Alice's Adventures in Wonderland

CHAPTER III.

III

A Caucus-Race and a Long Tale

Een verkiezings-wedstrijd en een treurig verhaal

They were indeed a queer-looking party that assembled on the bank—the birds with draggled feathers, the animals with their fur clinging close to them, and all dripping wet, cross, and uncomfortable.

HET was werkelijk een zonderling gezelschap, dat daar aan de kant bij elkaar kwam - de vogels met beslijkte veren, de andere dieren met een vastgeplakte vacht en allemaal even kletsnat, knorrig en slecht op hun gemak.

The first question of course was, how to get dry again: they had a consultation about this, and after a few minutes it seemed quite natural to Alice to find herself talking familiarly with them, as if she had known them all her life. Indeed, she had quite a long argument with the Lory, who at last turned sulky, and would only say, 'I am older than you, and must know better'; and this Alice would not allow without knowing how old it was, and, as the Lory positively refused to tell its age, there was no more to be said.

In de eerste plaats moesten ze natuurlijk zien droog te worden; ze gingen daarover beraadslagen en al gauw vond Alice het heel gewoon, dat zij met hen praatte, of zij hen haar hele leven al kende. Zij had dan ook een lang gesprek met de Papegaai, die op het laatste boos werd en enkel zei: ‘Ik ben ouder dan jij en weet het dus beter’; en Alice wilde dat niet aannemen voor zij wist hoe oud hij was, maar toen de Papegaai dat absoluut niet wou vertellen, was er verder weinig meer te bespreken.

At last the Mouse, who seemed to be a person of authority among them, called out, 'Sit down, all of you, and listen to me! I'LL soon make you dry enough!' They all sat down at once, in a large ring, with the Mouse in the middle. Alice kept her eyes anxiously fixed on it, for she felt sure she would catch a bad cold if she did not get dry very soon.

Tenslotte riep de Muis, die blijkbaar een persoon van gewicht onder hen was: ‘Ga allemaal zitten en luister naar mij! Ik zal jullie wel droogmaken.’ Ze gingen meteen allemaal in een grote kring zitten met de Muis in het midden. Alice keek hem bezorgd en gespannen aan, want zij wist zeker, dat zij lelijk kou zou vatten als zij niet gauw droog werd.

'Ahem!' said the Mouse with an important air, 'are you all ready? This is the driest thing I know. Silence all round, if you please! "William the Conqueror, whose cause was favoured by the pope, was soon submitted to by the English, who wanted leaders, and had been of late much accustomed to usurpation and conquest. Edwin and Morcar, the earls of Mercia and Northumbria—"'

‘Ehum’, zei de Muis gewichtig, ‘zijn jullie klaar? Ik zal jullie het droogste vertellen dat ik weet. Stilte alsjeblieft! In 1648 werd te Munster vrede met Spanje gesloten; Spanje verklaarde de Nederlanden onafhankelijk; de zeven Nederlanden waren: Holland, Zeeland, Utrecht, Overijssel, Friesland en Groningen; Drente mocht niet meestemmen; de Generaliteitslanden werden als veroverd gebied beschouwd.’

'Ugh!' said the Lory, with a shiver.

‘Br,’ zei de Papegaai rillend.

'I beg your pardon!' said the Mouse, frowning, but very politely: 'Did you speak?'

‘Pardon,’ zei de Muis, zijn voorhoofd fronsend, maar heel beleefd, ‘zei je iets?’

'Not I!' said the Lory hastily.

‘Ik niet,’ zei de Papegaai snel.

'I thought you did,' said the Mouse. '—I proceed. "Edwin and Morcar, the earls of Mercia and Northumbria, declared for him: and even Stigand, the patriotic archbishop of Canterbury, found it advisable—"'

‘O, dat dacht ik,’ zei de Muis, ‘ik ga verder. Frederik Hendrik, die in 1647 was gestorven, was opgevolgd door zijn zoon Willem II. Na de vrede werd een deel van het leger afgedankt, omdat men het niet meer nodig had; de Staten van Holland vonden het echter -’

'Found WHAT?' said the Duck.

‘Vonden wat?’ zei de Eend.

'Found IT,' the Mouse replied rather crossly: 'of course you know what "it" means.'

‘Vonden het’ antwoordde de Muis geërgerd, ‘je weet toch wel wat “het” betekent.’

'I know what "it" means well enough, when I find a thing,' said the Duck: 'it's generally a frog or a worm. The question is, what did the archbishop find?'

‘Zeker, dat weet ik heel goed, als ik iets vind’, zei de Eend, ‘dat is meestal een kikvors of een worm, maar nu is de vraag: wat vonden de Staten van Holland?’

The Mouse did not notice this question, but hurriedly went on, '"—found it advisable to go with Edgar Atheling to meet William and offer him the crown. William's conduct at first was moderate. But the insolence of his Normans—" How are you getting on now, my dear?' it continued, turning to Alice as it spoke.

De Muis ging hier verder niet op in, maar vervolgde snel: ‘vonden het echter beter om nog meer soldaten af te danken, daar zij wel de helft van alle onkosten droegen. Toen de Staten van Holland echter op eigen gezag een aantal soldaten afdankten, droegen de Staten-Generaal aan Willem II op... Hoe gaat het nu met je,’ vroeg hij eensklaps aan Alice.

'As wet as ever,' said Alice in a melancholy tone: 'it doesn't seem to dry me at all.'

‘Ik ben nog altijd even nat,’ zei Alice treurig, ‘ik word er blijkbaar helemaal niet droog van.’

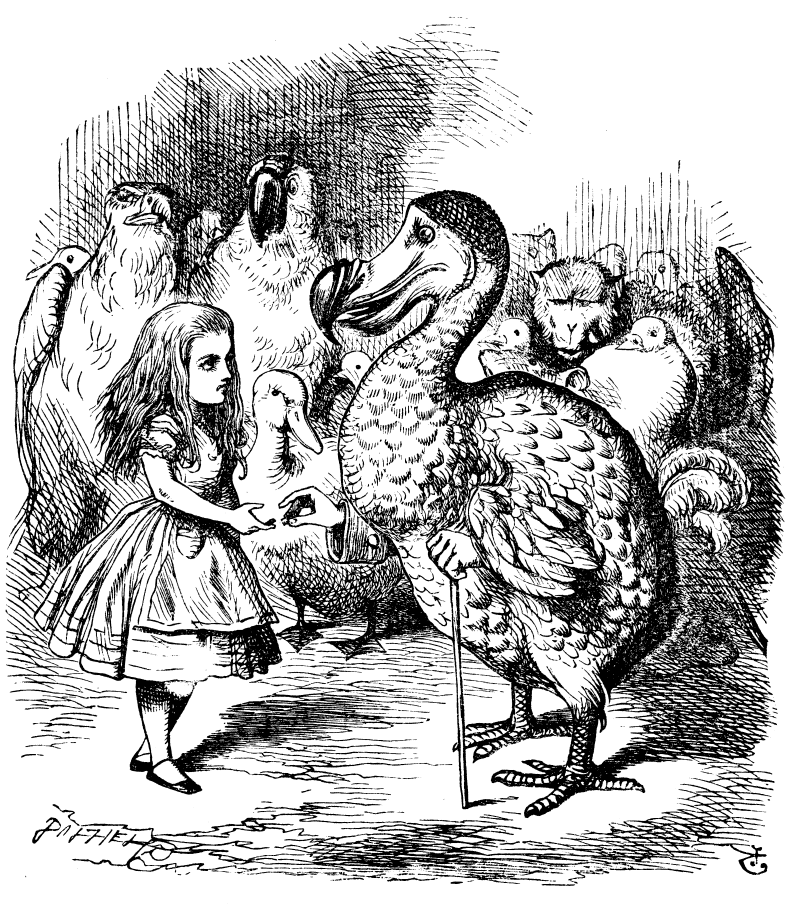

'In that case,' said the Dodo solemnly, rising to its feet, 'I move that the meeting adjourn, for the immediate adoption of more energetic remedies—'

‘In dat geval,’ zei de Dodo plechtig, ‘geef ik het advies de vergadering te verdagen, opdat het nemen van doeltreffender middelen ten snelste bevorderd kan worden.’

'Speak English!' said the Eaglet. 'I don't know the meaning of half those long words, and, what's more, I don't believe you do either!' And the Eaglet bent down its head to hide a smile: some of the other birds tittered audibly.

‘Praat Nederlands,’ zei de Arend, ‘ik begrijp niets van al die lange woorden en jijzelf, geloof ik, evenmin.’ En de Arend boog zijn hoofd om een glimlach te verbergen; een paar van de andere vogels gichelden duidelijk hoorbaar.

'What I was going to say,' said the Dodo in an offended tone, 'was, that the best thing to get us dry would be a Caucus-race.'

‘Wat ik jullie wou zeggen’, zei de Dodo beledigd, ‘was dat het beste middel om droog te worden een verkiezings-wedstrijd is.’

'What IS a Caucus-race?' said Alice; not that she wanted much to know, but the Dodo had paused as if it thought that SOMEBODY ought to speak, and no one else seemed inclined to say anything.

‘Wat is een verkiezings-wedstrijd?’ vroeg Alice. Zij was daar niet zo erg nieuwsgierig naar, maar de Dodo zweeg even, alsof zij verwachtte dat iemand iets zeggen zou en geen van de anderen scheen daar behoefte aan te hebben.

'Why,' said the Dodo, 'the best way to explain it is to do it.' (And, as you might like to try the thing yourself, some winter day, I will tell you how the Dodo managed it.)

‘Ik kan je dat het beste verklaren,’ zei de Dodo, ‘wanneer wij beginnen.’ (En nu zal ik je vertellen hoe de Dodo het uitlegde, want je wilt het misschien op een regenachtige dag ook eens proberen).

First it marked out a race-course, in a sort of circle, ('the exact shape doesn't matter,' it said,) and then all the party were placed along the course, here and there. There was no 'One, two, three, and away,' but they began running when they liked, and left off when they liked, so that it was not easy to know when the race was over. However, when they had been running half an hour or so, and were quite dry again, the Dodo suddenly called out 'The race is over!' and they all crowded round it, panting, and asking, 'But who has won?'

Eerst tekende ze een renbaan in een soort cirkel (‘Het doet er niet toe of die goed is’ zei ze) en toen moest het hele gezelschap er zo hier en daar langs gaan staan. Het begon niet met ‘een, twee, drie, af,’ neen, ze gingen hollen als ze zin hadden en hielden dan weer op, als ze zin hadden, zodat het niet gemakkelijk was om er achter te komen, wanneer de wedstrijd uit was. Toen ze zo ongeveer een half uur heen en weer hadden gehold en droog waren geworden, riep de Dodo plotseling: ‘De wedstrijd is afgelopen’ en ze gingen allemaal hijgend om haar heen staan en vroegen ‘Wie heeft gewonnen?’

This question the Dodo could not answer without a great deal of thought, and it sat for a long time with one finger pressed upon its forehead (the position in which you usually see Shakespeare, in the pictures of him), while the rest waited in silence. At last the Dodo said, 'EVERYBODY has won, and all must have prizes.'

De Dodo moest eerst lang nadenken voor zij daarop kon antwoorden en zij zat een hele tijd met haar wijsvinger tegen haar voorhoofd te denken (in de houding waarin je dichters meestal op plaatjes ziet), terwijl de anderen zwijgend wachtten. Tenslotte zei de Dodo: ‘Iedereen heeft het gewonnen, jullie moet allemaal een prijs hebben.’

'But who is to give the prizes?' quite a chorus of voices asked.

‘Maar wie moet voor die prijzen zorgen?’ vroeg een koor van stemmen.

'Why, SHE, of course,' said the Dodo, pointing to Alice with one finger; and the whole party at once crowded round her, calling out in a confused way, 'Prizes! Prizes!'

‘Wel zij natuurlijk,’ zei de Dodo en wees met één vinger naar Alice; en het hele gezelschap ging om haar heen staan en ze riepen allemaal door elkaar heen: ‘Prijzen, kom op met je prijzen!’

Alice had no idea what to do, and in despair she put her hand in her pocket, and pulled out a box of comfits, (luckily the salt water had not got into it), and handed them round as prizes. There was exactly one a-piece all round.

Alice wist niet wat ze moest doen en wanhopig stak ze haar hand in haar zak en haalde er een doos zuurtjes uit (gelukkig had het zoute water die niet aangetast) en gaf ieder één als prijs.

'But she must have a prize herself, you know,' said the Mouse.

‘Maar ze moet zelf ook een prijs hebben,’ zei de Muis.

'Of course,' the Dodo replied very gravely. 'What else have you got in your pocket?' he went on, turning to Alice.

‘Natuurlijk,’ zei de Dodo heel ernstig. ‘Wat heb je verder nog in je zak?’ vroeg zij aan Alice en draaide zich naar haar om.

'Only a thimble,' said Alice sadly.

‘Enkel een vingerhoed,’ zei Alice bedroefd.

'Hand it over here,' said the Dodo.

‘Geef die hier,’ zei de Dodo.

Then they all crowded round her once more, while the Dodo solemnly presented the thimble, saying 'We beg your acceptance of this elegant thimble'; and, when it had finished this short speech, they all cheered.

Toen gingen ze weer om haar heen staan, terwijl de Dodo haar plechtig de vingerhoed aanbood en zei: ‘Wij verzoeken U beleefd deze sierlijke vingerhoed te willen aanvaarden’ en toen zij deze korte toespraak had uitgesproken, begonnen ze allen te klappen.

Alice thought the whole thing very absurd, but they all looked so grave that she did not dare to laugh; and, as she could not think of anything to say, she simply bowed, and took the thimble, looking as solemn as she could.

Alice vond het hele geval erg dwaas, maar ze keken zo ernstig dat ze niet dorst te lachen, en toen ze geen goed antwoord kon bedenken, boog ze alleen maar diep en deed haar prijs zo plechtig als ze kon aan haar vinger.

The next thing was to eat the comfits: this caused some noise and confusion, as the large birds complained that they could not taste theirs, and the small ones choked and had to be patted on the back. However, it was over at last, and they sat down again in a ring, and begged the Mouse to tell them something more.

Ze gingen nu hun zuurtjes op eten; dat veroorzaakte weer allerlei lawaai en verwarring, want de grote vogels klaagden dat zij er niets van proefden en de kleine verslikten zich er in en moesten op hun rug geklopt worden. Tenslotte waren ze allemaal klaar en ze gingen weer in een kring zitten en smeekten de Muis nog iets te vertellen.

'You promised to tell me your history, you know,' said Alice, 'and why it is you hate—C and D,' she added in a whisper, half afraid that it would be offended again.

‘U hebt me beloofd dat U me Uw geschiedenis zou vertellen,’ zei Alice ‘en waarom u K. en H. zo haat,’ voegde ze er fluisterend aan toe, bang dat hij weer beledigd zou zijn. En intussen keek ze in het rond en haar blik bleef lang rusten op de lange staart van de Muis, die in mooie bochten op de grond lag.

'Mine is a long and a sad tale!' said the Mouse, turning to Alice, and sighing.

‘Ach, die is lang en treurig’, zei de Muis zuchtend tot Alice.

'It IS a long tail, certainly,' said Alice, looking down with wonder at the Mouse's tail; 'but why do you call it sad?' And she kept on puzzling about it while the Mouse was speaking, so that her idea of the tale was something like this:—

‘'t Is een lange staart, zeker’, dacht Alice en ze keek er verwonderd naar, ‘maar waarom noemt hij hem treurig?’ En zij bleef daarover nadenken, terwijl de Muis vertelde, zodat in haar idee het verhaal er ongeveer zo uitzag:

'Fury said to a

mouse, That he

met in the

house,

"Let us

both go to

law: I will

prosecute

YOU.—Come,

I'll take no

denial; We

must have a

trial: For

really this

morning I've

nothing

to do."

Said the

mouse to the

cur, "Such

a trial,

dear Sir,

With

no jury

or judge,

would be

wasting

our

breath."

"I'll be

judge, I'll

be jury,"

Said

cunning

old Fury:

"I'll

try the

whole

cause,

and

condemn

you

to

death."'

Poes zei tot een

Muis, die hij

zag in

het huis:

‘Kom blijf

daar niet

staan, want

ik klaag je aan.

Je hoeft niets

te beweren,

wij moeten

procederen,

dan heb ik

vanmorgen mijn

tijd niet

verdaan.’

Zei de Muis

tot dat schoelje,

‘Mijnheer wat

bedoel

je, zonder

jury

of rechter

zal dat toch

niet gaan’.

‘Ik ben

rechter

en jury’,

zei ijskoud

die Furie,’ en

ik oordeel

bedaard:

de dood

door

het

zwaard

'You are not attending!' said the Mouse to Alice severely. 'What are you thinking of?'

‘Je let niet op,’ zei de Muis streng tot Alice, ‘waar denk je aan?’

'I beg your pardon,' said Alice very humbly: 'you had got to the fifth bend, I think?'

‘Neemt u me niet kwalijk,’ zei Alice erg nederig, ‘u was geloof ik aan de vijfde kronkel.’

'I had NOT!' cried the Mouse, sharply and very angrily.

'A knot!' said Alice, always ready to make herself useful, and looking anxiously about her. 'Oh, do let me help to undo it!'

'I shall do nothing of the sort,' said the Mouse, getting up and walking away. 'You insult me by talking such nonsense!'

‘Daar was ik helemaal niet,’ zei de Muis terwijl hij opstond en wegliep, ‘je beledigt me, wanneer je zulke onzin praat!’

'I didn't mean it!' pleaded poor Alice. 'But you're so easily offended, you know!'

‘Maar dat was de bedoeling toch niet,’ zei de arme Alice smekend, ‘jullie zijn ook zo gauw beledigd.’

The Mouse only growled in reply.

De Muis bromde maar wat als antwoord.

'Please come back and finish your story!' Alice called after it; and the others all joined in chorus, 'Yes, please do!' but the Mouse only shook its head impatiently, and walked a little quicker.

‘Ach komt u toch terug en vertel uw verhaal verder,’ riep Alice hem na. En de anderen riepen allemaal in koor: ‘Ja, alsjeblieft,’ maar de Muis schudde ongeduldig zijn hoofd en liep nog wat harder.

'What a pity it wouldn't stay!' sighed the Lory, as soon as it was quite out of sight; and an old Crab took the opportunity of saying to her daughter 'Ah, my dear! Let this be a lesson to you never to lose YOUR temper!' 'Hold your tongue, Ma!' said the young Crab, a little snappishly. 'You're enough to try the patience of an oyster!'

‘Wat jammer dat hij niet blijven wou,’ zuchtte de Papegaai toen hij uit het gezicht was en een oude Krab vond dit een goede gelegenheid om haar dochter te vermanen: ‘Zie je, kindje, leer hieruit dat je altijd je goede humeur moet bewaren.’ ‘Hou toch je mond Moeder,’ zei de jonge Krab een beetje snibbig, ‘van jou zou een oester nog zijn geduld verliezen.’

'I wish I had our Dinah here, I know I do!' said Alice aloud, addressing nobody in particular. 'She'd soon fetch it back!'

‘Ik wou dat onze Dina hier was,’ zei Alice hardop, zonder zich tot iemand persoonlijk te richten, ‘die zou hem wel gauw terugbrengen.’

'And who is Dinah, if I might venture to ask the question?' said the Lory.

‘En wie is Dina, als ik vragen mag,’ zei de Papegaai.

Alice replied eagerly, for she was always ready to talk about her pet: 'Dinah's our cat. And she's such a capital one for catching mice you can't think! And oh, I wish you could see her after the birds! Why, she'll eat a little bird as soon as look at it!'

Alice ging er gretig op in, want ze vond het altijd prettig om over haar lievelingsdier te praten. ‘Dina,’ zei ze ‘is onze kat. En ze kan zo geweldig muizen vangen, dat moest u eens zien. En u moest eens zien hoe ze achter een vogel aanzit. Als ze er naar kijkt, dan heeft ze hem ook.’

This speech caused a remarkable sensation among the party. Some of the birds hurried off at once: one old Magpie began wrapping itself up very carefully, remarking, 'I really must be getting home; the night-air doesn't suit my throat!' and a Canary called out in a trembling voice to its children, 'Come away, my dears! It's high time you were all in bed!' On various pretexts they all moved off, and Alice was soon left alone.

Dit gezegde bracht het gezelschap in grote opschudding. Sommige vogels renden meteen weg; een oude ekster begon zich zorgvuldig in een omslagdoek te wikkelen. ‘Nu moet ik heus gaan,’ zei ze, ‘de nachtlucht is zo slecht voor mijn keel’ en een kanarie riep met bevende stem tot haar kinderen: ‘Kom mee, lievelingen, 't is hoog tijd, dat jullie nu naar bed gaan.’ Zo gingen ze onder verschillende voorwendsels allemaal weg en Alice bleef heel alleen achter.

'I wish I hadn't mentioned Dinah!' she said to herself in a melancholy tone. 'Nobody seems to like her, down here, and I'm sure she's the best cat in the world! Oh, my dear Dinah! I wonder if I shall ever see you any more!' And here poor Alice began to cry again, for she felt very lonely and low-spirited. In a little while, however, she again heard a little pattering of footsteps in the distance, and she looked up eagerly, half hoping that the Mouse had changed his mind, and was coming back to finish his story.

‘Ik wou dat ik het niet over Dina had gehad,’ zei ze droevig bij zichzelf, ‘niemand schijnt hier beneden op haar gesteld te zijn en toch is het de beste kat van de wereld. O Dina, zal ik je nog ooit terugzien?’ En toen begon de arme Alice weer te huilen, want zij voelde zich zo alleen en zo neerslachtig. Maar na een poosje hoorde ze op een afstand weer getrippel van voeten en zij keek vlug op, want ze hoopte half dat de Muis van plan veranderd was en terug kwam om zijn verhaal verder te vertellen.

Audio from LibreVox.org