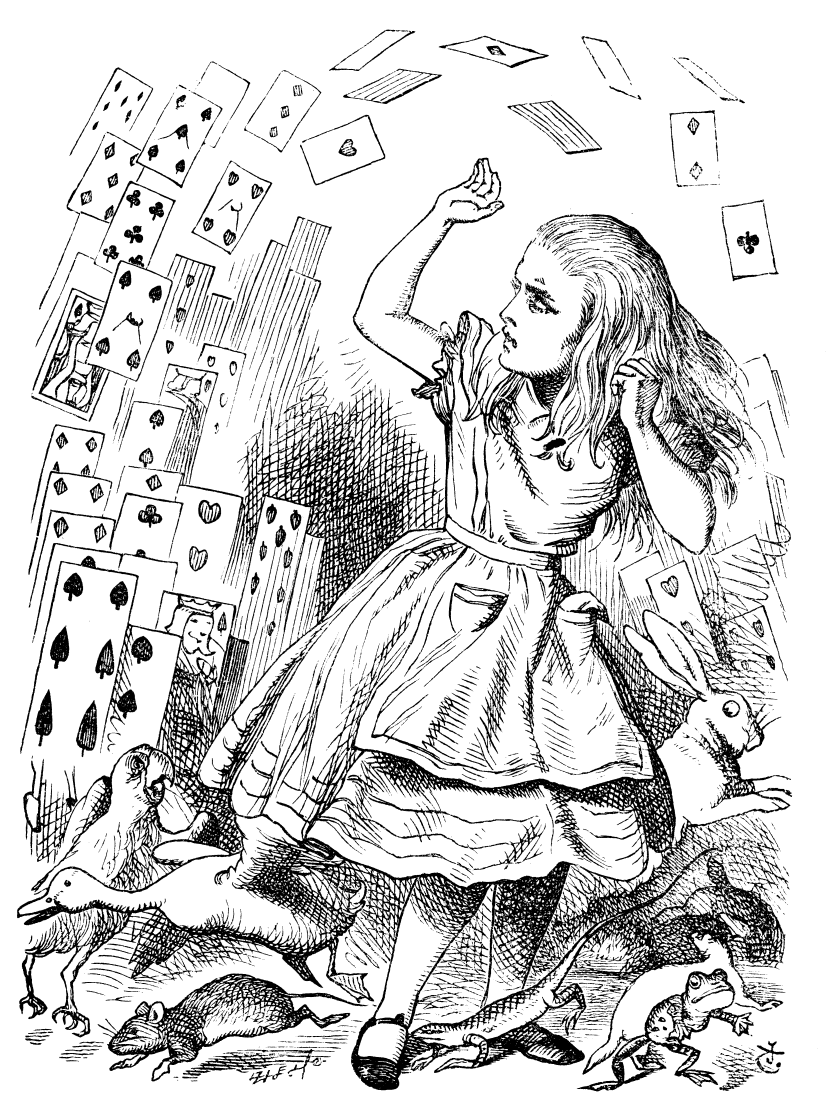

-¿Quién le va a hacer caso? -dijo Alicia (al llegar a este momento ya había crecido hasta su estatura normal)-. ¡No sois todos más que una baraja de cartas!

'Who cares for you?' said Alice, (she had grown to her full size by this time.) 'You're nothing but a pack of cards!'

Al oír esto la baraja se elevó por los aires y se precipitó en picada contra ella. Alicia dio un pequeño grito, mitad de miedo y mitad de enfado, e intentó sacárselos de encima... Y se encontró tumbada en la ribera, con la cabeza apoyada en la falda de su hermana, que le estaba quitando cariñosamente de la cara unas hojas secas que habían caído desde los árboles.

At this the whole pack rose up into the air, and came flying down upon her: she gave a little scream, half of fright and half of anger, and tried to beat them off, and found herself lying on the bank, with her head in the lap of her sister, who was gently brushing away some dead leaves that had fluttered down from the trees upon her face.

-¡Despierta ya, Alicia! -le dijo su hermana-. ¡Cuánto rato has dormido!

'Wake up, Alice dear!' said her sister; 'Why, what a long sleep you've had!'

-¡Oh, he tenido un sueño tan extraño! -dijo Alicia.

Y le contó a su hermana, tan bien como sus recuerdos lo permitían, todas las sorprendentes aventuras que hemos estado leyendo. Y, cuando hubo terminado, su hermana le dio un beso y le dijo:

-Realmente, ha sido un sueño extraño, cariño. Pero ahora corre a merendar. Se está haciendo tarde.

Así pues, Alicia se levantó y se alejó corriendo de allí, y mientras corría no dejó de pensar en el maravilloso sueño que había tenido.

'Oh, I've had such a curious dream!' said Alice, and she told her sister, as well as she could remember them, all these strange Adventures of hers that you have just been reading about; and when she had finished, her sister kissed her, and said, 'It WAS a curious dream, dear, certainly: but now run in to your tea; it's getting late.' So Alice got up and ran off, thinking while she ran, as well she might, what a wonderful dream it had been.

Pero su hermana siguió sentada allí, tal como Alicia la había dejado, la cabeza apoyada en una mano, viendo cómo se ponía el sol y pensando en la pequeña Alicia y en sus maravillosas aventuras. Hasta que también ella empezó a soñar a su vez, y éste fue su sueño:

But her sister sat still just as she left her, leaning her head on her hand, watching the setting sun, and thinking of little Alice and all her wonderful Adventures, till she too began dreaming after a fashion, and this was her dream:—

Primero, soñó en la propia Alicia, y le pareció sentir de nuevo las manos de la niña apoyadas en sus rodillas y ver sus ojos brillantes y curiosos fijos en ella. Oía todos los tonos de su voz y veía el gesto con que apartaba los cabellos que siempre le caían delante de los ojos. Y mientras los oía, o imaginaba que los oía, el espacio que la rodeaba cobró vida y se pobló con los extraños personajes del sueño de su hermana.

First, she dreamed of little Alice herself, and once again the tiny hands were clasped upon her knee, and the bright eager eyes were looking up into hers—she could hear the very tones of her voice, and see that queer little toss of her head to keep back the wandering hair that WOULD always get into her eyes—and still as she listened, or seemed to listen, the whole place around her became alive with the strange creatures of her little sister's dream.

La alta hierba se agitó a sus pies cuando pasó corriendo el Conejo Blanco; el asustado Ratón chapoteó en un estanque cercano; pudo oír el tintineo de las tazas de porcelana mientras la Liebre de Marzo y sus amigos proseguían aquella merienda interminable, y la penetrante voz de la Reina ordenando que se cortara la cabeza a sus invitados; de nuevo el bebé-cerdito estornudó en brazos de la Duquesa, mientras platos y fuentes se estrellaban a su alrededor; de nuevo se llenó el aire con los graznidos del Grifo, el chirriar de la tiza de la Lagartija y los aplausos de los «reprimidos» conejillos de indias, mezclado todo con el distante sollozar de la Falsa Tortuga.

The long grass rustled at her feet as the White Rabbit hurried by—the frightened Mouse splashed his way through the neighbouring pool—she could hear the rattle of the teacups as the March Hare and his friends shared their never-ending meal, and the shrill voice of the Queen ordering off her unfortunate guests to execution—once more the pig-baby was sneezing on the Duchess's knee, while plates and dishes crashed around it—once more the shriek of the Gryphon, the squeaking of the Lizard's slate-pencil, and the choking of the suppressed guinea-pigs, filled the air, mixed up with the distant sobs of the miserable Mock Turtle.

La hermana de Alicia estaba sentada allí, con los ojos cerrados, y casi creyó encontrarse ella también en el País de las Maravillas. Pero sabía que le bastaba volver a abrir los ojos para encontrarse de golpe en la aburrida realidad. La hierba sería sólo agitada por el viento, y el chapoteo del estanque se debería al temblor de las cañas que crecían en él. El tintineo de las tazas de té se transformaría en el resonar de unos cencerros, y la penetrante voz de la Reina en los gritos de un pastor. Y los estornudos del bebé, los graznidos del Grifo, y todos los otros ruidos misteriosos, se transformarían (ella lo sabía) en el confuso rumor que llegaba desde una granja vecina, mientras el lejano balar de los rebaños sustituía los sollozos de la Falsa Tortuga.

So she sat on, with closed eyes, and half believed herself in Wonderland, though she knew she had but to open them again, and all would change to dull reality—the grass would be only rustling in the wind, and the pool rippling to the waving of the reeds—the rattling teacups would change to tinkling sheep-bells, and the Queen's shrill cries to the voice of the shepherd boy—and the sneeze of the baby, the shriek of the Gryphon, and all the other queer noises, would change (she knew) to the confused clamour of the busy farm-yard—while the lowing of the cattle in the distance would take the place of the Mock Turtle's heavy sobs.

Por último, imaginó cómo sería, en el futuro, esta pequeña hermana suya, cómo sería Alicia cuando se convirtiera en una mujer. Y pensó que Alicia conservaría, a lo largo de los años, el mismo corazón sencillo y entusiasta de su niñez, y que reuniría a su alrededor a otros chiquillos, y haría brillar los ojos de los pequeños al contarles un cuento extraño, quizás este mismo sueño del País de las Maravillas que había tenido años atrás; y que Alicia sentiría las pequeñas tristezas y se alegraría con los ingenuos goces de los chiquillos, recordando su propia infancia y los felices días del verano.

Lastly, she pictured to herself how this same little sister of hers would, in the after-time, be herself a grown woman; and how she would keep, through all her riper years, the simple and loving heart of her childhood: and how she would gather about her other little children, and make THEIR eyes bright and eager with many a strange tale, perhaps even with the dream of Wonderland of long ago: and how she would feel with all their simple sorrows, and find a pleasure in all their simple joys, remembering her own child-life, and the happy summer days.

FIN

THE END

Audio from LibreVox.org