Alice's Adventures in Wonderland

CHAPTER II.

2

The Pool of Tears

JEZERO SLZ

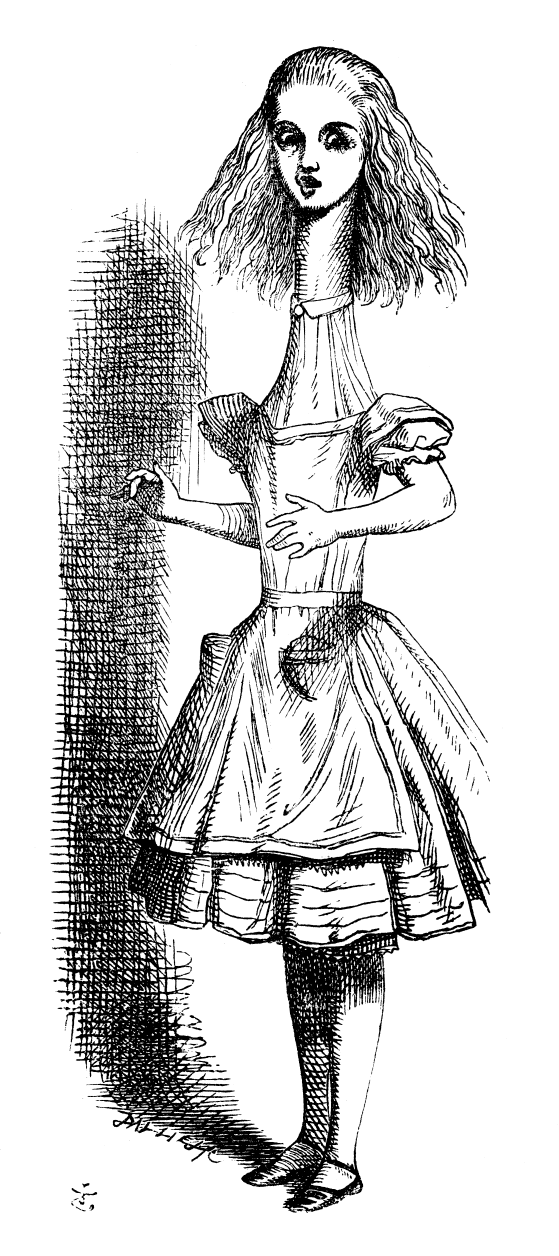

'Curiouser and curiouser!' cried Alice (she was so much surprised, that for the moment she quite forgot how to speak good English); 'now I'm opening out like the largest telescope that ever was! Good-bye, feet!' (for when she looked down at her feet, they seemed to be almost out of sight, they were getting so far off). 'Oh, my poor little feet, I wonder who will put on your shoes and stockings for you now, dears? I'm sure I shan't be able! I shall be a great deal too far off to trouble myself about you: you must manage the best way you can;—but I must be kind to them,' thought Alice, 'or perhaps they won't walk the way I want to go! Let me see: I'll give them a new pair of boots every Christmas.'

"Divoucnější a divoucnější!" zvolala Alenka (byla tak překvapena, že na okamžik zapomněla správně česky); "teďse vytahuji jako největší dalekohled, který kdo kdy viděl! Sbohem, nohy!" (Neboťkdyž se podívala dolůna své nohy, zdály se jí skoro unikat z dohledu, tak se jí vzdalovaly od hlavy.) "Ómé ubohé nohy, kdopak vám teďbude natahovat punčochy a obouvat boty, drahouškové? Já už jistěnebudu moci! Budu od vás příliš daleko, abych se o vás mohla starat; tak si to budete musit zařídit, jak nejlépe dovedete. "Ale musím na ně, být hodná," pomyslila si, "nebo by možná nechtěly chodit kam bych chtěla. Počkejme: každé Vánoce jim dám nový pár botek."

And she went on planning to herself how she would manage it. 'They must go by the carrier,' she thought; 'and how funny it'll seem, sending presents to one's own feet! And how odd the directions will look!

A začala uvažovat, jak by to zařídila. "Budou muset jít poslíčkem," pomyslila si; "to bude legračněvypadat, posílat dárky vlastním nohám! A jak podivněbude vypadat adresa!

ALICE'S RIGHT FOOT, ESQ.

HEARTHRUG,

NEAR THE FENDER,

(WITH ALICE'S LOVE).

Slovutná Alenčina Pravá Noha,

Koberec,

poblíž Stolu

(s Alenčinými pozdravy).

Oh dear, what nonsense I'm talking!'

Bože můj, jaké to mluvím nesmysly!"

Just then her head struck against the roof of the hall: in fact she was now more than nine feet high, and she at once took up the little golden key and hurried off to the garden door.

Vtom vrazila hlavou do stropu síně: vskutku byla už asi devět stop vysoká. Bez otálení vzala se stolku zlatý klíček a spěchala k zahradním dvířkám.

Poor Alice! It was as much as she could do, lying down on one side, to look through into the garden with one eye; but to get through was more hopeless than ever: she sat down and began to cry again.

Ubohá Alenka! Vše, co mohla udělat, bylo lehnout si na bok a dívat se do zahrady jedním okem; dostat se dvířky bylo beznadějnější než kdy jindy, a Alenka si sedla a dala se znovu do pláče.

'You ought to be ashamed of yourself,' said Alice, 'a great girl like you,' (she might well say this), 'to go on crying in this way! Stop this moment, I tell you!' But she went on all the same, shedding gallons of tears, until there was a large pool all round her, about four inches deep and reaching half down the hall.

"Mohla byste se stydět," řekla si po chvíli, "taková velká holka," (to mohla po pravdě říci) "a takhle brečet! Tu chvíli aťmi přestanete - no, co jsem řekla!" Ale plakala dál, roníc vědra a vědra slz, až kolem ní byla velká louže, asi čtyři palce hluboká a pokrývající celou polovinu síně.

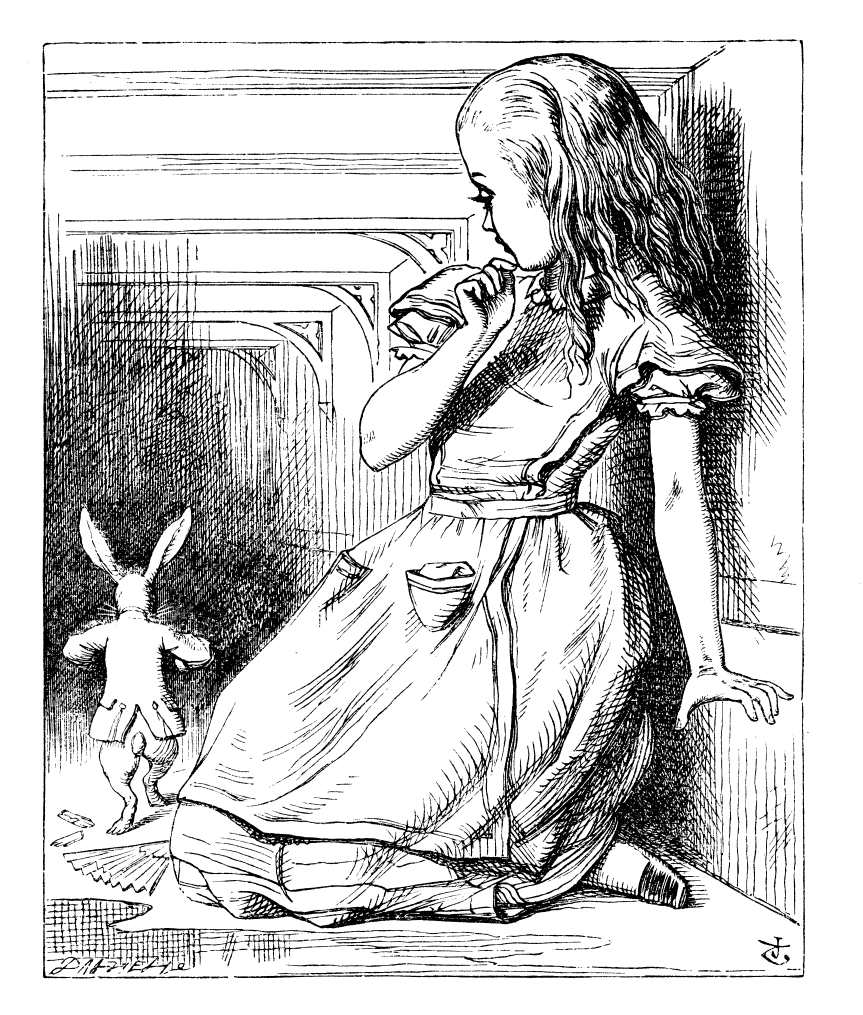

After a time she heard a little pattering of feet in the distance, and she hastily dried her eyes to see what was coming. It was the White Rabbit returning, splendidly dressed, with a pair of white kid gloves in one hand and a large fan in the other: he came trotting along in a great hurry, muttering to himself as he came, 'Oh! the Duchess, the Duchess! Oh! won't she be savage if I've kept her waiting!' Alice felt so desperate that she was ready to ask help of any one; so, when the Rabbit came near her, she began, in a low, timid voice, 'If you please, sir—' The Rabbit started violently, dropped the white kid gloves and the fan, and skurried away into the darkness as hard as he could go.

Po chvíli zaslechla v dálce lehké cupitání a spěšněsi osušila oči, aby viděla, kdo přichází. Byl to Bílý Králík, který se vracel nádherněoblečen a držel v jedné ruce pár bílých rukaviček a ve druhé velký vějíř. Cupital kolem ve velkém spěchu, bruče si k sobě: "O, vévodkyně! Ó, vévodkyně! Ta bude divá, že jsem ji nechal tak dlouho čekat!" Alenky se zmocňovala taková zoufalost, že byla odhodlána obrátit se o pomoc na kohokoli; když se tedy Králík přiblížil, začala tichým, nesmělým hláskem: "Prosím, pane..." Králík sebou prudce trhl, upustil vějířa bílé rukavice a odpelášil do temna, jak jen rychle dovedl.

Alice took up the fan and gloves, and, as the hall was very hot, she kept fanning herself all the time she went on talking: 'Dear, dear! How queer everything is to-day! And yesterday things went on just as usual. I wonder if I've been changed in the night? Let me think: was I the same when I got up this morning? I almost think I can remember feeling a little different. But if I'm not the same, the next question is, Who in the world am I? Ah, THAT'S the great puzzle!' And she began thinking over all the children she knew that were of the same age as herself, to see if she could have been changed for any of them.

Alenka zvedla vějířa rukavice, a jelikož bylo v síni velmi horko, začala se ovívati, neustávajíc v mluvení: "Bože, Bože, jak je to dnes všechno podivné! A včera š1o všechno docela jako jindy. Což jsem se přes noc změnila? Počkejme: byla jsem táž jako včera, když jsem se dnes ráno probudila? Skoro si vzpomínám, že jsem se necítila ve své kůži. Nejsem-li však táž jako včera, musím se ptát, kdo u všech všudy jsem? Aha, to je ta velká hádanka!" A začala probírat všechny známé děti, které s ní byly stejného věku, aby viděla, nezměnila-li se v některé z nich.

'I'm sure I'm not Ada,' she said, 'for her hair goes in such long ringlets, and mine doesn't go in ringlets at all; and I'm sure I can't be Mabel, for I know all sorts of things, and she, oh! she knows such a very little! Besides, SHE'S she, and I'm I, and—oh dear, how puzzling it all is! I'll try if I know all the things I used to know. Let me see: four times five is twelve, and four times six is thirteen, and four times seven is—oh dear! I shall never get to twenty at that rate! However, the Multiplication Table doesn't signify: let's try Geography. London is the capital of Paris, and Paris is the capital of Rome, and Rome—no, THAT'S all wrong, I'm certain! I must have been changed for Mabel! I'll try and say "How doth the little—"' and she crossed her hands on her lap as if she were saying lessons, and began to repeat it, but her voice sounded hoarse and strange, and the words did not come the same as they used to do:—

"Jistěnejsem Anča," řekla si, "protože ta má dlouhé kudrnaté vlasy, a mněse vlasy nekudrnatí, kdybych dělala co dělala; a jistěnemohu být Mařka, protože umím spoustu věcí, a Mařka - oh, ta toho umí tak málo! A mimo to, ona je ona, a já jsem já, a - bože můj, jak je to všechno zmatené! Musím zkusit, umím-li všechny věci, které jsem umívala. Počkejme: čtyřikrát pět je dvanáct, a čtyřikrát šest je třináct, a čtyřikrát sedm je - -ó, božínku! Takhle bych se nikdy nedostala k dvaceti! Ale konečně, násobilka nic neznamená: zkusme zeměpis. Praha je hlav ní město Vídně, Vídeňje hlavní město Paříže, a Paříž... Ne, to je všechno špatně, úplněšpatně! Musila jsem se proměnit v Mařku! Musím zkusit nějakou básničku, třeba: Běžel zajíc..." Postavila se způsobně, složila ruce v klín, jako kdyby stála ve škole a odříkávala úlohu, a začala deklamovat; ale její hlas zněl drsněa cize, a slova básničky, která jí přicházela na jazyk, nebyla také táž jako obyčejně:

'How doth the little crocodile

Improve his shining tail,

And pour the waters of the Nile

On every golden scale!

"Běžel zajíc kolem plotu,

roztrhal si v hrdle notu.

Kantor mu ji zašít spěchal,

v hrdle mu však jehlu nechal.

Zajíci teďskřípá nota

jako kantorova bota."

'How cheerfully he seems to grin,

How neatly spread his claws,

And welcome little fishes in

With gently smiling jaws!'

'I'm sure those are not the right words,' said poor Alice, and her eyes filled with tears again as she went on, 'I must be Mabel after all, and I shall have to go and live in that poky little house, and have next to no toys to play with, and oh! ever so many lessons to learn! No, I've made up my mind about it; if I'm Mabel, I'll stay down here! It'll be no use their putting their heads down and saying "Come up again, dear!" I shall only look up and say "Who am I then? Tell me that first, and then, if I like being that person, I'll come up: if not, I'll stay down here till I'm somebody else"—but, oh dear!' cried Alice, with a sudden burst of tears, 'I do wish they WOULD put their heads down! I am so VERY tired of being all alone here!'

"Ne, tohle jistěnejsou správná slova," řekla ubohá Alenka, a oči se jí znovu zalily slzami, jak pokračovala: "To už jsem jistěMařka, a budu muset jíst a bydlet v tom ošklivém malém domku, a nebudu mít skoro žádných hraček, a ó! tolik věcí se budu muset učit! Ne, v téhle věci jsem se rozhodla: jestliže jsem Mařka, zůstanu zde dole! Nic jim to nebude platno strkat sem hlavy a říkat: ,Drahoušku, pojďk nám sem nahoru!` Podívám se jenom vzhůru a řeknu: ,Kdo tedy jsem? To mi řekněte napřed, a teprve jestliže se mi bude líbit být tou osobou, vyjdu ven; jestliže ne, zůstanu zde dole, dokud nebudu někým jiným` -- ale, ó božínku!" zvolala v náhlém přívalu slzí, "kéž by sem někdo jen chtěl strčit hlavu! Mne už to tak mrzí být tu samotna!"

As she said this she looked down at her hands, and was surprised to see that she had put on one of the Rabbit's little white kid gloves while she was talking. 'How CAN I have done that?' she thought. 'I must be growing small again.' She got up and went to the table to measure herself by it, and found that, as nearly as she could guess, she was now about two feet high, and was going on shrinking rapidly: she soon found out that the cause of this was the fan she was holding, and she dropped it hastily, just in time to avoid shrinking away altogether.

Když to dořekla, podívala se dolůna své ruce a s úžasem zjistila, že si při té řeči natáhla jednu z Králíkových rukavic. "Jak sejen tohle mohlo stát?" pomyslila si. "To se zase musím zmenšovat." Vstala a šla ke stolu, aby se podle něj změřila, a shledala, že je, pokud mohla odhadnouti, asi dvěstopy vysoká a že se stále kvapem zmenšuje. Brzy přišla na to, že to zmenšování způsobil vějíř, který držela, i odhodila jej honem - zrovna včas, že unikla úplnému scvrknutí se v nic.

'That WAS a narrow escape!' said Alice, a good deal frightened at the sudden change, but very glad to find herself still in existence; 'and now for the garden!' and she ran with all speed back to the little door: but, alas! the little door was shut again, and the little golden key was lying on the glass table as before, 'and things are worse than ever,' thought the poor child, 'for I never was so small as this before, never! And I declare it's too bad, that it is!'

"To jsem ale šťastněvyvázla!" řekla si Alenka, hodně ulekaná náhlou změnou, ale šťastná, že se vidí ještěna světě. "A teďdo zahrady!" a běžela, jak nejrychleji dovedla, k malým dvířkám. Ale běda! dvířka byla opět zavřena a zlatý klíček ležel opět na skleněném stolku, "a to je horší, než to bylo," myslilo si ubohé dítě, "neboťjsem nikdy nebyla tak malá, jako jsem teď- nikdy! A to je na mou věru velmi, velmi zlé!"

As she said these words her foot slipped, and in another moment, splash! she was up to her chin in salt water. Her first idea was that she had somehow fallen into the sea, 'and in that case I can go back by railway,' she said to herself. (Alice had been to the seaside once in her life, and had come to the general conclusion, that wherever you go to on the English coast you find a number of bathing machines in the sea, some children digging in the sand with wooden spades, then a row of lodging houses, and behind them a railway station.) However, she soon made out that she was in the pool of tears which she had wept when she was nine feet high.

Jak vyřkla tato slova, uklouzla jí noha, a v mžiku, plác! byla po krk ve slané vodě. První, co jí napadlo, bylo, že nějak spadla do moře, "a v tom případěse vrátím domůvlakem," řekla si k sobě. (Alenka byla jednou s rodiči u moře a její představa mořského břehu od té doby byla řada kabin na svlékání, děti, hrabající v písku dřevěnými lopatkami, vzadu řada domůa za nimi železniční stanice.) Brzy však přišla na to, že se octla ve velké louži slz, které naplakala, když byla devět stop vysoká.

'I wish I hadn't cried so much!' said Alice, as she swam about, trying to find her way out. 'I shall be punished for it now, I suppose, by being drowned in my own tears! That WILL be a queer thing, to be sure! However, everything is queer to-day.'

"Kéž bych byla tolik neplakala!" řekla Alenka, plavajíc v louži a hledajíc, jak by se z ní dostala ven. "Teďza to budu, myslím, potrestána tím, že se utopím ve vlastních slzách! Bude to podivné - ale všechno je dnes tak podivné..."

Just then she heard something splashing about in the pool a little way off, and she swam nearer to make out what it was: at first she thought it must be a walrus or hippopotamus, but then she remembered how small she was now, and she soon made out that it was only a mouse that had slipped in like herself.

Vtom zaslechla opodál jakési šplouchání a plavala tím směrem, aby se přesvědčila, co to je: nejprve se domnívala, že to je jistěnějaký mrož nebo nosorožec, pak se však upamatovala, jak je teďmaličká, a brzy rozpoznala, že je to jen myš, která do louže sklouzla asi stejnějako ona.

'Would it be of any use, now,' thought Alice, 'to speak to this mouse? Everything is so out-of-the-way down here, that I should think very likely it can talk: at any rate, there's no harm in trying.' So she began: 'O Mouse, do you know the way out of this pool? I am very tired of swimming about here, O Mouse!' (Alice thought this must be the right way of speaking to a mouse: she had never done such a thing before, but she remembered having seen in her brother's Latin Grammar, 'A mouse—of a mouse—to a mouse—a mouse—O mouse!') The Mouse looked at her rather inquisitively, and seemed to her to wink with one of its little eyes, but it said nothing.

"Bude mi co platno k téhle myši promluvit?" pomyslila si Alenka. "Všechno je tu dole tak neobyčejné, že si myslím, že i myš bude mluvit; rozhodněvšak za pokus tostojí." Tak začala: "Ó Myško, neznáte cestu z tohoto jezera? Jsem už velmi unavena plaváním, ó Myško!" (Alenka se domnívala, že tohle je správný způsob, jak oslovit myš: nikdy předtím k myši nemluvila, vzpomněla si však, že viděla v bratrovělatinské gramatice: "Žába - žáby - žábě- žábu - ó žábo!") Myš se nani podívala jaksi zpytavěa neříkala nic; Alence se však zdálo, že na ni mrkla jedním očkem.

'Perhaps it doesn't understand English,' thought Alice; 'I daresay it's a French mouse, come over with William the Conqueror.' (For, with all her knowledge of history, Alice had no very clear notion how long ago anything had happened.) So she began again: 'Ou est ma chatte?' which was the first sentence in her French lesson-book. The Mouse gave a sudden leap out of the water, and seemed to quiver all over with fright. 'Oh, I beg your pardon!' cried Alice hastily, afraid that she had hurt the poor animal's feelings. 'I quite forgot you didn't like cats.'

"Možná že nerozumí česky," pomyslila si Alenka; "to bude, počítám, německá myš, která sem přišla s Jindřichem Ptáčníkem." (Vidíte, že se vší svou znalostí historie Alenka neměla jasné představy, jak dávno se co stalo.) Začala tedy znovu: "Wo ist meine Katze?", což byla první věta v její německé čítance. Myš prudce vyskočila z louže a Alence se zdálo, že se třese po celém těle hrůzou. "Ó, prosím za odpuštění!" zvolala spěšně, plna strachu, že se dotkla citů ubohého zvířátka. "Zapomněla jsem, že nemáte ráda koček."

'Not like cats!' cried the Mouse, in a shrill, passionate voice. 'Would YOU like cats if you were me?'

"Nemám ráda koček!" zapískla Myš rozčileně. "Měla byste vy ráda kočky, kdybyste byla mnou?"

'Well, perhaps not,' said Alice in a soothing tone: 'don't be angry about it. And yet I wish I could show you our cat Dinah: I think you'd take a fancy to cats if you could only see her. She is such a dear quiet thing,' Alice went on, half to herself, as she swam lazily about in the pool, 'and she sits purring so nicely by the fire, licking her paws and washing her face—and she is such a nice soft thing to nurse—and she's such a capital one for catching mice—oh, I beg your pardon!' cried Alice again, for this time the Mouse was bristling all over, and she felt certain it must be really offended. 'We won't talk about her any more if you'd rather not.'

"Nu, možná že ne," řekla Alenka chlácholivě, "ale už se proto nehněvejte. -A přece bych si přála, abych vám mohla ukázat naši Mindu: myslím, že byste si zamilovala kočky, kdybyste ji viděla. To je vám takové mírné, drahé zvířátko," pokračovala Alenka, polo k myši a polo k sobě, plovajíc v louži, "a tak pěkněsedí u krbu a přede a olizuje si pacičky a umývá se - a je tak teploučká a měkoučká na chování - a tak ohromně dovede chytat myši - ó, prosím za odpuštění!" zvolala znovu, neboťtentokrát byla Myš celá zježená a Alenkacítila, že musí být doopravdy uražena. "Nebudeme o ní dál mluvit, nemáte-li to ráda."

'We indeed!' cried the Mouse, who was trembling down to the end of his tail. 'As if I would talk on such a subject! Our family always HATED cats: nasty, low, vulgar things! Don't let me hear the name again!'

"Nebudeme - - vskutku!" křičela Myš, která se třásla od hlavy po ocas. "Jako kdybych já kdy mluvila o takovém předmětě! Naše rodina vždycky nenáviděla kočky: ošklivé, sprosté, nízké tvory! Aťuž to jméno neslyším!"

'I won't indeed!' said Alice, in a great hurry to change the subject of conversation. 'Are you—are you fond—of—of dogs?' The Mouse did not answer, so Alice went on eagerly: 'There is such a nice little dog near our house I should like to show you! A little bright-eyed terrier, you know, with oh, such long curly brown hair! And it'll fetch things when you throw them, and it'll sit up and beg for its dinner, and all sorts of things—I can't remember half of them—and it belongs to a farmer, you know, and he says it's so useful, it's worth a hundred pounds! He says it kills all the rats and—oh dear!' cried Alice in a sorrowful tone, 'I'm afraid I've offended it again!' For the Mouse was swimming away from her as hard as it could go, and making quite a commotion in the pool as it went.

"Už ho nevyslovím, opravdu!" řekla Alenka, pospíchajíc změnit předmět rozmluvy. "Máte - máte ráda -- máte ráda - psy?" Myš neodpověděla, Alenka tedy dychtivěpokračovala: "U našich sousedůmají takového pěkného pejska, toho bych vám chtěla ukázat. Je to malý jezevčík a má taková chytrá očka, víte, a takovou dlouhou vlnivou hnědou srst! A donáší věci, které mu hodíte, a dovede se postavit a prosit o jídlo, a všechno možné dovede: - ani si to všechno nemohu vzpomenout- a patří zahradníkovi, víte, a ten říká, že je tak užitečný, a stojí za tisíce! A říká, že mu už pochytal všechny krysy, a - - oh, jemináčku!" zvolala Alenka lítostivým hlasem, "už jsem ji zase urazila!" NeboťMyš plavala pryč, jak nejrychleji dovedla, způsobujíc v louži úplné vlnobití.

So she called softly after it, 'Mouse dear! Do come back again, and we won't talk about cats or dogs either, if you don't like them!' When the Mouse heard this, it turned round and swam slowly back to her: its face was quite pale (with passion, Alice thought), and it said in a low trembling voice, 'Let us get to the shore, and then I'll tell you my history, and you'll understand why it is I hate cats and dogs.'

Alenka na ni tedy zavolala konejšivě: "Myško, drahá! Vraťte se, drahoušku, a nebudeme už mluvit o kočkách ani o psech, nemáte-li jich ráda!" Kdyžto Myš uslyšela, obrátila se a zvolna plavala zpět: byla ve tváři úplněbledá (hněvem, pomyslila si Alenka) a řekla hlubokým, chvějícím se hlasem: "Pojďme na břeh a já vám povím příběh svého života a porozumíte, proč nenávidím kočky a psy."

It was high time to go, for the pool was getting quite crowded with the birds and animals that had fallen into it: there were a Duck and a Dodo, a Lory and an Eaglet, and several other curious creatures. Alice led the way, and the whole party swam to the shore.

Byl nejvyšší čas, neboťlouže začínala být pomalu přeplněna zvířaty a ptáky, kteří do ní spadli: byla mezi nimi kachna a papoušek Lora, dokonce jeden Blboun, kterému říkali Dodo, orlík a několik jiných podivných stvoření. Alenka vedla a celá společnost plavala ke břehu.

Audio from LibreVox.org