不思議の国のアリス

12.

CHAPTER XII.

アリスのしょうこ

Alice's Evidence

「ここです!」とアリスは声をあげ、いっしゅんこうふんしてここ数分で自分がどれほど大きくなったかをすっかりわすれ、あわてて立ち上がりすぎて、陪審席をスカートのはしにひっかけてたおしてしまい、おかげで陪審たちがその下のぼうちょう席に、頭から浴びせられることになってしまいました。そしてみんなベシャッと横になって、アリスは先週うっかりひっくりかえした金魚鉢のようすを、まざまざと思いだしました。

'Here!' cried Alice, quite forgetting in the flurry of the moment how large she had grown in the last few minutes, and she jumped up in such a hurry that she tipped over the jury-box with the edge of her skirt, upsetting all the jurymen on to the heads of the crowd below, and there they lay sprawling about, reminding her very much of a globe of goldfish she had accidentally upset the week before.

「あらほんとうにごめんなさい!」アリスはうろたえてさけび、できるだけすばやくみんなをひろいあげました。金魚鉢の事故が頭のなかをかけめぐって、なんだかすぐにあつめて陪審席にもどしてあげないと、みんなすぐに死んじゃうような気がばくぜんとしたのです。

'Oh, I BEG your pardon!' she exclaimed in a tone of great dismay, and began picking them up again as quickly as she could, for the accident of the goldfish kept running in her head, and she had a vague sort of idea that they must be collected at once and put back into the jury-box, or they would die.

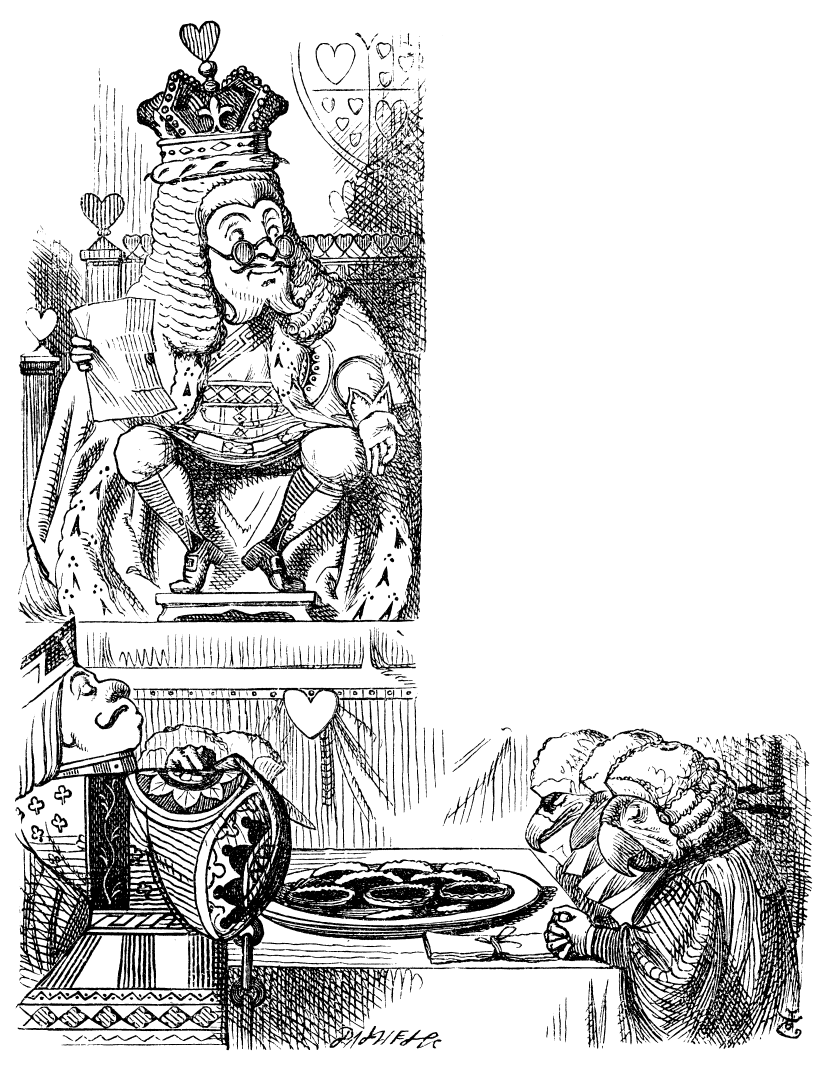

王さまがとてもおもおもしい声でもうします。「陪審員が全員しかるべきいちにもどらないかぎり、裁判をすすめることはできない――全員、だぞ」と、とても強くくりかえしながら、アリスをにらみつけます。

'The trial cannot proceed,' said the King in a very grave voice, 'until all the jurymen are back in their proper places—ALL,' he repeated with great emphasis, looking hard at Alice as he said do.

陪審席をみてみると、あわてていたせいで、トカゲをさかさにつっこんでしまったのがわかりました。かわいそうなトカゲはかなしそうにしっぽをふって、まるでみうごきができずにいたのです。すぐに出してあげて、ちゃんともどしてあげました。「でもべつにたいしたちがいじゃないと思うけれど。あのトカゲなら、さかさだろうと裁判にはまるっきりえいきょうしないと思う」とアリスは考えます。

Alice looked at the jury-box, and saw that, in her haste, she had put the Lizard in head downwards, and the poor little thing was waving its tail about in a melancholy way, being quite unable to move. She soon got it out again, and put it right; 'not that it signifies much,' she said to herself; 'I should think it would be QUITE as much use in the trial one way up as the other.'

陪審たちが、ひっくりかえされたショックからすこし立ちなおり、石板と石筆がみつかってかえされると、みんなすぐにこの事故のけいかを、こまごまと書きつけはじめました。ただしトカゲだけはべつです。トカゲはショックがつよすぎて、口をぽかーんとあけて法廷の屋根を見あげながら、すわっているだけでした。

As soon as the jury had a little recovered from the shock of being upset, and their slates and pencils had been found and handed back to them, they set to work very diligently to write out a history of the accident, all except the Lizard, who seemed too much overcome to do anything but sit with its mouth open, gazing up into the roof of the court.

「このいっけんについて、なにを知っておるかね?」王さまはアリスにききました。

'What do you know about this business?' the King said to Alice.

「なんにも」とアリス。

'Nothing,' said Alice.

「なにもまったく?」と王さまがねんをおします。

'Nothing WHATEVER?' persisted the King.

「なにもまったく」とアリス。

'Nothing whatever,' said Alice.

「これはきわめて重要(じゅうよう)じゃ」と王さまはばいしんにむかって言いました。ばいしんたちがこれを石板に書き始めたところで、白うさぎが口をはさみます。「非重要(ひじゅうよう)と、もちろん王さまはいわんとしたのです」その口ぶりはとってもそんけいがこもっていましたが、でも言いながら王さまにむかって、しかめっつらをして変な顔をしてみせています。

'That's very important,' the King said, turning to the jury. They were just beginning to write this down on their slates, when the White Rabbit interrupted: 'UNimportant, your Majesty means, of course,' he said in a very respectful tone, but frowning and making faces at him as he spoke.

「非重要(ひじゅうよう)じゃ、もちろんわしのいわんとしたのは」と王さまはあわてて言いました。そしてそのあとで「重要(じゅうよう)――非重要(ひじゅうよう)――重要(じゅうよう)――非重要(ひじゅうよう)――」と小声でぶつぶつつぶやいて、どっちのことばがしっくりくるかを決めようとしてるみたいでした。

'UNimportant, of course, I meant,' the King hastily said, and went on to himself in an undertone, 'important—unimportant—unimportant—important—' as if he were trying which word sounded best.

陪審(ばいしん)のなかには「重要(じゅうよう)」と書いたのもいたし、「非重要(ひじゅうよう)」と書いたのもいました。アリスは石板をのぞきこめるくらい近くにいたのです。「でもどうだっていいや」と思いました。

Some of the jury wrote it down 'important,' and some 'unimportant.' Alice could see this, as she was near enough to look over their slates; 'but it doesn't matter a bit,' she thought to herself.

このとき、しばらくノートにいろいろねっしんに書きつけていた王さまが「せいしゅくに!」とかなきり声をあげて、ほうりつ書をよみあげました。「規則だい四十二番。身のたけ1キロ以上のものは、すべて法廷を出なくてはならない」

At this moment the King, who had been for some time busily writing in his note-book, cackled out 'Silence!' and read out from his book, 'Rule Forty-two. ALL PERSONS MORE THAN A MILE HIGH TO LEAVE THE COURT.'

みんなアリスのほうを見ました。

Everybody looked at Alice.

「あたし、身長一キロもないもん!」とアリス。

'I'M not a mile high,' said Alice.

「あるね」と王さま。

'You are,' said the King.

「二キロ近くあるね」と女王さま。

'Nearly two miles high,' added the Queen.

「ふん、どっちにしても、あたしは出ていきませんからね。それに、いまのはちゃんとした規則じゃないわ。いまでっちあげただけでしょう」

'Well, I shan't go, at any rate,' said Alice: 'besides, that's not a regular rule: you invented it just now.'

「ほうりつ書で一番ふるい規則じゃ」と王さま。

'It's the oldest rule in the book,' said the King.

「だったら規則一番のはずだわ」とアリス。

'Then it ought to be Number One,' said Alice.

王さまはまっさおになり、ノートをあわててとじました。そして陪審にむかって小さなふるえる声で「判決を考えるがよい」ともうしました。

The King turned pale, and shut his note-book hastily. 'Consider your verdict,' he said to the jury, in a low, trembling voice.

「まだしょうこが出てまいります、おねがいですから陛下」と白うさぎがあわてて飛び上がりました。「ちょうどこのかみきれが手に入りましたのです」

'There's more evidence to come yet, please your Majesty,' said the White Rabbit, jumping up in a great hurry; 'this paper has just been picked up.'

「なにが書いてあるのじゃ?」と女王さま。

'What's in it?' said the Queen.

「まだあけておりませんで」と白うさぎ。「でもなにやら手紙のようで。囚人が書いたもののようです――だれかにあてて」

'I haven't opened it yet,' said the White Rabbit, 'but it seems to be a letter, written by the prisoner to—to somebody.'

「そうだったにちがいない。ただし、だれにもあてていないかもしれないぞ、めったにないことではあるがな」と王さま。

'It must have been that,' said the King, 'unless it was written to nobody, which isn't usual, you know.'

「だれあて?」と陪審の一人。

'Who is it directed to?' said one of the jurymen.

「あて先がまったくないのです。じつは、外側にはなにも書かれていないのです」こういいながら、白うさぎはかみをひらいて、つけたしました。「やっぱり手紙ではありませんでした。詩です」

'It isn't directed at all,' said the White Rabbit; 'in fact, there's nothing written on the OUTSIDE.' He unfolded the paper as he spoke, and added 'It isn't a letter, after all: it's a set of verses.'

「囚人の筆跡かい?」とべつの陪審がききます。

'Are they in the prisoner's handwriting?' asked another of the jurymen.

「それがちがうのです。一番なぞめいた部分ですな」と白うさぎ。(陪審たちはみんな、ふしんそうな顔をします。)

'No, they're not,' said the White Rabbit, 'and that's the queerest thing about it.' (The jury all looked puzzled.)

「だれか別人の筆跡をまねたにちがいない」と王さま(陪審たちはみんな、顔がパッとあかるくなりました)。

'He must have imitated somebody else's hand,' said the King. (The jury all brightened up again.)

「おねがいです、陛下。わたしは書いておりませんし、だれもわたしが書いたとは証明できないはずです。最後にしょめいもないじゃないですか」とジャック。

'Please your Majesty,' said the Knave, 'I didn't write it, and they can't prove I did: there's no name signed at the end.'

「しょめいしなかったのなら、なおわるい。きさまはまちがいなくなにかをたくらんでおったろう。さもなければ、正直者としてちゃんとしょめいをしたであろうからな!」と王さま。

'If you didn't sign it,' said the King, 'that only makes the matter worse. You MUST have meant some mischief, or else you'd have signed your name like an honest man.'

これにはあちこちではくしゅがおこりました。この日、王さまが言ったはじめての、まともにかしこいことだったからです。

There was a general clapping of hands at this: it was the first really clever thing the King had said that day.

「これであやつのゆうざいが証明された」と女王さま。

'That PROVES his guilt,' said the Queen.

「ぜんぜんそんな証明にはならないわ!」とアリス。「だいたいみんな、なにが書いてあるかもまだ知らないくせに!」

'It proves nothing of the sort!' said Alice. 'Why, you don't even know what they're about!'

「読むがよい」と王さま。

'Read them,' said the King.

白うさぎはめがねをかけます。「どこからはじめましょうか、陛下?」

The White Rabbit put on his spectacles. 'Where shall I begin, please your Majesty?' he asked.

王さまはおもおもしくもうします。「はじめからはじめるがよい。そして最後にくるまでつづけるのじゃ。そうしたらとまれ」

'Begin at the beginning,' the King said gravely, 'and go on till you come to the end: then stop.'

白うさぎが読みあげた詩は、こんなものでした:

These were the verses the White Rabbit read:—

「きみが彼女のところへいって、

ぼくのことを彼に話したときいた:

彼女はぼくをほめてはくれたが、

ぼくが泳げないといった。

'They told me you had been to her,

And mentioned me to him:

She gave me a good character,

But said I could not swim.

彼はみんなにぼくが去っていないと報せた

(これが事実なのはわかっている):

彼女がこの件を追求したら、

きみはいったいどうなる?

He sent them word I had not gone

(We know it to be true):

If she should push the matter on,

What would become of you?

ぼくは彼女に一つやり、みんなはかれに二つやり、

きみはぼくらに三つ以上くれた:

みんな彼からきみへもどった、

かつてはみんなぼくのだったのに。

I gave her one, they gave him two,

You gave us three or more;

They all returned from him to you,

Though they were mine before.

もしぼくか彼女がたまさか

この事件に巻き込まれたら

彼はきみにかれらを解放してくれという、

ちょうどむかしのぼくらのように。

If I or she should chance to be

Involved in this affair,

He trusts to you to set them free,

Exactly as we were.

ぼくの考えではきみこそが

(彼女がこのかんしゃくを起こす前は)

彼とわれわれとそれとの間に

割って入った障害だったのだ。

My notion was that you had been

(Before she had this fit)

An obstacle that came between

Him, and ourselves, and it.

彼女がかれらを一番気に入っていたと彼に悟られるな

というのもこれは永遠の秘密、

ほかのだれも知らない、

きみとぼくだけの秘密だから」

Don't let him know she liked them best,

For this must ever be

A secret, kept from all the rest,

Between yourself and me.'

「これまできいたなかで、もっとも重要なしょうこぶっけんじゃ」と王さまは、手もみしながらもうします。「では陪審は判決を――」

'That's the most important piece of evidence we've heard yet,' said the King, rubbing his hands; 'so now let the jury—'

「あのなかのだれでも、いまの詩を説明できるもんなら、六ペンスあげるわよ」(アリスはこの数分ですごく大きくなったので、王さまの話をさえぎっても、ちっともこわくなかったんだ)「あたしはあんな詩、これっぽっちも意味はないと思うわ」

'If any one of them can explain it,' said Alice, (she had grown so large in the last few minutes that she wasn't a bit afraid of interrupting him,) 'I'll give him sixpence. I don't believe there's an atom of meaning in it.'

陪審(ばいしん)はみんな、石板に書きつけました。「この女性はあんな詩、これっぽっちも意味はないと思う」でもだれもそれを説明しようとはしません。

The jury all wrote down on their slates, 'SHE doesn't believe there's an atom of meaning in it,' but none of them attempted to explain the paper.

「これっぽっちも意味がないなら、いろいろてまがはぶけてこうつごうじゃ、意味をさがすまでもないんじゃからの。しかしどうかな」と王さまは、詩をひざのうえにひろげ、かた目でながめてつづけます。「どうもなにかしら意味はよみとれるように思うんじゃがの。『――泳げないといった――』おまえ、泳げないじゃろ?」と王さまはジャックのほうをむきます。

'If there's no meaning in it,' said the King, 'that saves a world of trouble, you know, as we needn't try to find any. And yet I don't know,' he went on, spreading out the verses on his knee, and looking at them with one eye; 'I seem to see some meaning in them, after all. "—SAID I COULD NOT SWIM—" you can't swim, can you?' he added, turning to the Knave.

ジャックはかなしそうに首をふりました。「泳げそうに見えます?」(たしかに見えなかったね、ぜんしんがボールがみでできていたもの)。

The Knave shook his head sadly. 'Do I look like it?' he said. (Which he certainly did NOT, being made entirely of cardboard.)

「いまのところはよいようじゃな」と王さまは、詩をぶつぶつつぶやきながら、先をつづけます。「『これが事実なのはわかってる』――これはもちろん陪審じゃな――『ぼくは彼女に一つやり、みんなはかれに二つやり』――なんと、これはこやつがタルトでしでかしたことではないか――」

'All right, so far,' said the King, and he went on muttering over the verses to himself: '"WE KNOW IT TO BE TRUE—" that's the jury, of course—"I GAVE HER ONE, THEY GAVE HIM TWO—" why, that must be what he did with the tarts, you know—'

「でも、『みんな彼からきみへもどった』ってつづいてるじゃないの」とアリス。

'But, it goes on "THEY ALL RETURNED FROM HIM TO YOU,"' said Alice.

「ほうれ、そこにもどっておるではないか!」と王さまは勝ちほこって、テーブルのタルトを指さしました。「明々白々ではないか。しかし――『彼女がこのかんしゃくを起こす前』とは――つまよ、おまえはかんしゃくなど起こしたことはないと思うが?」と王さまは女王さまにもうしました。

'Why, there they are!' said the King triumphantly, pointing to the tarts on the table. 'Nothing can be clearer than THAT. Then again—"BEFORE SHE HAD THIS FIT—" you never had fits, my dear, I think?' he said to the Queen.

「一度もないわ!」と女王は怒り狂って、あわせてインクスタンドをトカゲに投げつけました。(かわいそうなビルは、あれから一本指で石板に書くのをあきらめていました。なんのあともつかなかったからです。でもいまや急いでまた書きはじめました。自分の頭をつたいおちてくるインキを、なくなるまで使ったのです)

'Never!' said the Queen furiously, throwing an inkstand at the Lizard as she spoke. (The unfortunate little Bill had left off writing on his slate with one finger, as he found it made no mark; but he now hastily began again, using the ink, that was trickling down his face, as long as it lasted.)

「ではこの詩があてはまらなくてかんしゃ(く)しよう」といって王さまは、にっこりと法廷を見まわしました。あたりはしーんとしています。

'Then the words don't FIT you,' said the King, looking round the court with a smile. There was a dead silence.

「しゃれじゃ!」と王さまが、むっとしたようにつけたしますと、みんなわらいました。「では陪審は判決を考えるように」と王さまが言います。もうこれで二十回目くらいです。

'It's a pun!' the King added in an offended tone, and everybody laughed, 'Let the jury consider their verdict,' the King said, for about the twentieth time that day.

「ちがうちがう! まずは処刑――判決はあとじゃ!」と女王さま。

'No, no!' said the Queen. 'Sentence first—verdict afterwards.'

「ばかげてるにもほどがある!」とアリスが大声でいいました。「処刑を先にするなんて!」

'Stuff and nonsense!' said Alice loudly. 'The idea of having the sentence first!'

「口をつつしみおろう!」女王さまは、むらさき色になっちゃってます。

'Hold your tongue!' said the Queen, turning purple.

「いやよ!」とアリス。

'I won't!' said Alice.

「あやつの首をちょん切れ!」女王さまは、声をからしてさけびます。だれも身動きしません。

'Off with her head!' the Queen shouted at the top of her voice. Nobody moved.

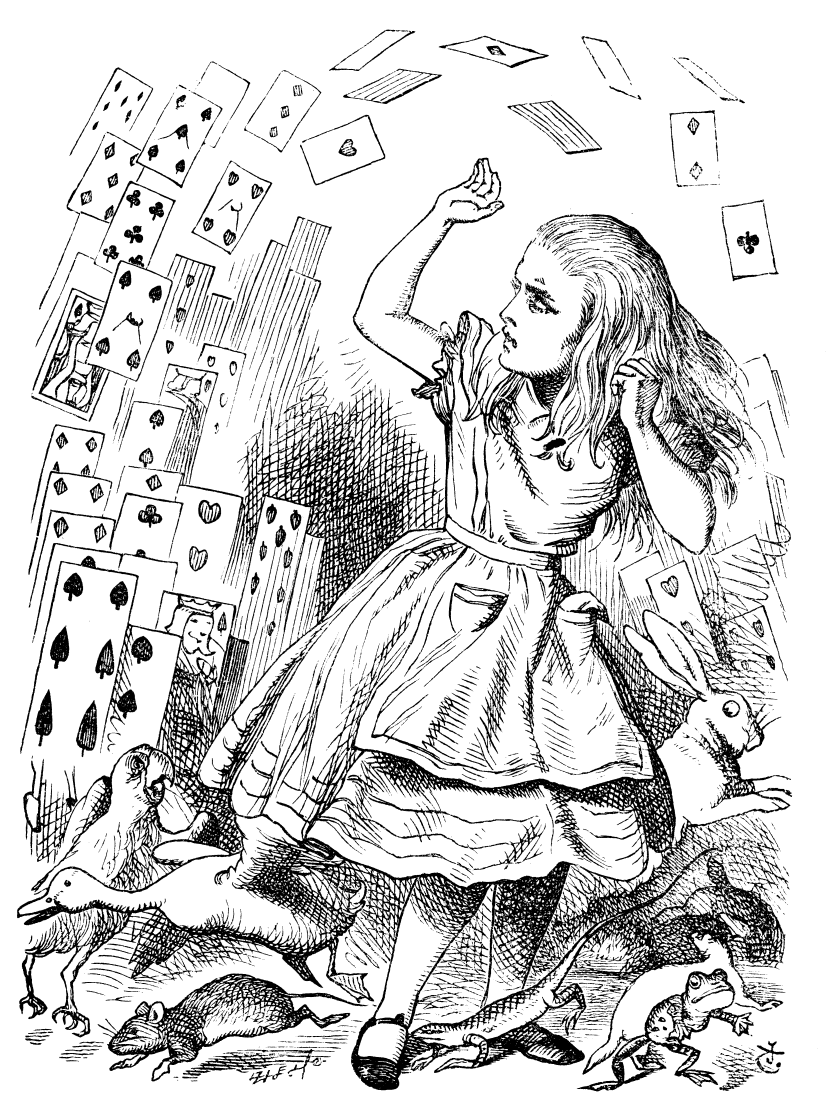

「だれがあんたたちなんか気にするもんですか!」とアリス(このときには、もう完全にもとの大きさにもどってたんだ)「ただのトランプの束のくせに!」

'Who cares for you?' said Alice, (she had grown to her full size by this time.) 'You're nothing but a pack of cards!'

これと同時に、トランプすべてが宙にまいあがって、アリスのうえにとびかかってきました。アリスはちょっとひめいをあげて、半分こわくて半分怒って、それをはらいのけようとして、気がつくと川辺によこになって、おねえさんのひざに頭をのせているのでした。そしておねえさんは、木からアリスの顔にひらひら落ちてきた枯れ葉を、やさしくはらいのけているところでした。

At this the whole pack rose up into the air, and came flying down upon her: she gave a little scream, half of fright and half of anger, and tried to beat them off, and found herself lying on the bank, with her head in the lap of her sister, who was gently brushing away some dead leaves that had fluttered down from the trees upon her face.

「おきなさい、アリスちゃん! まったく、ずいぶんよくねてたのね!」

'Wake up, Alice dear!' said her sister; 'Why, what a long sleep you've had!'

「ね、すっごくへんな夢を見たの!」とアリスはおねえさんに言って、あなたがこれまで読んできた、この不思議な冒険を、おもいだせるかぎり話してあげたのでした。そしてアリスの話がおわると、おねえさんはアリスにキスして言いました。「それはとってもふうがわりな夢だったわねえ、ええ。でもそろそろ走ってお茶にいってらっしゃい。もう時間もおそいし」そこでアリスは立ちあがってかけだし、走りながらも、なんてすてきな夢だったんだろう、と心から思うのでした。

'Oh, I've had such a curious dream!' said Alice, and she told her sister, as well as she could remember them, all these strange Adventures of hers that you have just been reading about; and when she had finished, her sister kissed her, and said, 'It WAS a curious dream, dear, certainly: but now run in to your tea; it's getting late.' So Alice got up and ran off, thinking while she ran, as well she might, what a wonderful dream it had been.

でもおねえさんは、アリスがいってしまってからも、じっとすわってほおづえをつきながら、夕日をながめつつアリスとそのすばらしい冒険のことを考えておりました。するとやがておねえさんも、なんとなく夢を見たのです。そしておねえさんの夢は、こんなぐあいでした。

But her sister sat still just as she left her, leaning her head on her hand, watching the setting sun, and thinking of little Alice and all her wonderful Adventures, till she too began dreaming after a fashion, and this was her dream:—

まず、おねえさんは小さなアリス自身のことを夢に見ました。そしてさっきと同じように、小さな手がこちらのひざのうえでにぎりしめられ、そして明るいいきいきとした目が、こちらの目をのぞきこんでいます――アリスの声がまざまざときこえ、いつも目にかぶさるおちつかないあのかみの毛を、へんなふり方で後ろに投げ出すあのしぐさも見えます――そしてそれをきくうちに、というかきいているつもりになるうちに、おねえさんのまわりがすべて、妹の夢の不思議な生き物にいのちをふきこむのでした。

First, she dreamed of little Alice herself, and once again the tiny hands were clasped upon her knee, and the bright eager eyes were looking up into hers—she could hear the very tones of her voice, and see that queer little toss of her head to keep back the wandering hair that WOULD always get into her eyes—and still as she listened, or seemed to listen, the whole place around her became alive with the strange creatures of her little sister's dream.

白うさぎが急ぐと、足もとで長い草がカサカサ音をたてます――おびえたネズミが近くの池の水をはねちらかして――三月うさぎとそのお友だちが、はてしない食事をともにしているお茶わんのガチャガチャいう音が聞こえます。そして運のわるいお客たちを処刑しろとめいじる、女王さまのかなきり声――またもやぶた赤ちゃんが公爵夫人のひざでくしゃみをして、まわりには大皿小皿がガシャンガシャンとふりそそいでいます――またもやグリフォンがわめき、トカゲの石筆がきしり、鎮圧されたモルモットが息をつまらせる音があたりをみたし、それがかなたのみじめなにせウミガメのすすり泣きにまじります。

The long grass rustled at her feet as the White Rabbit hurried by—the frightened Mouse splashed his way through the neighbouring pool—she could hear the rattle of the teacups as the March Hare and his friends shared their never-ending meal, and the shrill voice of the Queen ordering off her unfortunate guests to execution—once more the pig-baby was sneezing on the Duchess's knee, while plates and dishes crashed around it—once more the shriek of the Gryphon, the squeaking of the Lizard's slate-pencil, and the choking of the suppressed guinea-pigs, filled the air, mixed up with the distant sobs of the miserable Mock Turtle.

そこでおねえさんはすわりつづけました。目をとじて、そして自分が不思議の国にいるのだと、なかば信じようとしました。でも、いずれまた目をあけなくてはならないのはわかっていました。そしてそうなれば、まわりのすべてがつまらない現実にもどってしまうことも――草がカサカサいうのは、風がふいているだけだし、池はあしがゆれて水がはねているだけ――ガチャガチャいうお茶わんは、ヒツジのベルの音にかわり、女王さまのかなきり声は、ヒツジかいの男の子の声に――そして赤ちゃんのくしゃみ、グリフォンのわめきなど、いろんな不思議な音は、あわただしい農場の、いりまじったそう音にかわってしまう(おねえさんにはわかっていたんだ)――そして遠くでいななくウシの声が、にせウミガメのすすり泣きにとってかわることでしょう。

So she sat on, with closed eyes, and half believed herself in Wonderland, though she knew she had but to open them again, and all would change to dull reality—the grass would be only rustling in the wind, and the pool rippling to the waving of the reeds—the rattling teacups would change to tinkling sheep-bells, and the Queen's shrill cries to the voice of the shepherd boy—and the sneeze of the baby, the shriek of the Gryphon, and all the other queer noises, would change (she knew) to the confused clamour of the busy farm-yard—while the lowing of the cattle in the distance would take the place of the Mock Turtle's heavy sobs.

最後におねえさんは想像してみました。この自分の小さな妹が、いずれりっぱな女性に育つところを。そして大きくなってからも、子ども時代の素朴で愛しい心をわすれずにいるところを。そして、自分の小さな子どもたちをまわりにあつめ、数々の不思議なお話でその子たちの目を、いきいきとかがやかせるところを。そのお話には、ずっとむかしの不思議の国の夢だって入っているかもしれません。そして素朴なかなしみをわかちあい、素朴なよろこびをいつくしみ、自分の子ども時代を、そしてこのしあわせな夏の日々も、わすれずにいるところを。

Lastly, she pictured to herself how this same little sister of hers would, in the after-time, be herself a grown woman; and how she would keep, through all her riper years, the simple and loving heart of her childhood: and how she would gather about her other little children, and make THEIR eyes bright and eager with many a strange tale, perhaps even with the dream of Wonderland of long ago: and how she would feel with all their simple sorrows, and find a pleasure in all their simple joys, remembering her own child-life, and the happy summer days.

THE END

Audio from LibreVox.org