Аліса в Країні Чудес

Розділ другий

CHAPTER II.

Озеро сліз

The Pool of Tears

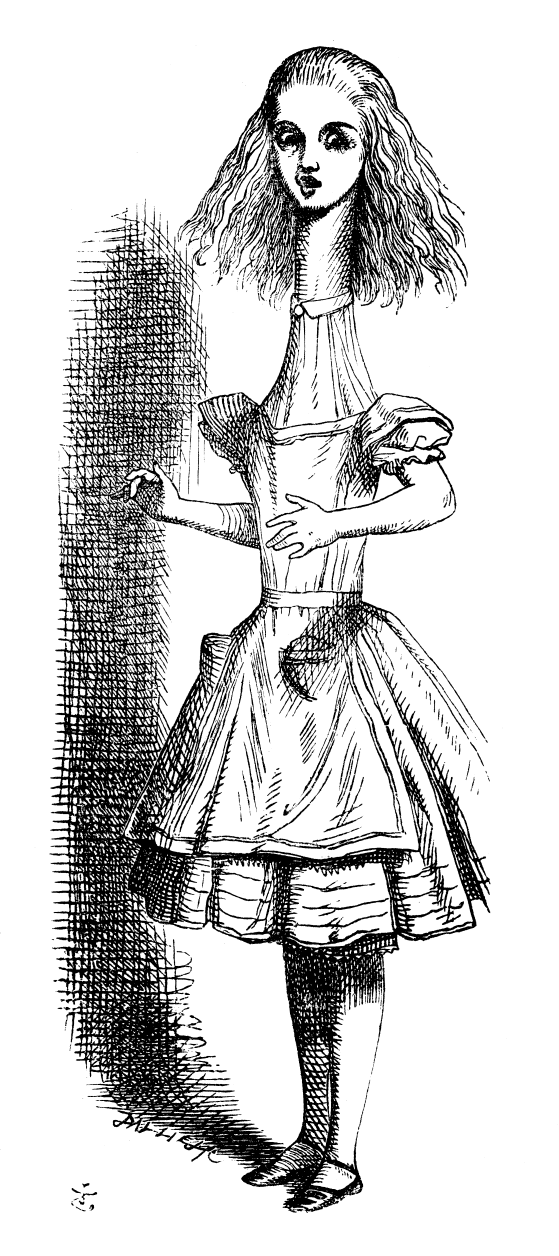

- Все дивасніше й дивасніше! - вигукнула Аліса (з великого зачудування вона раптом забула як правильно говорити). - Тепер я розтягуюсь наче найбільша в світі підзорна труба! До побачення, ноги! (Бо ніг своїх вона вже майже не бачила - так хутко вони віддалялися).

- О бідні мої ноженята, хто ж вас тепер взуватиме, у панчішки вбиратиме? Напевно не я!.. Тепер ми надто далеко одне від одного, щоб я могла дбати про вас: мусите давати собі раду самі...

"А все ж я повинна їм догоджати, - додала подумки Аліса. - Бо ще ходитимуть не туди куди я хочу!.. О, вже знаю: я на кожне Різдво даруватиму їм нові чобітки".

'Curiouser and curiouser!' cried Alice (she was so much surprised, that for the moment she quite forgot how to speak good English); 'now I'm opening out like the largest telescope that ever was! Good-bye, feet!' (for when she looked down at her feet, they seemed to be almost out of sight, they were getting so far off). 'Oh, my poor little feet, I wonder who will put on your shoes and stockings for you now, dears? I'm sure I shan't be able! I shall be a great deal too far off to trouble myself about you: you must manage the best way you can;—but I must be kind to them,' thought Alice, 'or perhaps they won't walk the way I want to go! Let me see: I'll give them a new pair of boots every Christmas.'

І вона почала міркувати, як це найкраще зробити.

- Чобітки доведеться слати з посланцем, метикувала вона. - От комедія - слати дарунки своїм власним ногам! І ще з якою чудернацькою адресою:

And she went on planning to herself how she would manage it. 'They must go by the carrier,' she thought; 'and how funny it'll seem, sending presents to one's own feet! And how odd the directions will look!

Ш-ній ПРАВІЙ НОЗІ АЛІСИНІЙ

КИЛИМОК-ПІД-КАМІНОМ

ВІД АЛІСИ, 3 ЛЮБОВ'Ю

ALICE'S RIGHT FOOT, ESQ.

HEARTHRUG,

NEAR THE FENDER,

(WITH ALICE'S LOVE).

- О людоньки, що за дурниці я верзу!

Oh dear, what nonsense I'm talking!'

Тут вона стукнулася головою об стелю: ще б пак, її зріст сягав тепер за дев'ять футів! Вона мерщій схопила золотого ключика й гайнула до садових дверцят.

Just then her head struck against the roof of the hall: in fact she was now more than nine feet high, and she at once took up the little golden key and hurried off to the garden door.

Бідолашна Аліса! Єдине, що вона могла зробити, лежачи на підлозі, - це зазирнути в садок одним оком. Надії дістатися туди лишалося ще менше, ніж досі. Вона сіла і знову зайшлася плачем.

Poor Alice! It was as much as she could do, lying down on one side, to look through into the garden with one eye; but to get through was more hopeless than ever: she sat down and began to cry again.

- Як тобі не сором! - сказала собі Аліса. - Щоб отака велика дівчинка (чим не до речі сказано?) отак розпустила рюмси! Зараз же перестань, чуєш?

Але вона все плакала й плакала, розливаючись потоками сліз, аж поки наплакала ціле озерце, завглибшки з чотири дюйми і завширшки на півкоридора.

'You ought to be ashamed of yourself,' said Alice, 'a great girl like you,' (she might well say this), 'to go on crying in this way! Stop this moment, I tell you!' But she went on all the same, shedding gallons of tears, until there was a large pool all round her, about four inches deep and reaching half down the hall.

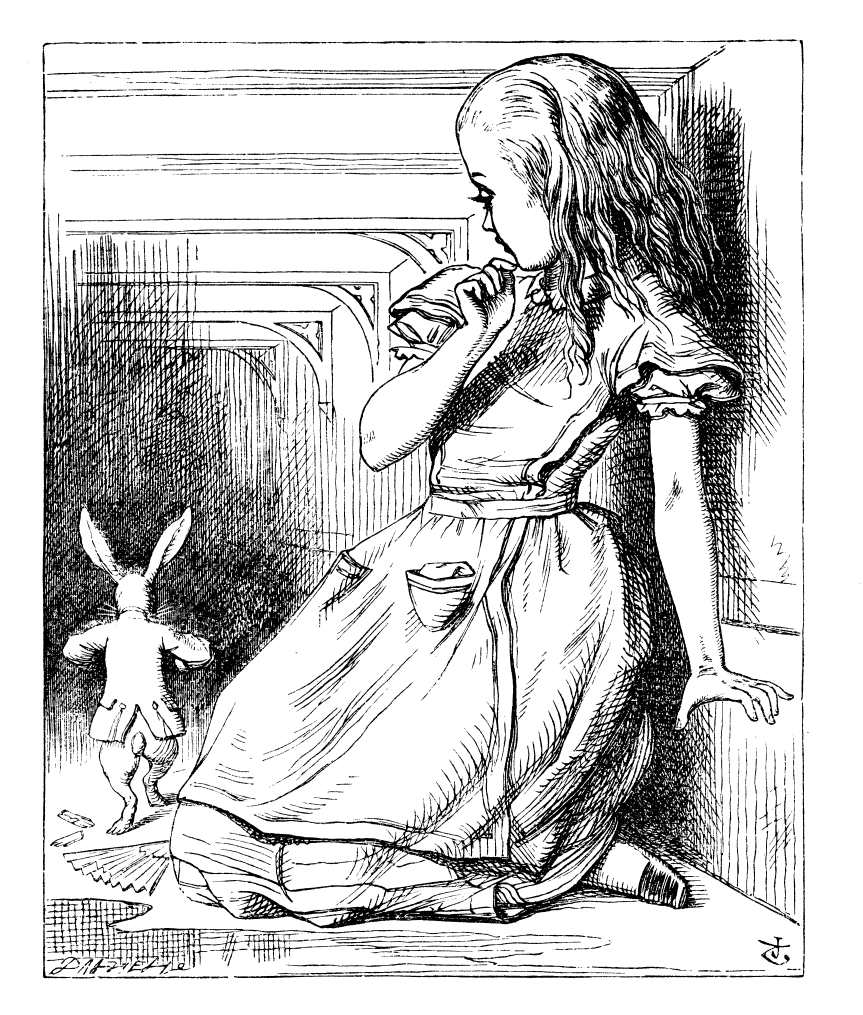

Тут до її слуху долинуло дрібне лопотіння ніг. Аліса похапцем утерла очі, аби глянути, хто це. То повертався Білий Кролик: вишукано вбраний, з парою білих лайкових рукавичок в одній руці і віялом - у другій. Він дуже поспішав і бурмотів сам до себе:

- Ой, Герцогиня! Ой-ой Герцогиня! Вона ж оскаженіє, коли я змушу її чекати!

З розпачу Аліса ладна була просити помочі в кого завгодно, тож коли Кролик порівнявся з нею, вона знічено озвалася:

- Перепрошую, пане...

Кролик аж звився на місці - кинув віяло й рукавички, і очамріло дременув у темряву.

After a time she heard a little pattering of feet in the distance, and she hastily dried her eyes to see what was coming. It was the White Rabbit returning, splendidly dressed, with a pair of white kid gloves in one hand and a large fan in the other: he came trotting along in a great hurry, muttering to himself as he came, 'Oh! the Duchess, the Duchess! Oh! won't she be savage if I've kept her waiting!' Alice felt so desperate that she was ready to ask help of any one; so, when the Rabbit came near her, she began, in a low, timid voice, 'If you please, sir—' The Rabbit started violently, dropped the white kid gloves and the fan, and skurried away into the darkness as hard as he could go.

Аліса підняла одне й друге, і стала обмахуватися віялом: задуха в коридорі стояла страшенна.

- Який божевільний день! - сказала вона. - Ще вчора все йшло нормально... Цікаво, може, це я за ніч так перемінилася? Ану пригадаймо: коли я прокинулась - чи була я такою, як завжди? Щось мені пригадується, ніби я почувалася інакше. А якщо я не та, що була, то, скажіть-но, хто я тепер?.. Оце так головоломка...

І вона почала перебирати в пам'яті усіх своїх ровесниць, аби з'ясувати, чи не перетворилася вона часом на одну з них.

Alice took up the fan and gloves, and, as the hall was very hot, she kept fanning herself all the time she went on talking: 'Dear, dear! How queer everything is to-day! And yesterday things went on just as usual. I wonder if I've been changed in the night? Let me think: was I the same when I got up this morning? I almost think I can remember feeling a little different. But if I'm not the same, the next question is, Who in the world am I? Ah, THAT'S the great puzzle!' And she began thinking over all the children she knew that were of the same age as herself, to see if she could have been changed for any of them.

- Безперечно, я - не Ада, - розмірковувала вона. - В Ади волосся спадає кучерями, а в мене - не в'ється зовсім. І, безперечно, я не Мейбл: я ж бо знаю стільки всякої всячини, а вона - ой, вона така невігласка! Крім того, вона - то вона, а я - це я, а... О людоньки, як важко в усьому цьому розібратися!.. Ану перевірмо, чи знаю я те, що знала? Отже: чотири по п'ять дванадцять, чотири по шість - тринадцять, чотири по сім - е, так я ніколи не дійду до двадцяти! Втім, таблиця множення - ще не аґрумент... Перевірмо географію: Лондон - столиця Парижу, а Париж - Риму, а Рим... Ні, все неправильно! Мабуть, я таки не я, а Мейбл! Ану, прочитаю вірша "Хороша перепілонька..."

І схрестивши руки на колінах, так ніби вона проказувала вголос уроки, Аліса стала читати з пам'яті. Але й голос її звучав хрипко та дивно, і слова були не ті:

'I'm sure I'm not Ada,' she said, 'for her hair goes in such long ringlets, and mine doesn't go in ringlets at all; and I'm sure I can't be Mabel, for I know all sorts of things, and she, oh! she knows such a very little! Besides, SHE'S she, and I'm I, and—oh dear, how puzzling it all is! I'll try if I know all the things I used to know. Let me see: four times five is twelve, and four times six is thirteen, and four times seven is—oh dear! I shall never get to twenty at that rate! However, the Multiplication Table doesn't signify: let's try Geography. London is the capital of Paris, and Paris is the capital of Rome, and Rome—no, THAT'S all wrong, I'm certain! I must have been changed for Mabel! I'll try and say "How doth the little—"' and she crossed her hands on her lap as if she were saying lessons, and began to repeat it, but her voice sounded hoarse and strange, and the words did not come the same as they used to do:—

Хороший крокодилонько

Качається в піску,

Пірнає в чисту хвиленьку,

Споліскує луску.

'How doth the little crocodile

Improve his shining tail,

And pour the waters of the Nile

On every golden scale!

Як він покаже зубоньки,

Привітно сміючись,

То рибоньки-голубоньки

Самі у рот плись-плись!

'How cheerfully he seems to grin,

How neatly spread his claws,

And welcome little fishes in

With gently smiling jaws!'

- Це явно не ті слова, - зітхнула бідолашна Аліса зі слізьми на очах. - Я таки й справді Мейбл, і доведеться мені жити в убогому будиночку, де й гратися немає чим, зате ого скільки уроків треба вчити! Ні, цього не буде: якщо я Мейбл, то залишуся тут, унизу! Нехай скільки завгодно заглядають сюди і благають: "Вернися до нас, золотко!"

Я тільки зведу очі й запитаю: "Спершу скажіть, хто я є, і, коли мені ця особа підходить - я вийду нагору, а коли ні - не вийду. Сидітиму тут, аж доки стану кимось іншим".

Тут знову з її очей бризнули сльози.

- Чому ніхто сюди навіть не загляне!.. Я так втомилася бути сама!

'I'm sure those are not the right words,' said poor Alice, and her eyes filled with tears again as she went on, 'I must be Mabel after all, and I shall have to go and live in that poky little house, and have next to no toys to play with, and oh! ever so many lessons to learn! No, I've made up my mind about it; if I'm Mabel, I'll stay down here! It'll be no use their putting their heads down and saying "Come up again, dear!" I shall only look up and say "Who am I then? Tell me that first, and then, if I like being that person, I'll come up: if not, I'll stay down here till I'm somebody else"—but, oh dear!' cried Alice, with a sudden burst of tears, 'I do wish they WOULD put their heads down! I am so VERY tired of being all alone here!'

З цими словами вона опустила очі і з подивом помітила, що, розмовляючи сама з собою, натягла на руку одну з Кроликових білих рукавичок.

- І як це мені вдалося? - майнуло у неї в голові. - Напевно, я знову меншаю?

Вона звелася й пішла до столика, аби примірятись: так і є - вона зменшилася десь до двох футів і швидко меншала далі. Причиною, як незабаром з'ясувалося, було віяло в її руці, тож Аліса прожогом його відкинула: ще мить - і вона зникла б зовсім!

As she said this she looked down at her hands, and was surprised to see that she had put on one of the Rabbit's little white kid gloves while she was talking. 'How CAN I have done that?' she thought. 'I must be growing small again.' She got up and went to the table to measure herself by it, and found that, as nearly as she could guess, she was now about two feet high, and was going on shrinking rapidly: she soon found out that the cause of this was the fan she was holding, and she dropped it hastily, just in time to avoid shrinking away altogether.

- Ху-у! Ледь урятувалася! - сказала вона, вельми налякана цими змінами, але й невимовне рада, що живе ще на світі.

- А тепер - до саду! - І вона чимдуж помчала до дверцят. Та ба! Дверцята знову виявилися замкнені, а ключик, як і перше, лежав на скляному столику.

"Кепські справи, кепські, далі нікуди, - подумала нещасна дитина. - Ніколи-ніколи я ще не була такою манюсінькою! І треба ж отаке лихо на мою голову!"

'That WAS a narrow escape!' said Alice, a good deal frightened at the sudden change, but very glad to find herself still in existence; 'and now for the garden!' and she ran with all speed back to the little door: but, alas! the little door was shut again, and the little golden key was lying on the glass table as before, 'and things are worse than ever,' thought the poor child, 'for I never was so small as this before, never! And I declare it's too bad, that it is!'

На останньому слові вона посковзнулася і - шубовсть! - по шию опинилася в солоній воді. Спочатку вона подумала, що якимось дивом упала в море.

- А коли так, - сказала вона собі, - то додому я повернуся залізницею.

(Аліса тільки раз у житті побувала біля моря і дійшла загального висновку, що там усюди є купальні кабінки*, дітлахи, що длубаються в піску дерев'яними лопатками, вишикувані в рядок готелі, а за ними - залізнична станція.) Проте вона хутко здогадалася, що плаває в озері сліз, яке сама наплакала ще бувши велеткою.

As she said these words her foot slipped, and in another moment, splash! she was up to her chin in salt water. Her first idea was that she had somehow fallen into the sea, 'and in that case I can go back by railway,' she said to herself. (Alice had been to the seaside once in her life, and had come to the general conclusion, that wherever you go to on the English coast you find a number of bathing machines in the sea, some children digging in the sand with wooden spades, then a row of lodging houses, and behind them a railway station.) However, she soon made out that she was in the pool of tears which she had wept when she was nine feet high.

- І чого було аж так ридати? - бідкалася Аліса, плаваючи туди-сюди в пошуках берега. - За те мені й кара!.. Ще потону у власних сльозах! Ото була б дивина! Щоправда, сьогодні - все дивина.

'I wish I hadn't cried so much!' said Alice, as she swam about, trying to find her way out. 'I shall be punished for it now, I suppose, by being drowned in my own tears! That WILL be a queer thing, to be sure! However, everything is queer to-day.'

Тут Аліса почула, як поблизу неї хтось хлюпочеться, і попливла на хлюпіт, аби з'ясувати, хто це. Спершу вона подумала, ніби то морж чи гіпопотам, але, згадавши, яка вона тепер маленька, зрозуміла, що то - звичайна миша, яка теж звалилась у воду.

Just then she heard something splashing about in the pool a little way off, and she swam nearer to make out what it was: at first she thought it must be a walrus or hippopotamus, but then she remembered how small she was now, and she soon made out that it was only a mouse that had slipped in like herself.

- Чи є зараз якийсь сенс, - подумала Аліса, - заходити в балачку з цією мишею? Тут усе таке незвичайне, що балакати вона напевно вміє... Та, зрештою, треба спробувати.

І вона звернулася до неї:

- О, Мишо, чи не знаєте ви, де тут берег? Я вже дуже стомилася плавати, о, Мишо!

Аліса вирішила, що до мишей слід звертатися саме так. Правда, досі подібної нагоди їй не випадало, але колись у братовому підручнику з граматики вона бачила табличку відмінювання:

Наз. миша Род. миші Дав. миші Знах. мишу Оруд. мишею Місц. на миші Клич. мишо!

Миша пильно глянула на Алісу й немовби підморгнула їй крихітним очком, але не озвалася й словом.

'Would it be of any use, now,' thought Alice, 'to speak to this mouse? Everything is so out-of-the-way down here, that I should think very likely it can talk: at any rate, there's no harm in trying.' So she began: 'O Mouse, do you know the way out of this pool? I am very tired of swimming about here, O Mouse!' (Alice thought this must be the right way of speaking to a mouse: she had never done such a thing before, but she remembered having seen in her brother's Latin Grammar, 'A mouse—of a mouse—to a mouse—a mouse—O mouse!') The Mouse looked at her rather inquisitively, and seemed to her to wink with one of its little eyes, but it said nothing.

"Може, вона не тямить по-нашому? - подумала Аліса. - Може, це французька миша, що припливла з Вільгельмом Завойовником?" (Треба сказати, що попри всю свою обізнаність з історії, Аліса трохи плуталася в давності подій.)

- Ou est ma chatte? - заговорила вона знову, згадавши найперше речення зі свого підручника французької мови.

Миша мало не вискочила з води і, здавалося, вся затремтіла з жаху.

- Перепрошую! - зойкнула Аліса, відчувши, що скривдила бідолашне звірятко. - Я зовсім забула, що ви недолюблюєте котів.

'Perhaps it doesn't understand English,' thought Alice; 'I daresay it's a French mouse, come over with William the Conqueror.' (For, with all her knowledge of history, Alice had no very clear notion how long ago anything had happened.) So she began again: 'Ou est ma chatte?' which was the first sentence in her French lesson-book. The Mouse gave a sudden leap out of the water, and seemed to quiver all over with fright. 'Oh, I beg your pardon!' cried Alice hastily, afraid that she had hurt the poor animal's feelings. 'I quite forgot you didn't like cats.'

- Недолюблюю котів?! - вереснула Миша. - А ти б їх долюблювала на моєму місці?!

'Not like cats!' cried the Mouse, in a shrill, passionate voice. 'Would YOU like cats if you were me?'

- Мабуть, що ні, - примирливо відказала Аліса. - Тільки не гнівайтесь... А все ж таки жаль, що я не можу показати вам нашу Діну. Ви б лише глянули - і одразу б закохалися в котів. Діна така мила і спокійна, - гомоніла Аліса чи то до Миші, чи то до себе, ліниво плаваючи в солоній воді, - сидить собі біля каміна і так солодко муркоче, лиже лапки і вмивається... А що вже пухнаста - так і кортить її погладити! А бачили б ви, як вона хвацько ловить мишей... Ой, вибачте, вибачте!.. - знову зойкнула Аліса, бо цього разу Миша вся наїжачилась, і Аліса збагнула, що образила її до глибини душі.

- Ми більше не говоритимем про це, якщо вам не до вподоби.

'Well, perhaps not,' said Alice in a soothing tone: 'don't be angry about it. And yet I wish I could show you our cat Dinah: I think you'd take a fancy to cats if you could only see her. She is such a dear quiet thing,' Alice went on, half to herself, as she swam lazily about in the pool, 'and she sits purring so nicely by the fire, licking her paws and washing her face—and she is such a nice soft thing to nurse—and she's such a capital one for catching mice—oh, I beg your pardon!' cried Alice again, for this time the Mouse was bristling all over, and she felt certain it must be really offended. 'We won't talk about her any more if you'd rather not.'

- Ми?! Ми не говоритимем!.. - заверещала Миша, тремтячи усім тілом аж до кінчика хвоста. - Начебто я говорила про таке!.. Наш рід споконвіку ненавидить котів - огидні, ниці, вульгарні створіння! Чути про них не хочу!

'We indeed!' cried the Mouse, who was trembling down to the end of his tail. 'As if I would talk on such a subject! Our family always HATED cats: nasty, low, vulgar things! Don't let me hear the name again!'

- Я більше не буду! - промовила Аліса і поквапилася змінити тему. - А чи любите ви со... собак?

Миша мовчала, й Аліса палко повела далі:

- Знали б ви, який милий песик живе з нами в сусідстві! Тер'єрчик - очка блискучі, шерсточка довга-предовга, руда й кучерява! Він уміє всілякі штучки: приносить, що кинуть, служить на задніх лапках - всього й не пригадаєш! А господар його, фермер, каже, що цьому песикові ціни нема, бо він, каже, вигублює до ноги всіх довколишніх щурів... 0-о-ой! - розпачливо зойкнула Аліса. - Я знов її образила!

І справді, Миша щодуху пливла геть, женучи озером рясні жмури.

'I won't indeed!' said Alice, in a great hurry to change the subject of conversation. 'Are you—are you fond—of—of dogs?' The Mouse did not answer, so Alice went on eagerly: 'There is such a nice little dog near our house I should like to show you! A little bright-eyed terrier, you know, with oh, such long curly brown hair! And it'll fetch things when you throw them, and it'll sit up and beg for its dinner, and all sorts of things—I can't remember half of them—and it belongs to a farmer, you know, and he says it's so useful, it's worth a hundred pounds! He says it kills all the rats and—oh dear!' cried Alice in a sorrowful tone, 'I'm afraid I've offended it again!' For the Mouse was swimming away from her as hard as it could go, and making quite a commotion in the pool as it went.

- Мишечко! шкряботушечко! - лагідно погукала Аліса. - Верніться, прошу вас! Ми вже не будемо говорити ні про котів, ні про собак, якщо вони вам такі немилі!

Зачувши ці слова, Миша розвернулася і поволеньки попливла назад: обличчя в неї було бліде ("від гніву!" - вирішила Аліса), а голос - тихий і тремкий.

- Ось вийдемо на берег, - мовила Миша, - і я розкажу тобі свою історію. Тоді ти зрозумієш, чому я так ненавиджу котів та собак.

So she called softly after it, 'Mouse dear! Do come back again, and we won't talk about cats or dogs either, if you don't like them!' When the Mouse heard this, it turned round and swam slowly back to her: its face was quite pale (with passion, Alice thought), and it said in a low trembling voice, 'Let us get to the shore, and then I'll tell you my history, and you'll understand why it is I hate cats and dogs.'

А виходити був саме час, бо в озерце набилося чимало птахів та звірів. Були тут і такий собі Качур, і Додо, і Папужка Лорі, й Орлятко, і ще якісь химерні істоти. І вся ця компанія на чолі з Алісою потягла на берег.

It was high time to go, for the pool was getting quite crowded with the birds and animals that had fallen into it: there were a Duck and a Dodo, a Lory and an Eaglet, and several other curious creatures. Alice led the way, and the whole party swam to the shore.

Audio from LibreVox.org